13.3: Glance at the Research Process- Key Skills

- Page ID

- 140043

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Locate and evaluate primary and secondary research materials, including journal articles and essays, books, scholarly and professionally established and maintained databases or archives, and informal electronic networks and Internet sources.

- Practice and apply strategies such as interpretation, synthesis, response, and critique to compose texts that integrate the writer’s ideas with those from appropriate sources.

- Apply methods and technologies commonly used for research and communication in various fields.

Your task in writing an argumentative research paper as outlined in Writing Process: Integrating Research is to present original thinking that is supported by researched evidence. You may wonder how a college student will think of anything new to say about a topic that already has been researched by many others. First, keep in mind that your original thinking does not necessarily have to be groundbreaking—something never considered by others in the field—though it might be. Your original thinking may be something smaller but equally important, such as offering an alternative viewpoint on some evidence, interpreting existing evidence in a new way that sheds light on current questions in the field, or pointing out a flaw in the current thinking regarding a topic.

Synthesis

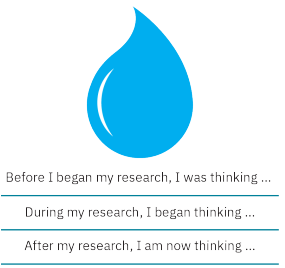

One skill that will help you develop this original thinking is synthesis. As explained in Writing Process: Integrating Research, synthesis involves combining information gathered from various sources and making connections among those sources to create a new, deeper, or changed understanding of a topic. In other words, you examine how information or opinions you have read in one place relate to what you have read in another place or to your own thoughts. To practice the skill of synthesis, use Figure \(13.6\), which illustrates how thinking can change like ripples of water.

Figure \(13.6\) Synthesizing research (CC BY 4.0; Rice University & OpenStax)

Keeping Track of Sources

Because unorganized or incorrectly documented research may be less than useless, many researchers make the effort to keep their notes and comments on their sources in a research log. An organized record of all sources consulted, a research log includes publication information, notes taken from the sources, and commentary about their relation to other sources or to the thesis of your paper. Having a dynamic tool such as this makes it easier to document sources in your works cited or references list and place in-text citations in your paper. It also helps with the research itself, showing at a glance what information you already have and where it comes from so that you can avoid repetition. Equally important, commentary on notes helps you synthesize information efficiently.

Key Research Skills

In addition to synthesis and research log maintenance, a good researcher needs the following skills to perform required tasks:

- Critical analysis: Ability to think about what text or data means and how the parts relate to the whole.

- Critical thinking: Ability to analyze, make inferences, evaluate, synthesize, and draw conclusions on the basis of researched information.

- Data collection: Ability to gather facts and research on a topic through various kinds of sources, field research, observation, interviews, surveys or questionnaires, experimentation, and/or focus groups.

- Field research: Ability to collect raw data outside a laboratory, library, or workplace setting; observation and data collection in the subject’s natural environment.

- Interviewing: Ability to engage in questions and answers with experts or those who have knowledge to share regarding a research topic.

- Note-taking: Ability to identify and record information that will later be used to support a thesis.

- Organization: Ability to plan, document, and track research to incorporate into a unified composition.

- Paraphrasing: Ability to restate an idea in your own words.

- Summarizing: Ability to restate in your own words the main ideas and key details of a text.

- Synthesis: Ability to combine information from different sources and make connections among them to form a new conclusion or deeper understanding of a topic.

- Technology: Ability to use computers, databases, and other forms of technology to conduct research.

- Time management: Ability to plan research tasks over several weeks or months.