5.8: Spotlight on . . . Profiling a Cultural Artifact

- Page ID

- 134896

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Read in the profile genre to understand how conventions are shaped by purpose, language, culture, and expectation.

- Read one of a diverse range of texts, attending to relationships among ideas, patterns of organization, and interplay between verbal and nonverbal elements.

- Analyze a composition in relation to a specific historical and cultural context.

If you would like to profile a subject other than a person, you may be unsure of how to make such a focus work. This section features a profile of a cultural artifact and discusses how the elements of profile writing work within the piece.

First, here is some background to help you better understand the blog post: On December 7, 1941, Japanese fighter planes attacked the United States military base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, damaging or destroying more than a dozen ships and hundreds of airplanes. In direct response to this bombing and to fears that Americans of Japanese descent might spy on U.S. military installations, all Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans living on America’s West Coast—about 120,000 men, women, and children in all—were detained in internment camps for the remainder of the war.

As you will read in the profile, people living in the camps created newspapers for fellow detainees; the subject of this profile is the newspapers themselves. Author Mark Hartsell published his profile of the newspapers, Journalism, behind Barbed Wire (https://openstax.org/r/barbedwire) , on the Library of Congress blog on May 5, 2017. Look at these notes to find out how profile genre elements can work when the writer focuses on a cultural artifact such as these newspapers.

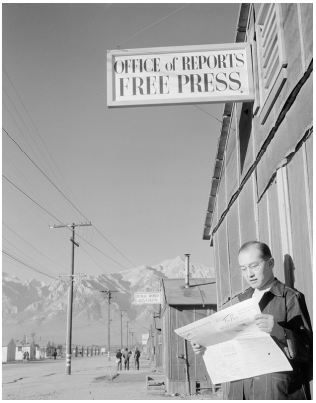

Figure \(5.8\) Roy Takeno, editor of the Manzanar Free Press, reads the newspaper at the internment camp in Manzanar, California, 1943. (credit: Ansel Adams/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

As you find when you click on the link above to visit the blog post, Hartsell uses images to show his subject to readers. Providing images can be a particularly strong choice for profiles of places or cultural artifacts.

For these journalists, the assignment was like no other: Create newspapers to tell the story of their own families being forced from their homes, to chronicle the hardships and heartaches of life behind barbed wire for Japanese-Americans held in World War II internment camps. “These are not normal times nor is this an ordinary community,” the editors of the Heart Mountain Sentinel wrote in their first issue. “There is confusion, doubt and fear mingled together with hope and courage as this community goes about the task of rebuilding many dear things that were crumbled as if by a giant hand.” Today, the Library of Congress places online a rare collection of newspapers that, like the Sentinel, were produced by Japanese-Americans interned at U.S. government camps during the war. The collection includes more than 4,600 English- and Japanese-language issues published in 13 camps and later microfilmed by the Library. “What we have the power to do is bring these more to the public,” said Malea Walker, a librarian in the Serial and Government Publications Division who contributed to the project. “I think that’s important, to bring it into the public eye to see, especially on the 75th anniversary.… Seeing the people in the Japanese internment camps as people is an important story.”

Although the blog places almost every sentence in its own “paragraph” for easier online readability, the first four sections function as a cohesive opening paragraph as presented here. Notice how the author supports his points with information synthesized from a variety of sources: quoted material from both the newspapers and one of the project’s curators, background, historical context, and other factual information.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order that allowed the forcible removal of nearly 120,000 U.S. citizens and residents of Japanese descent from their homes to government-run assembly and relocation camps across the West—desolate places such as Manzanar in the shadow of the Sierras, Poston in the Arizona desert, Granada on the eastern Colorado plains. There, housed in temporary barracks and surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers, the residents built wartime communities, organizing governing bodies, farms, schools, libraries. They founded newspapers, too—publications that relayed official announcements, editorialized about important issues, reported camp news, followed the exploits of Japanese-Americans in the U.S. military and recorded the daily activities of residents for whom, even in confinement, life still went on. In the camps, residents lived and died, worked and played, got married and had children. One couple got married at the Tanforan assembly center in California, then shipped out to the Topaz camp in Utah the next day. Their first home as a married couple, the Topaz Times noted, was a barracks behind barbed wire in the western Utah desert.

This section offers additional background information and information from secondary research, woven with specific details to help readers imagine the backdrop for the newspaper writing. Hartsell offers a brief overview of typical content found in these newspapers; this description indicates that he has reviewed primary documents. The section concludes with a brief anecdote to show the human face of the original camp newspaper audience.

The internees created their publications from scratch, right down to the names. The Tule Lake camp dubbed its paper the Tulean Dispatch—a compromise between The Tulean and The Dusty Dispatch, two entries in its name-the-newspaper contest. (The winners got a box of chocolates.) Most of the newspapers were simply mimeographed or sometimes handwritten, but a few were formatted and printed like big-city dailies. The Sentinel was printed by the town newspaper in nearby Cody, Wyoming, and eventually grew a circulation of 6,000.

After covering background and context, Hartsell turns to focus on his profile subject. He discusses specific details of naming and producing the newspapers; he also includes information about the writers and their decisions regarding newspaper content.

Many of the internees who edited and wrote for the camp newspapers had worked as journalists before the war. They knew this job wouldn’t be easy, requiring a delicate balance of covering news, keeping spirits up and getting along with the administration. The papers, though not explicitly censored, sometimes hesitated to cover controversial issues, such as strikes at Heart Mountain or Poston. Instead, many adopted editorial policies that would serve as “a strong constructive force in the community,” as a Poston Chronicle journalist later noted in an oral history. They mostly cooperated with the administration, stopped rumors and played up stories that would strengthen morale. Demonstrating loyalty to the U.S. was a frequent theme. The Sentinel mailed a copy of its first issue to Roosevelt in the hope, the editors wrote, that he would “find in its pages the loyalty and progress here at Heart Mountain.” A Topaz Times editorial objected to segregated Army units but nevertheless urged Japanese-American citizens to serve “to prove that the great majority of the group they represent are loyal.” “Our paper was always coming out with editorials supporting loyalty toward this country,” the Poston journalist said. “This rubbed some… the wrong way and every once in a while a delegation would come around to protest.”

People reading these newspapers in current times may be surprised that such newspapers often featured content with a focus on loyalty to the United States. While Hartsell does not dig deeply into alternative views held by internees, he does indicate that some disagreed with the emphasis on such content. Readers are often interested in learning surprising or counterintuitive information about a profile subject.

… (section removed)

As the war neared its end in 1945, the camps prepared for closure. Residents departed, populations shrank, schools shuttered, community organizations dissolved, and newspapers signed off with “–30–,” used by journalists to mark a story’s end. That Oct. 23, the Poston Chronicle published its final issue, reflecting on the history it had both recorded and made. “For many weeks, the story of Poston has unfolded in the pages of the Chronicle,” the editors wrote. “It is the story of people who have made the best of a tragic situation; the story of their frustrations, their anxieties, their heartaches—and their pleasures, for the story has its lighter moments. Now Poston is finished; the story is ended. And we should be glad that this is so, for the story has a happy ending. The time of anxiety and of waiting is over. Life begins again.”

Hartsell closes with a chronological structure, concluding his piece with the closing of the internment camps and their newspapers. He allows the voices of the editors to have the last word.

Publishing Your Profile

Because your individual profile is about someone or something related to campus, once you have developed your final draft, you may want to share your work with others at your school. Here are some suggestions:

Group Publication

One option for sharing your work is to create a class book that includes the profiles each student has written. As an alternative, each class member might contribute their own autobiographical profile in which they highlight a moment when they witnessed or enacted an admirable trait. When the individual pieces are complete, class members will work in teams to collect, compile, introduce, and produce the essay collection. The instructor or one of the class teams might compose an afterword to explain the project. The final project could be housed in the campus archives or linked on the campus website.

Campus Newspaper

Another option is to work either individually or in a small group to build on your profile about someone or something of interest to other students, faculty, or staff at your school. Check with the editor of your campus newspaper to learn whether they have suggestions for a revised angle, if needed, and whether they would be interested in publishing your completed profile.