5.5: Writing Process- Focusing on the Angle of Your Subject

- Page ID

- 134867

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Plan a research calendar.

- Conduct primary research, including field observations and interviews.

- Conduct secondary research, drawing on credible academic and popular sources.

- Compose an email that meets professional standards of the genre.

- Synthesize research findings using elements of the profile genre to create a written profile.

- Give and receive constructive feedback in peer review exercises.

- Revise a draft in response to feedback.

Now that you are familiar with the structure and content of profiles, you are ready to write one of your own. This section will show you how to apply the ideas and genre elements presented earlier in this chapter to develop your profile essay.

Summary of Assingment: A Profile in Courage or Other Admirable Trait

For this assignment, you will develop an essay that profiles the courage—or another admirable aspect—of someone or something associated with your college campus. You will create a profile of a person, group, place, or event that exemplifies the admirable aspect as you define it. For your profile, you will conduct the specific kinds of research done by profile writers: interviews, field research, and secondary research from credible sources.

Once you have compiled your research, you will decide on the focus and angle of your piece, then plan and develop your draft. You will also participate in peer review to receive guidance for any needed revisions. Throughout the process, you will focus on developing an essay that shows readers how your subject exemplifies the admirable trait you have chosen.

Another Lens. Another option for this assignment is a group writing project for your class or smaller groups within the class. Your instructor will decide whether the project will be completed by the whole class or smaller groups. With your peers, you will write a collaborative profile in courage of your class or group as a whole, showing how you all exemplify courage together. All students will contribute anecdotes about courage from their own lives in addition to conducting all other research on which profiles are based. The class or group will then work together to organize, draft, revise, edit, and proofread the collective composition.

Defining the Admirable Trait

Before beginning your profile, choose the admirable trait on which you will focus, and then create your own definition of it. This definition will help you select your subject and focus your research. Consider including the definition in your final product as well.

First, to decide on the trait, follow these steps:

- Set a timer for five minutes. During that time, write or record a comprehensive list of traits you admire in other people. Include a wide range of possibilities, such as “humor,” “generosity,” “patience,” and so on. To generate a robust list, think also of the people you admire, and then pinpoint the attributes you admire about them.

- Consider all of the traits you have listed, and select one to focus on for this project.

Next, use one or more of the following methods to begin defining the aspect of the subject that you admire:

- Think about the admirable trait you have chosen, and write down a few words or phrases that you associate with it. • Assemble a collage of images that make you think of the admirable trait.

- Write brief notes about moments when you have personally shown the trait you are focusing on—or about times you have seen others exhibit this trait.

Looking at all of these notes, write your personal definition of the admirable trait. Your draft definition will probably evolve as you develop your profile. If so, great! That means you have been thinking more about the idea. Here is a sample definition of an admirable trait: Kindness is grace in action; it shows itself when people are willing to truly listen to others and to understand the world from another vantage point. People embody kindness when they choose to respond gently rather than angrily or when they help others without complaining.

Choosing a Subject

Now that you have a working definition of the trait you are using to focus your profile, you can choose your subject. Members of the campus community are usually willing subjects: professors, librarians, resident assistants, alumni, staff, and coaches, to name a few. You might also consider buildings, public spaces, or public art on campus. In addition, the local community may contain potential subjects—for example, business owners, city administrators, and other local individuals, groups, or events peripherally associated with your school. Also consider discussing your project with an archivist if one is available on campus or in your community; these specialist librarians always have interesting subjects to recommend for research. Follow these steps to choose a subject:

- Jot down notes about intriguing buildings, public spaces, pieces of public art, people, events, and groups on or near campus.

- Do a quick online search—perhaps on the campus website—to see what information is available about several potential subjects that most intrigue you. Remember that this research is simply to narrow your options; you will conduct more careful and thorough research after making your final choice.

- Having gathered preliminary information, think about which potential subject best connects to the definition of the admirable trait you have developed. Also, think about which subject most interests you.

Now weigh the factors you have considered here, and choose the subject you would most like to pursue. If you are having trouble choosing between two subjects, discuss your options with your instructor or with someone in the campus writing center. Once you have chosen a subject, you can plan your research. You will need to schedule interviews, field observations, and time for secondary research before you begin organizing your findings and drafting your paper

Figure \(5.6\) Carmichael Library, University of Montevallo, April 19, 2007. Professor Art Scott Stephens speaks to research students at the Prints and Poems program. (credit: “Prints and Poems 2007” by carmichaellibrary/flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Preparing to Write: Conducting Research

Profile writers learn as much about their subjects as possible. Be sure to take advantage of all available sources of information, and follow up on new leads wherever you find them. After completing your research, you will be able to refine your angle and draft your piece. As you gather your research, keep your target audience in mind, and look for details about your subject that will interest them. For example, Carla D. Hayden included information about events in which John Lewis participated at the Library of Congress. These details would interest Library of Congress blog readers, the audience for this piece.

You will need to complete three kinds of research for your profile: interviews, field research and secondary research; see The Research Process: Where to Look for Existing Sources and The Research Process: How to Create Sources. These types of research are outlined in Table 5.1 for efficient planning and discussed in detail below

| Plan Your Research Calendar |

|

Interviews

|

|

Field Research

|

|

Secondary Research

|

Professional Email Standards

Before you begin to do research, you will need to contact people via email about setting up interviews or gathering other necessary information. To come across as a credible researcher, follow professional email protocol when contacting subjects for interviews or other information. Subjects will take you and your requests far more seriously when you follow the protocols in Table \(5.2\).

| Professional Email | |

| Take care to use professional email etiquette when contacting potential interview subjects. | |

|

|

Interviews

Talking with your subject—or a professional who knows a great deal about your subject—is often the best place to start your research. Interviews generally fall into the category of primary research, or research you collect directly for yourself. Try to interview your profile subject directly if the subject is a person. You also may find interviews with or about your subject that journalists have completed and published, though these would not be primary research. If you are unable to interview your subject directly, try to interview someone who has credible information about your subject; such interviews would be primary research as well. People who know, live, and work with your subject can provide additional, helpful background information. Try to set up a few short interviews with these people to deepen your insights.

The easiest way to conduct an interview is to schedule a brief, informal conversation in a comfortable setting. For a successful interview, have questions prepared and be ready to take notes as you talk. Following in Table \(5.3\) are sample questions you might ask. To add to this list, think about your preliminary research as well as the definition of the admirable trait you are using for your profile.

Note that you will need to cite any interviews you conduct, both within the text and in the Works Cited list. The Works Cited entry for an interview will read as follows:

[Last name of interviewee], [First name of interviewee]. Personal interview. Day Month (abbreviated) Year.

| Interview Planning Worksheet | |

|

If you are interviewing your subject:

|

If you are interviewing someone about your subject:

|

Thick Description

Another form of primary research is field observation. If at all possible, observe your subject in their element—watch them (with permission!) during their workday, spend an extended period of time in a related space, or watch available videos of your subject. In all cases, take thorough and detailed notes to create a thick description, or a careful record of every sensory detail you can capture—smells, sounds, sights, textures, physical sensations, and perhaps tastes. This thick description can provide meaningful details to illuminate the points in your piece. Meticulously record all sensory information about your subject and their setting, writing in-depth notes about what you see, smell, hear, feel, and taste. Remember to use words that express size, shape, color, texture, and sound. If you are taking notes on a person, describe their clothing, gestures, and physical characteristics. At the same time, take note of the interview setting. If the interview takes place in a neutral space, the setting can provide a backdrop for the profile. If the interview setting is a person’s room or apartment, record the details that tell the most about your subject’s special interests. If you are not used to taking these kinds of notes, practice doing so by following the steps in Table \(5.4\).

| Practice Field Notes and Thick Description |

|

Practice creating field notes with a peer. Take about 10 minutes to record as much sensory information as possible.

When the 10 minutes are up, discuss the experience with your peer. Use these techniques to enliven the points you make in your profile. |

You will also need to cite your field notes, both within the text and in the Works Cited list. The Works Cited entry for the field notes should be arranged according to this model:

[Your last name], [Your first name]. Field notes. [Name of the department you are affiliated with], [Name of your university], Day Month (abbreviated) Year. Raw data.

Secondary Research and Other Written and Published Information

Profile writers supplement their primary research findings through secondary research, or research that others have completed and published. Ensure that any supplemental information you use comes from credible sources; these include peer-reviewed journals for academic sources and well-established, highly regarded organizations for public, nonacademic ones. Keep careful records of this research so that you can cite each source appropriately. Use the tools available from the Modern Language Association (https://openstax.org/r/modernlanguage) and in Research Process: Accessing and Recording Information and Annotated Bibliography: Gathering, Evaluating, and Documenting Sources for guidance in researching and managing source material. For more details on citing sources, see MLA Documentation and Format and APA Documentation and Format.

Additionally, ask your subject for their résumé and any writing samples they may have developed. While this type of research may not be available about your subject, as many ordinary people have not published anything, find and read any existing publications by or about your subject. Additionally, you can focus your secondary research on information related to your subject rather than about your subject specifically. For example, Carla D. Hayden, in writing the profile of John Lewis, could have researched Bloody Sunday more generally, or she could have found secondary research about the AIDS quilt to which she refers. To see how authors can use such secondary research, read the sample of student work later in this section as well as the blog post in Spotlight on . . . Profiling a Cultural Artifact.

Synthesizing Research

After you have completed your research, the next step is to synthesize it, or put it all together. You can simplify this task by filling in a graphic organizer such as Table \(5.5\) with your findings and potential angles you might take in your profile.

| Synthesizing: Putting Your Research Together | ||

| Source | Element | Potential Angle |

| List your sources by type: | List the elements you can draw from the sources—quotations, anecdotes, facts, background information, contextual information: | List potential angles you could take relating to the information in the other columns: |

| Interview(s) | ||

| Field observation location and date | ||

| Sources from secondary research | ||

Quick Launch: Consider the Angle

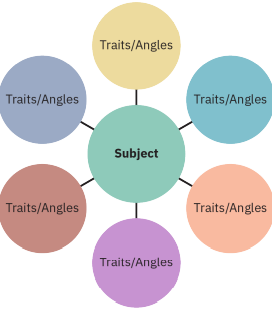

After completing and synthesizing your research, consider your information carefully to decide on the most compelling angle and supporting information for your audience. While your general angle is the idea of the admirable trait in relation to your subject, aim to develop a personal insight within that focus. Brainstorm different points you can make about the trait that may surprise and engage your audience. Review the table you completed for synthesizing information, and then complete a web diagram such as Figure \(5.7\) with possible ideas.

Figure \(5.7\) Planning web (CC BY 4.0; Rice University & OpenStax)

After considering your notes and the completed web, decide which angle will work best. To help you make that decision, think about the information you have gathered so far as well as potential audience appeal. Review the model texts in this chapter to determine how each presents a unique angle on its subject.

Drafting: Finalizing and Supporting Your Angle

Remember that the writing process is recursive, meaning you will move back and forth among the steps in the process multiple times rather than progress through each step only once. For example, you may decide to conduct a bit more research while you are drafting or after you have received feedback from peer review. To include this new research, you may need to rearrange the structure of your draft. As you draft, keep focused on your angle at all times. Losing focus and including irrelevant material may weaken your profile and cause readers to lose interest in the subject.

Organization

As discussed in Glance at Genre: Subject, Angle, Background, and Description, profiles can be organized in several ways: chronologically, spatially, or topically. Review the information you inserted in response to Table \(5.1\), along with your admirable trait definition, to decide which organizational strategy would work best for your piece. Then use the following sections to organize the introduction, body, and conclusion of your work. When organizing your draft, think about where to place each piece of information to convey your points most effectively. Rather than using a strict chronological structure throughout your draft, you may find your piece is more effective if you begin with a topical structure and then provide some information chronologically.

Introduction and Thesis

Like introductions in most of the writing you do, the profile introduction establishes some background and context for readers to understand your main point. Think about what readers need to know in order to appreciate your angle, and include that information in the introduction. Some writers prefer to compose their introductions first, whereas others wait until after they have developed a draft of the body. Whichever strategy you use, be sure that the introduction engages readers so that they want to continue reading. Refer to the sample texts in this chapter for models of introductory texts.

Remember, too, that your thesis should appear as the last sentence, or close to the end, of the introduction. For the profile, your thesis would be a sentence or two explaining your angle. For example:

- [Name of subject] showed [the admirable trait] not only in [doing something that shows the trait] but even more so by refusing to [accept or participate in something].

- [Name of subject] plays a unique part in the [history, life, culture] of [place, group] because [reason for angle].

Try one of these models, or a variation of it, as the first draft of your thesis.

Body Paragraphs

Each body paragraph should support the angle you have taken, advancing your thesis, or main point. For suggestions on developing body paragraphs in narrative writing, see Literacy Narrative: Building Bridges, Bridging Gaps and Memoir or Personal Narrative: Learning Lessons from the Personal. For each paragraph, synthesize details—examples, anecdotes, quotations, location, background information, or descriptions of events—from more than one source to support your angle. By including all of these elements, necessary explanations, and a combination of narrative and reporting, you will create the strongest possible profile piece. See the section See the section Spotlight on . . . Profiling a Cultural Artifact to explore examples of how these elements can work in the paragraphs of a blog post profiling a cultural artifact. In each paragraph, consider drawing on the following:

- Show and Tell. In balancing between interviews and biographies, profile writers use both narrative and reporting techniques—that is, they both show and tell readers information about the subject. As you read your notes, decide which elements you will use to show readers something about your subject and which elements you will simply report.

- Quoted Material. If your subject has said something in a memorable way, present their words directly to readers. Doing so increases your readers’ sense of the subject’s voice.

- Anecdotes. Very brief scenarios or stories about something your subject has done, or about the subject itself, contribute to readers’ understanding. Often, anecdotes reflect field research, showing the subject “in action” or reflecting what others think about the subject. For example, Carla D. Hayden relates anecdotes about John Lewis’s actions leading 600 protesters in Selma, Alabama.

- Background Information. You may have one or more paragraphs in which you present background information—but only information that is relevant to the profile. If you highlight an individual’s success or their contributions to society or a cause, then that person’s humble beginnings may be relevant as a contrast. Hayden mentions Lewis’s impoverished youth for this reason. Including background information helps readers place the subject in time and within their culture.

- Location. Placing your subject in a setting, in either the past or the present, helps readers understand and visualize the subject in a particular context. Be sure to include location in at least one body paragraph.

The sample texts in this chapter provide models for you to use when developing your draft. Use a graphic organizer like Table \(5.6\) to identify the following profile genre elements in one or more of the model texts featured in this chapter: Annotated Sample Reading, the student sample in this section, or Spotlight on … Profiling a Cultural Artifact. Remember that single paragraphs often synthesize more than one type of information and use more than one strategy.

| Strategies Used in This Chapter's Sample Texts | Example of the Strategy That You Found in One or More Sample Texts |

| Draw the reader in with a brief, compelling description of the subject. | |

| Offer quoted material. | |

| Connect to both current and historical contexts. | |

| Offer background information. | |

| Use narrative, or storytelling, techniques. | |

| Use reporting techniques, providing supporting facts and answering questions of who, what, when, where, why, and how. | |

| Provide a brief anecdote. | |

| Offer “thick description” from field notes. | |

| Synthesize information from multiple sources within a paragraph. |

Additionally, tone, a writer’s attitude toward their subject, is particularly important in profiles because it conveys authenticity to readers. If you praise a subject but your tone or attitude reflects detachment or lack of interest, readers will notice the discrepancy. Hayden’s attitude toward her subject, John Lewis, is one of respect and admiration. If you are writing about someone courageous, then your tone will probably be similar to hers. Remember, though, that you are the narrator, and thus you set the tone. If you insert quotations by people who don’t think as you do, make sure that doing so suits your purpose. By including information in the areas covered above and maintaining a consistent and appropriate tone, you will have the basis of a strong and engaging profile.

Conclusion

The conclusion is your opportunity to pull all the points of the essay together. Many writers like to restate the main point they have sustained throughout the essay in the conclusion. Another strong move for the conclusion is to tell readers the exigency of the piece—in other words, why the information is important and why they should care about it. After your introduction and body are complete, read through your draft; this process will often give you a sense of what still needs to be said in the conclusion. Refer to the sample texts in this chapter for models of conclusion paragraphs.

Review Your Draft

After you have written a rough first draft, including the introduction and conclusion, read the entire piece three times:

- Revise. Read once for the big picture to judge whether you have enough content and whether the content is arranged in a way that makes sense. Revise your work as needed.

- Edit. Read a second time for mid-level concerns such as sentence variety, word choice, and consistent use of tenses: Editing Focus: Verb Tense Consistency. Think about whether you need to break some sentences apart or combine some sentences for smoother flow. Follow the chronology of your profile to ensure that the narration stays in the present or past tense and that events are clearly set in time. Read your composition aloud to see whether you overuse some words. Edit your work as needed.

- Proofread. After editing, read through a third time with an eye on small details to proofread your work. Change spelling or punctuation as needed to meet the expectations of the rhetorical situation. Check that you have formatted according to the required style guide, or standards of writing, such as Modern Language Association (MLA) or American Psychological Association (APA) style.

Revisit these three steps after you have received feedback from the peer review exercise that follows. If you have access to a campus writing center, you may consult with tutors there for support at any stage of your writing process.

Peer Review: Written Responses

After you have developed a solid draft, you are ready to receive feedback from your peers. To prepare for peer review, reread the assignment prompt in Writing Process: Focusing on the Angle of Your Subject and the assessment rubric in Evaluation: Text as Personal Introduction. Then, read your peer’s entire profile before giving feedback. In your feedback, strive to be both clear and kind—clearly state the strengths and weaknesses of the text in the most supportive way possible. If you need guidance, use the model sentences in Table \(5.7\) to structure your feedback.

| Peer Review Feedback Model Sentences |

|

After reading your peer’s profile all the way through, use Table \(5.8\) to provide thoughtful and detailed feedback.

| Date |

Review of [peer] by [insert your name] |

| Profile Genre Element | Feedback for Your Peer |

| Subject | What interests you about your peer’s subject? What information could your peer provide to deepen that interest? |

| Angle | What angle has your peer taken in this draft? What suggestions do you have for refining the angle? |

| Structure | How has your peer organized the profile? If you would recommend a different structure, what would you recommend, and why? |

| Paragraph Focus (anecdote, quotes, facts, background, and context) | Has your peer included an array of genre elements in the paragraphs? How could your peer strengthen this aspect of the work? |

| Tone, Tense, and Description |

Is your peer’s tone, or written attitude, appropriate for the profile? Why or why not? What suggestions do you have for strengthening or changing the tone? Are verb tenses consistent? If not, how might your peer adjust them? How might your peer show readers aspects of the subject as well as tell about them? |

| Research |

How does your peer’s draft show evidence of

|

| Audience | What suggestions do you have for your peer to connect better with the intended audience? |

| Additional Comments | In what other ways might your peer strengthen the draft? |

Revising: Incorporating Written Responses

After you have received feedback from your peer(s), read it carefully. If you have received feedback from more than one peer, strongly consider addressing comments on which they agree. If you have received comments encouraging you to make revision, editing, and proofreading changes, prioritize revision—making major changes in content, structure, and organization. You may need to add, delete, or rearrange information or the way in which you present the material. You may rearrange information within paragraphs or add topic sentences if needed. Much of the feedback your peers give you based on the form above will probably fit into the category of revision.

Evaluate Yourself

Another way to approach revision is to compare and contrast your work against the rubric for the assignment in Evaluation: Text as Personal Introduction, which guides you through the process of evaluating your work using the standards given in the assignment rubric.

| Use the Rubric to Improve Your Draft |

|

|

|

| Use your notes from this worksheet to revise, edit, and proofread your work. |

Revised Draft Profile Sample

This section provides one example of a revised profile draft written by a first-year college student. As you will read, the admirable quality that Houston Byrd focuses on in this essay is that his subject, a bricks-and-mortar video store, offers “a crucial and important service to its community.” You will also see the ways in which Byrd both “shows and tells” readers about his subject, offering information drawn from each type of required research: interview, field observation, and secondary sources. Byrd has chosen to insert himself and his experiences of his subject fully into this profile. Review Glance at Genre: Subject, Angle, Background, and Description, and then read Byrd’s essay to see how well he incorporates the narrative and reporting profile genre elements in his draft.

After Byrd received peer feedback, he decided that his previous draft did not need much revision; he was happy with his structure, and the organization made sense to his readers. One peer suggested that Byrd insert topic sentences in each paragraph, but he ultimately decided not to do so because he thought his paragraphs held together well as written. As you revise your work in response to peer feedback, you may also choose to accept some suggestions while rejecting others.

Byrd paid close attention to peer feedback indicating that his draft had many long, complicated sentences; in the draft below, the originals are noted after the edited sentences. He also acted on feedback about verb tense consistency. Furthermore, Byrd made proofreading changes, such as adding the MLA-required right header and changing the placement of some punctuation marks. As with all writing, this draft could be improved even more with further revision. After reading the essay, discuss with a peer the revision, editing, and proofreading changes you would recommend if you were reading this draft for peer review.

Heaven Is in Toad Frog Alley

The realm of physical film, if not already dead, is dying. More so than decaying cellulose, the entire medium as an art form is declining. According to The Guardian, DVD and Blu-Ray sales were down this past holiday over 30% each (Sweney). Some say that streaming services and on-demand viewing are the culprits. Whatever the case, the answer is not so simple, and the notion is very alarming. The decrease in relevance of physical media is no secret. Mass closures of video rental powerhouses such as Blockbuster Video and Movie Gallery began at the turn of the decade.

The original sentence read: It is no secret that physical media has been on the decline, especially with the mass closures of video rental powerhouses such as Blockbuster Video and Movie Gallery near the beginning of the decade. This example demonstrates a pattern throughout the revised draft in which Byrd broke apart some of his longer sentences and improved their wording. Notice that he changes tense in the last sentence for a reason: the trend is happening now, but video rental stores began closing in the past.

Though the memory lives on in millennial nostalgia, the world of physical movie sales is not completely irrelevant. Many of the large rental chains have since closed down, but beyond the major highways is an all-butforgotten world of local video stores. In my home state, one store in particular, called Toad Frog Alley Videos, lives in that world, located in the small town of Cleveland, Alabama. I had the privilege of visiting the store and speaking with its owner, Kandy Little, about her experiences operating in a time when physical media is scarce. Through my visit and conversation, I have come to appreciate the importance of Toad Frog Alley Videos. I truly believe that the store provides a crucial and important service to its community, as well as highlights the nature of physical film and the need for preservation.

In this introductory paragraph, Byrd establishes the stakes for his profile subject, offering both background and context for understanding the video store’s importance to its community. He also makes some editing and proofreading changes to strengthen the draft and presents his main point, or thesis, here at the end of the introduction.

Miles off of I-65, a major Alabama interstate, Toad Frog Alley stands, an almost well-kept secret. The idea of such a welcoming business being hidden saddened me—and still does—but in turn gave the illusion of adventure. Driving through winding county roads to get there, I could feel the world almost disappearing into unexplored territory.

Original: There is a moment, winding through country roads, where the world seems to disappear into unexplored territory. Byrd corrected the sentence to get rid of a “there is” construction, a dangling modifier, and inconsistent verb tenses.

Suddenly, there were no street names, no lines on the pavement, and sometimes no pavement at all. At the end of one of these “not much of a road” roads stood Toad Frog Alley Videos.

Byrd changed the underlined verb from is to stands for a more vivid verb. He then changed it to the past tense to maintain consistency with the verbs he uses in relating his visit to the store.

My first impression stepping inside was awe. Shelves lining the walls reached from floor to ceiling, each packed full of titles, perfectly alphabetized and separated by genre.

Original: Lining the walls were shelves that reached from floor to ceiling. Each shelf was completely full of titles, which were perfectly alphabetized and separated by genre. In this case, Byrd combined, rather than separated, sentences to avoid repetition, substitute more active verbs, and vary sentence structure.

Between the walls were standalone shelves, organized in the same fashion. I expected a kind of personal collection, but I felt as if I had actually traveled back in time to the major rental stores of old (or rather of ten years ago). To community members, the setup meant another option for Saturday night, but for a film lover like me,

Original: for me, a film lover,

this place was heaven.

In the body of his draft, Byrd advances his thesis, drawing on information from each of the required types of sources.

After my initial feelings, I was hit with a second wave, one that can only be described as abysmal. At the front of the store was a counter, being worked by one employee. The register was clunky and archaic, which made

Original: something that makes

a public library look like the headquarters of Google. In the center of the store was a foldable table that read “FOR SALE.” On the table lay DVDs, either damaged or unwanted, strewn about with no rhyme or reason.

Original: The table was filled with DVDs, some damaged and some unwanted, strewn about with no rhyme or reason like the rest of the store.

Aside from me, there was only one patron, a middle-aged woman, shopping as if she had been there before but did not know what she wanted. I started to become depressed. I was not sure exactly what I had imagined, but I knew this place was nowhere close. I had convinced myself I was on a journey to find the “last great video store,” an oasis of film, flowing with patrons renting Milk and American Honey.

Original: I did not know what exactly I had imagined, but with my passion for physical film and rental stores alike, I had convinced myself I was on a journey to find the “last great video store,” an oasis of film, flowing with patrons renting Milk and American Honey. This sentence is another example in which Byrd broke a longer sentence apart and polished the wording.

Only when

Original: It was not until

I took a breath and began looking around was I able to see Toad Frog Valley for what the store

Original: it

was. Every blank wall space featured posters, equally sporting Oscar winners and underground art-house films.

This sentence provides a solid example of revising a “there were” or “there are” sentence construction; the original read: There were posters on every blank wall space, not just of each year’s Oscar winner, but underground art-house films as well.

The endcaps of each standalone shelf were filled with top picks, recent releases, or staff choices.

Here, Byrd revises for varied word choice; the original read: top picks, recent releases, or staff picks.

A television in the corner softly played a film of the employee’s choice. Toad Frog Alley

Original: This

may not have been the perfect haven for cinephiles and collectors that I had hoped, but it showed an undeniable element of care. The store was something of a museum, one that lets people borrow the items they love. I left with a smile on my face and a movie in my hand.

I want to believe that everyone has experienced a similar video store moment. If that were true, though, why did so many close in the first place?

Original: I want to believe that if everyone could experience a moment of awe in a video store, then the demand would resurface, but if that were true, why did so many close in the first place?

Why also are stores like Toad Frog Alley still operating? Back in 2010, when rental chains were beginning to close doors indefinitely, many entertainment news sites noticed a trend. Among them was The Hollywood Reporter, which noted that over 35% of independent video stores had tanning beds. They reported the trend, saying, “[Independents] use every niche they can think of to survive and be respected in their communities” (Bond). While tanning beds may look like the supplemental savior for many locally owned stores, this notion

Here, Byrd defines the word this by inserting the word notion.

is not necessarily the case, says Kandy Little. Kandy is the owner of Toad Frog Valley Video Store and has been since 1995.

The tense shifts to present when Kandy Little is discussed but returns to the past when Byrd relates her background.

Ironically, Kandy bought a tanning salon in hopes of opening a video store. At the time, there was a much higher demand for rentals in almost every community, and Toad Frog Alley was no exception. Though she admits tanning has increased over the years (with rentals, of course, declining), to Kandy, tanning was not the savior. “[Toad Frog Alley Videos] is still open because I work it myself most of the time,” she says. “No one else will take care of your business as well as you do.” With an inventory of over 5,000 films, Kandy believes that physical media is important for her community. Local business is important for creating jobs and city revenue, and Kandy provides both through her love of movies.

Even though Toad Frog Alley is doing well, the scarcity of rental stores is something to consider. In the digital age, media is accessible to practically everyone. Streaming services such as Netflix and Hulu have made media available for viewers without requiring them to leave their homes. For physical rentals

Original: As far as physical rentals go.

nationwide kiosks called Redbox are set up in major grocery stores and pharmacies. In largely populated areas, these services have contributed to the downfall of video stores. In small towns across the country, however, many stores like Toad Frog Alley are still alive.

Original: In largely populated areas, these services have contributed to the downfall of video stores, but in rural America, many stores like Toad Frog Alley are still alive. This revision heightens the contrast between populated areas and small towns.

In 2018, the Harvard Political Review looked into why rural areas are struggling socioeconomically. The research concluded that the problem comes from the inability to keep the attention of a younger generation. The idea of the “American Dream” is largely accompanied by main streets, small towns, and mom-and-pop shops. Unfortunately, countryside communities are suffering, despite featuring many of these elements.

Original: Though the idea of the “American Dream” is largely accompanied by main streets, small towns, and mom-and-pop shops, rural communities have seen drastic population decreases even while holding many of these. The revision breaks the original sentence apart and makes stronger, clearer word choices.

Farming, a large majority of pastoral industry, has become increasingly mechanized with technological advancement. On top of that, failing education and inadequate healthcare in underfunded areas have contributed to population loss as well. Many young people are unwilling to live in rural America,

Original: in these rural areas,

and thus jobs

Deleted: , one of the largest incentives in most communities,

have become scarce. The Review states that “ultimately, the only way citizens will be attracted to small towns is if the quality of life is attractive and sustainable… [but] the growing demand of the U.S. economy will continue drawing people toward… [a] quality of life often deemed synonymous with urban living” (Elkadi). This cycle leaves many rural settings unappealing, not only to residents but also to businesses like Internet providers. In many cases, rural areas are deemed unprofitable for modern services. Descriptions so negative contribute to the lack of digital services available to communities. Businesses

Original: Stores

such as Toad Frog Alley thus provide a necessary service for a town that may have little access to digital content.

All of these factors raise

Original: This raises

a question: Is physical media doomed to a state of limbo in rural communities? Some believe film was meant to die, and should. Following the controversial shutdown of the “classic films” streaming service FilmStruck, Professor Katherine Groo shared a perspective in The Washington Post: “The collapse of FilmStruck might go some way toward reminding us of the fundamental virtuality [sic] of film and film spectatorship” (Groo). Groo goes so far as to ask “whether [FilmStruck’s catalog listings] are the works we need to rescreen or urge others to discover.” Groo does not lament the death of FilmStruck as film “erosion” or “erasure.”

In the original, the previous sentence occurred later in the paragraph; Byrd moved it here in the revision to present the information in a way that made more sense for readers.

She mentions different film archives, like the Library of Congress and Kanopy, doing open-access experimentation, but overlooks an important factor. Groo asserts that only the privileged are able to access a paid service, but she neglects rural areas and others that cannot access archives, paid or free.

Deleted: For people like Kandy Little,

Toad Frog Alley remains important for the enjoyment and education of people in the town that film provides. As technology keeps progressing, archaic forms of media consumption are necessary for areas that do not yet have access to the new technologies. Kandy predicts this, and more, when asked about the digital age and the coexistence of physical and online media:

Original: Kandy predicts this, and more, when I asked her how she felt about the digital age, and the coexistence of physical and online media:

“Studios are already giving exclusive rights to different cable companies. Once the avenues are spread out, customers will have to pay more for accessing media. The video store is here offering better prices and more media in one place.” To her, the transition back into physical media is only a matter of time.

As a proponent of physical media, I am thankful that Kandy and Toad Frog Alley exist. Though nothing is wrong with enjoying the luxuries of streaming, and digital film preservation is admirable, the market is becoming saturated. Saturated markets lead to higher prices and necessitate multiple subscriptions just to access desired films.

Original: Though it is not wrong to enjoy the luxuries of streaming, and digital film preservation is admirable, the market is becoming saturated, which leads to higher prices and necessitates multiple subscriptions just to access desired films.

Though people in rural communities are still able to rent videos, they would be left behind in the case of film becoming solely digital. Video stores provide important business and atmosphere to communities. Even though digitizing film is more affordable and accessible to many people, it may not be what is best for both films and consumers.

In the original, these sentences were combined with , and.

For those like me, with a passion for film, the only reciprocity for the love that video stores instill is to show love in the form of support. As Kandy eloquently said at the end of our interview, “I really don’t have a favorite film. I just love films.”

In referring a past event while he narrates in the present tense, Byrd uses the past tense.

Works Cited

Bond, Paul. “Video Rental Stores’ Bizarre Survival Strategy.” The Hollywood Reporter, 14 Sept. 2010, www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/video-rental-stores-bizarre-survival-27851.

Elkadi, Nina. “Keeping Rural America Alive.” Harvard Political Review, 13 October 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20181013...america-alive/.

Groo, Katherine. “FilmStruck Wasn’t That Good for Movies. Don’t Mourn Its Demise.” The Washington Post, 3 Dec. 2018, www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2018/12/03/filmstrucks-demise-could-be-good-movies/.

Little, Kandy. Personal interview. 25 June 2019.

Sweney, Mark. “‘Christmas from Hell’ Caps Bad Year for High Street DVD Sellers.” The Guardian, 3 Jan. 2019, www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jan/03/christmas-from-hell-caps-bad-year-for-high-street-dvd-sellers.