4.4: Annotated Sample Reading- from Life on the Mississippi by Mark Twain

- Page ID

- 134150

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Read for understanding, showing that genre conventions are shaped by purpose, culture, and expectation.

- Analyze relationships between ideas and patterns of organization in a nonfiction text

Introduction

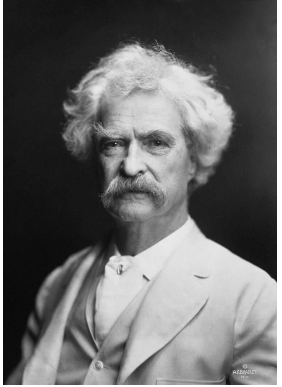

Figure \(4.5\) Mark Twain, 1907 (credit: “Mark Twain” by A.F. Bradley/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

An image in literature is a description that engages one of the five senses. Details rich in imagery appeal to readers’ emotions, create new meaning, and draw an audience into the story. Sensory images—what the narrator sees, hears, tastes, feels, and smells—should be specific and contain emotional content that enhances your writing. When you write your personal narrative, you will use imagery to engage readers, convey meaning, and bring your story to life.

In the text excerpt you are about to read, Mark Twain (1835–1910) uses imagery to place readers with him aboard a steamboat on the Mississippi River as Mr. Bixby trains him to pilot it. As you read, put yourself in the shoes of the narrator—Mark Twain. Notice how vividly he describes sensory experiences and how they enhance your understanding of his purpose.

Twain lived in a pre–Civil War America in which slavery was accepted and prevalent. He used his literature to criticize slavery and hierarchical social codes of the American South, though he wasn’t necessarily an outspoken opponent in his public life. Twain provides an example of the ways in which literature can subtly influence the beliefs and identities of generations of readers. Visit Project Gutenberg (https://openstax.org/r/ projectgutenberg) for the full text of Life on the Mississippi.

Living By Their Own Words

The Storyteller's World: Entering through Imagery

Figure \(4.6\) In this illustration, appearing in Life on the Mississippi, the steamboat is an older vessel but is similar to the one in Twain’s memoir. (credit: “MISSISSIPPI STEAMBOAT - FIFTY YEARS AGO” by Samuel Langhorne Clemens/ Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Mr. Bixby served me in this fashion once, and for years afterward I used to blush even in my sleep when I thought of it. I had become a good steersman [a person steering a boat or ship]; so good, indeed, that I had all the work to do on our watch, night and day; Mr. Bixby seldom made a suggestion to me; all he ever did was to take the wheel on particularly bad nights or in particularly bad crossings, land the boat when she needed to be landed, play gentleman of leisure nine-tenths of the watch, and collect the wages. The lower river was about bank-full, and if anybody had questioned my ability to run any crossing between Cairo and New Orleans without help or instruction, I should have felt irreparably hurt. The idea of being afraid of any crossing in the lot, in the day-time, was a thing too preposterous for contemplation. Well, one matchless summer’s day I was bowling down the bend above island 66, brimful of self-conceit and carrying my nose as high as a giraffe’s, when Mr. Bixby said,—

Point of view. Twain writes in first person, using the pronouns I and me.

Exposition. Though the excerpt starts in the middle of a chapter of a larger work, this paragraph begins an anecdote that Twain relates about a specific incident in his time in training. The paragraph acts as the exposition, establishing the setting, characters, and lead-in to the conflict related in the anecdote.

Reflection. Twain’s reflection of the memory, saying he would “blush even in my sleep,” reveals his embarrassment in a way that readers can relate to.

“I am going below a while. I suppose you know the next crossing?”

This was almost an affront. It was about the plainest and simplest crossing in the whole river. One couldn’t come to any harm, whether he ran it right or not; and as for depth, there never had been any bottom there. I knew all this, perfectly well.

“Know how to run it? Why, I can run it with my eyes shut.”

Tone. In this dialogue, the narrator takes on a tone of confidence, which helps develop his own voice and character.

Dialogue. Twain uses dialogue to recreate the scene and reveal characters.

“How much water is there in it?”

“Well, that is an odd question. I couldn’t get bottom there with a church steeple.”

“You think so, do you?”

The very tone of the question shook my confidence. That was what Mr. Bixby was expecting. He left, without saying anything more. I began to imagine all sorts of things. Mr. Bixby, unknown to me, of course, sent somebody down to the forecastle [forward part of the ship, below the deck] with some mysterious instructions to the leadsmen, another messenger was sent to whisper among the officers, and then Mr. Bixby went into hiding behind a smoke-stack where he could observe results. Presently the captain stepped out on the hurricane deck [an upper deck on a ship]; next the chief mate appeared; then a clerk. Every moment or two a straggler was added to my audience; and before I got to the head of the island I had fifteen or twenty people assembled down there under my nose. I began to wonder what the trouble was. As I started across, the captain glanced aloft at me and said, with a sham uneasiness in his voice,—

Vivid Details and Imagery. Twain builds tension through vivid detail and imagery that recreates the sounds and paints a picture of his experience. From the whispers of the messengers to the sight of more and more people appearing on the deck to observe the narrator, readers can almost feel the narrator becoming more nervous.

Rising Action. The reader begins to understand the conflict through the sequence of events. This rising action builds tension by contrasting Twain’s earlier stated confidence with his increasing anxiety.

“Where is Mr. Bixby?”

“Gone below, sir.”

Dialogue. Twain employs dialogue to advance the plot and simultaneously increase tension, thus defining the conflict. The dialogue here signals the narrator’s move from confidence to anxiety, the next line indicating that the captain’s questioning “did the business” for him. Dialogue also helps establish authenticity and recreate “reality” for readers, allowing them an opportunity to “witness” the scene and the characters directly.

But that did the business for me. My imagination began to construct dangers out of nothing, and they multiplied faster than I could keep the run of them. All at once I imagined I saw shoal [shallow] water ahead! The wave of coward agony that surged through me then came near dislocating every joint in me. All my confidence in that crossing vanished. I seized the bell-rope; dropped it, ashamed; seized it again; dropped it once more; clutched it tremblingly once again, and pulled it so feebly that I could hardly hear the stroke myself. Captain and mate sang out instantly, and both together,—

Vivid Description. Twain moves the plot toward the climax in this paragraph, particularly with his description of the dangers multiplying and the peril he imagines.

Mood. In this section, Twain creates a frazzled and frantic mood through not only the details and description but also the sentence structure. Particularly in the sentence “I seized the bell-rope; dropped it, ashamed; seized it again; dropped it once more . . . ,” the short, connected clauses and phrases and the repetition of the words dropped and seized all add to the sense of panic.

“Starboard lead there! and quick about it!”

This was another shock. I began to climb the wheel like a squirrel; but I would hardly get the boat started to port [the left side of the ship when a person on board is facing forward] before I would see new dangers on that side, and away I would spin to the other; only to find perils accumulating to starboard [the right side of the ship when a person on board is facing forward], and be crazy to get to port again. Then came the leadsman’s sepulchral [bleak, morbid] cry:—

Organization. After the introduction in which Twain writes in the present tense to indicate he will tell an embarrassing story from the past, the rest of the passage follows a chronological organization, recounting the event from beginning to end.

D-e-e-p four!”

Deep four in a bottomless crossing! The terror of it took my breath away.

“M-a-r-k three! . . . M-a-r-k three . . . Quarter less three! . . . Half twain!”

This was frightful! I seized the bell-ropes and stopped the engines.

“Quarter twain! Quarter twain! Mark twain!”

Dialogue. Here, the dialogue emphasizes the narrator’s terror and leads to the climax.

I was helpless. I did not know what in the world to do. I was quaking from head to foot, and I could have hung my hat on my eyes, they stuck out so far.

Hyperbole. Twain uses a combination of sensory detail and hyperbole, or exaggeration, to emphasize how panicked he feels in the moment.

“Quarter less twain! Nine and a half!”

We were drawing nine! My hands were in a nerveless flutter. I could not ring a bell intelligibly with them. I flew to the speaking-tube and shouted to the engineer,—

“Oh, Ben, if you love me, back her! Quick, Ben! Oh, back the immortal soul out of her!”

Climax. In this part of the story the narrator calls out for help as the tension reaches its peak.

I heard the door close gently. I looked around, and there stood Mr. Bixby, smiling a bland, sweet smile. Then the audience on the hurricane deck sent up a thundergust [roar] of humiliating laughter. I saw it all, now, and I felt meaner than the meanest man in human history. I laid in the lead, set the boat in her marks, came ahead on the engines, and said:—

Vivid Details. The narrator describes Mr. Bixby’s “bland” smile, contrasted with the uproarious laughter of the rest of the group. He also uses vivid details to describe his own reaction: he “felt meaner than the meanest man in human history.”

Falling Action. After it is revealed that the group was tricking Twain, the tension begins to dissipate.

“It was a fine trick to play on an orphan, wasn’t it? I suppose I’ll never hear the last of how I was ass enough to heave the lead at the head of 66.”

“Well, no, you won’t, maybe. In fact I hope you won’t; for I want you to learn something by that experience. Didn’t you know there was no bottom in that crossing?”

“Yes, sir, I did.”

“Very well, then. You shouldn’t have allowed me or anybody else to shake your confidence in that knowledge. Try to remember that. And another thing: when you get into a dangerous place, don’t turn coward. That isn’t going to help matters any.”

Theme. Through this dialogue, Twain introduces the message of the story. More than providing an amusing recollection about a time he was embarrassed, his purpose is to convey the message that it is important to rely on your knowledge and training rather than allow fear to rule.

It was a good enough lesson, but pretty hardly learned. Yet about the hardest part of it was that for months I so often had to hear a phrase which I had conceived a particular distaste for. It was, “Oh, Ben, if you love me, back her!”

Resolution. The narrator explicitly states his lesson learned at the end of the story and adds a detail about his continuing humiliation.

Discussion Questions

- For what reason might Twain have chosen to tell this anecdote in his memoir?

- How does telling this story help Twain reveal his experience of learning to be a riverboat pilot?

- How does Twain build tension to support the conflict in the anecdote?

- How does the narrator pull the reader into the action in the paragraph beginning “But that did the business for me”?

- How do the narrator’s word choices in the story shape the tone and mood?

- How does Twain’s use of vivid details and descriptions help the reader connect to the text?