2.4: Annotated Sample Reading from The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois

- Page ID

- 134139

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Articulate how conventions are shaped by purpose, language, culture, and expectation.

- Analyze relationships between ideas and patterns of organization.

- Analyze how W. E. B. Du Bois uses language, identity, and culture to shape his writing.

Introduction

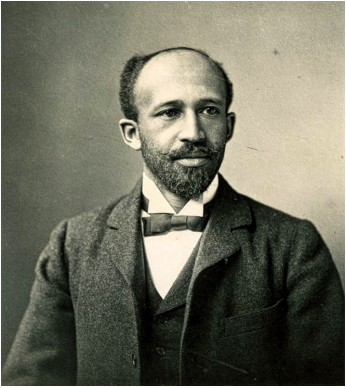

Figure \(2.5\) W. E. B. Du Bois (credit: “Du Bois, W. E. B..” Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) was an American historian and sociologist who graduated from Fisk University in 1888 and Harvard University in 1895. Du Bois deeply influenced the civil rights movement in the United States and is widely regarded as among the most important Black protest leaders and activists of the first half of the 20th century. He helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and his essay collection The Souls of Black Folk (1903) is considered seminal American literature.

Du Bois conducted sociological investigations of Black life in America, specifically the disenfranchisement of Black Americans and the pervasive nature of racism, including how it can influence how people of color see themselves. Du Bois dedicated years of his life to sociological studies of Black people in America, at first applying social science in his quest for racial and social justice. However, he eventually came to believe that the only path to progress was through protest. In his written works, particularly The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois discusses the dual nature of living as a Black person in America and feeling unable to be both a “Negro” and an American at once. In the excerpt below, Du Bois explains his famed theories of the color line, the veil, and double consciousness.

Du Bois’s work was a direct result of the world in which he lived and the one from which previous generations came—one that highlighted the complex issues of race and conflict in America. He wrote both for Black and White audiences, professing that his message was for all and affected the very heart of American democracy. Learning about the struggles of Black people in 19th- and early 20th-century America is still important today, and even a century later, Du Bois’s words can help all people understand the complex contextual issues that affect race relations. Understanding these challenges encourages tolerance, acceptance, and connections between cultures.

Living By Their Own Words

Between Me and the World

Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it.

All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying directly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know an excellent colored man in my town; or, I fought at Mechanicsville; or, Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil? At these I smile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.

The Color Line. Du Bois previously introduced the “color line,” the divide between races, in his “Forethought.” This line is sometimes invisible, but at other times, it is a physical line. The example of White people wondering what it feels like to be “a problem” demonstrates the invisible color line separating Black and White citizens into two separate communities.

Audience. Du Bois probably is writing with a White audience in mind, as Black readers likely understand the ideas he proposes. He uses academic language, which may be his authentic voice as an academic and a writer, but he also seeks to reach his intended audience.

And yet, being a problem is a strange experience,—peculiar even for one who has never been anything else, save perhaps in babyhood and in Europe. It is in the early days of rollicking boyhood that the revelation first bursts upon one, all in a day, as it were. I remember well when the shadow swept across me. I was a little thing, away up in the hills of New England, where the dark Housatonic winds between Hoosac and Taghkanic to the sea. In a wee wooden schoolhouse, something put it into the boys’ and girls’ heads to buy gorgeous visiting-cards—ten cents a package—and exchange. The exchange was merry, till one girl, a tall newcomer, refused my card,—refused it peremptorily, with a glance. Then it dawned upon me with a certain suddenness that I was different from the others; or like, mayhap, in heart and life and longing, but shut out from their world by a vast veil.

The Veil. Du Bois’s anecdote about the girl refusing his card introduces his idea of the “veil,” a symbol he uses throughout the text to demonstrate the color line. The veil represents the different worlds that Black and White people must inhabit. Though invisible, the veil shuts Du Bois out of this girl’s world.

I had thereafter no desire to tear down that veil, to creep through; I held all beyond it in common contempt, and lived above it in a region of blue sky and great wandering shadows. That sky was bluest when I could beat my mates at examination-time, or beat them at a foot-race, or even beat their stringy heads. Alas, with the years all this fine contempt began to fade; for the words I longed for, and all their dazzling opportunities, were theirs, not mine. But they should not keep these prizes, I said; some, all, I would wrest from them. Just how I would do it I could never decide: by reading law, by healing the sick, by telling the wonderful tales that swam in my head,—some way. With other black boys the strife was not so fiercely sunny: their youth shrunk into tasteless sycophancy, or into silent hatred of the pale world about them and mocking distrust of everything white; or wasted itself in a bitter cry, Why did God make me an outcast and a stranger in mine own house? The shades of the prison-house closed round about us all: walls strait and stubborn to the whitest, but relentlessly narrow, tall, and unscalable to sons of night who must plod darkly on in resignation, or beat unavailing palms against the stone, or steadily, half hopelessly, watch the streak of blue above.

Point of View and Voice. Du Bois uses the first-person point of view to relate his lived experiences. He writes in a voice that invites readers to picture him speaking, asking rhetorical questions.

Vivid Language. Du Bois uses vivid language to emphasize the bitterness created by the treatment of Black children. The image of the “prison-house” walls closing in shows the inability to escape the veil that society placed between White and Black children. Du Bois emphasizes the impact of this separation in the choice that Black children must make: accept that they will never have the opportunities enjoyed by White children or hopelessly try to achieve them.

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

Double Consciousness. Du Bois expands the image of the veil separating the worlds of Black and White people to include the idea of “double-consciousness”: that Black people see themselves through the eyes of White people. Racist ideation is inescapable, and Black people end up viewing their own culture negatively.

Conflict. These ideas of double consciousness and the veil leave Black Americans at war with themselves. Du Bois uses the metaphor of a measuring tape meant for one world but used to measure another and the warring idea of “twoness.”

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife,—this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.

Culture and Self. Du Bois explores the concept of self through the lens of Africanism and Americanism. He recognizes that the “Negro soul” has an important place in the world. Yet he feels that holding on to his Black roots means that the world sees him as un-American and leaves him without opportunity

This, then, is the end of his striving: to be a co-worker in the kingdom of culture, to escape both death and isolation, to husband and use his best powers and his latent genius. These powers of body and mind have in the past been strangely wasted, dispersed, or forgotten. The shadow of a mighty Negro past flits through the tale of Ethiopia the Shadowy and of Egypt the Sphinx. Through history, the powers of single black men flash here and there like falling stars, and die sometimes before the world has rightly gauged their brightness. Here in America, in the few days since Emancipation, the black man’s turning hither and thither in hesitant and doubtful striving has often made his very strength to lose effectiveness, to seem like absence of power, like weakness. And yet it is not weakness,—it is the contradiction of double aims.

Simile. The comparison of Black men to falling stars, never allowed to reveal the possibilities of their success, demonstrates the difficulties they face.

Discussion Questions

- What might have been the impact of Du Bois’s use of academic language on his audience?

- How does Du Bois use his personal experience to relate the experiences of a broader culture?

- What impact do the images of shadows and darkness have on Du Bois’s message?

- In this section of the text, Du Bois focuses on internalization of race. How does this concept illustrate the impact of racism on society?

Assumptions and Stereotypes

Du Bois experiences the veil between worlds as a Black American because of assumptions and stereotypes. Unfortunately, such assumptions and stereotypes still exist in America today. In Chapter 2, you have begun to learn about the impact of language on culture and about how developing anti-racist and inclusive ideas is an important part of the composition process.