2.3: Glance at the Issues- Oppression and Reclamation

- Page ID

- 134138

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Articulate how language conventions shape and are shaped by readers’ and writers’ practices and purposes.

- Define oppression and explain its effects.

- Define inclusion and summarize ways to write inclusively.

Writing about identity and culture gives authors the opportunity to share personal experiences and provides a vehicle for storytelling. This storytelling can turn into a purposeful message with meaningful rhetorical impact.

What is Oppression?

Some languages, cultures, and identities face discrimination. People often believe that for one group to advance, another must be held back. This suppression of growth, advancement, economic development, and educational opportunity has led to systems of oppression—prolonged and sustained unjust treatment—for some groups. For example, Black people from various parts of Africa endured centuries of oppression because of the transatlantic slave trade. Between the mid-16th and mid-19th centuries, European, Spanish, and American groups captured an estimated 10–12 million African men, women, and children from their homelands, boarded them on ships, and transported them to Europe, the Caribbean, and the Americas to be sold into enslavement. After 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in the United States, Black people continued to be denied basic human rights, such as the opportunity to work at certain jobs, despite their educational achievement; to be served a meal in a restaurant; to use a public restroom or water fountain; to shop for necessities in a grocery or department store; or to live peacefully in their own communities. Black Americans have continued to be subjected to social inequities. As a community, they suffer from higher rates of incarceration, lower pay rates, fewer educational opportunities, and higher mortality at the hands of law enforcement—injustices that stem from racist policies of centuries past. Similarly, Indigenous people have been subjected to hundreds of years of oppression and silencing, often the result of colonialization, which included stripping them of their customs, land, language, and lives.

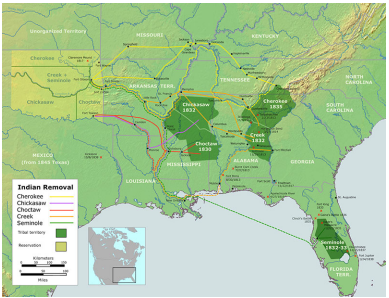

Figure \(2.4\) This map shows the routes of the Trail of Tears (https://openstax.org/r/trailoftears) (1836–1839), the U.S. government’s forced relocation of tens of thousands of Native Americans from their lands in the southeastern United States to “Indian Territory” in what is now Oklahoma. Thousands died of starvation, exposure, or disease during the long and brutal 1,200-mile journey, much of it on foot. (credit: “Trails of Tears” by Nikator and www.demis.nl/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Oppression isn’t just a historical problem—it extends to society today. In the two decades since the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States and the subsequent War on Terror, Muslims and Sikhs have experienced hate crimes and oppression. People who identify as LGBTQ have been shunned or persecuted, subjected to hate crimes, and banned from serving in the military and have struggled to gain the right to marry. This TED Talk (https://openstax.org/r/thistedtalk) highlights the struggle for transgender rights.

In addition, migrant and refugee families, largely from countries in Central and South America, have been separated and jailed in recent efforts to curtail immigration along the southern U.S. border. Asian Americans have been subjected to racially motivated harassment and attacks, heightened by the COVID-19 pandemic, including the violent March 2021 mass shooting at an Asian American massage parlor. This TED Talk (https://openstax.org/r/talksstereotype) discusses the harm of Asian stereotypes. Discrimination has persisted for generations and continues to make it difficult for those who oppress to view the oppressed as their equals.

Reclaiming Humanity

One way to help restructure the world to reduce or even eliminate oppression is to explore your own biases. A bias occurs when you prejudicially favor one person, place, thing, or idea over another

People are naturally conditioned to favor the familiar over the unfamiliar. If you begin to question why you think as you do or make the decisions you make, you may begin to view others as equal, even though they may look different, live differently, and experience the world differently.

Two of the most frequent ways people isolate others are through markers of identity, especially race and gender, and through language varieties, such as standard and nonstandard English. If your view of people is primarily influenced by their physical features and the words they speak, you do not allow yourself to engage fully with them in their humanity.

Viewing others as people first and understanding the importance of questioning the lens through which you view them is the beginning. However, you also have to think critically about language bias. When you hear people of African descent speak in African American Vernacular English (AAVE) or speak English with Caribbean or African accents, you may make assumptions about who they are and what they know. When you encounter people who speak English with Spanish accents, you also may make assumptions about who they are and their place in the world. However, when you hear British English or English spoken with a French, German, or Slavic accent, you may notice the difference, but you also may make a different set of assumptions about those people.

Anti-racism as Inclusion

One way to be inclusive is to write in specifically anti-racist ways. Inclusive writing begins with identifying ways in which language can be and has been used to exclude cultures, social groups, or races.

Exclusive language is, unfortunately, ingrained in much of academia. It is a product of habit and the assumption that all readers are alike, with similar experiences, values, and beliefs. To write inclusively, think beyond yourself by considering other perspectives, groups, and races that may be harmed by thoughtless word choices.

Here are several principles to help you develop inclusive and anti-racist writing:

- Consider the assumptions you make about readers, and then work to address those assumptions.

- Choose language carefully.

- Revise with a critical eye. Look for racist phrases and words that label cultures negatively.

- Seek feedback and receive it with an open mind primed for learning. Because writing is personal, you may easily feel offended or dismissive. However, feedback, especially from people whose perspective differs from yours, can help you grow in anti-racist knowledge.

- Consider rhetoric and presentation. Aim to make your writing understandable, straightforward, and accessible. Use a glossary or footnotes to explain complex terms or ideas.

- Avoid casual phrases that suggest people with disabilities or from other cultures are victims and avoid euphemisms that refer to cultures to which you do not belong. Similarly, avoid using mental health issues in metaphors.

- Think about your adjectives. Some groups or people prefer not to be described by an adjective. It is important to follow individual groups’ preferences for being referred to in either person-first or identity-first language.

- Avoid stereotyping; write about an individual as an individual, not as if they represent an entire group or culture. You may also choose to use gender-neutral pronouns.

- Be precise with meaning. Rather than describing something as “crazy,” try a more precise term such as intense, uncontrolled, or foolish to give a more accurate description.

- Impact overrules intent. The impact of your language on your reader is more important than your good intentions. When you learn better, do better.

Exploring Issues

The following key terms and characteristics provide a better understand of anti-racist and inclusive writing:

- Ally: a person who identifies as a supporter of marginalized groups and who advocates for them

- Anti-racist: adhering to a set of beliefs and actions that oppose racism and promote inclusion and equality of marginalized groups

- Critical race theory: the idea that racism is ingrained in the institutions and systems of American society

- Cultural appropriation: taking the creative or artistic forms of a different culture and using them as one’s own, particularly in a way that is disrespectful of the original context

- Culture: the shared beliefs, values, and assumptions of a group of people

- Emotional tax: the invisible mental stress taken on by people of marginalized backgrounds in an attempt to feel included, respected, and safe

- Ethnocentrism: the idea that one’s own culture is inherently better than other cultures

- Intersectionality: the intertwining of different aspects of social identities, including gender, race, culture, ethnicity, social class, religion, and sexual orientation, that results in unique experiences and opportunities

- Microaggression: behavior or speech that subtly or indirectly expresses prejudice based on race, gender, ability, age, or other aspects of identity, often but not always without an individual’s conscious intention (For example, the drill team director instructs all members to wear their hair straight for competition.)

- Neurodiversity: the idea that humans have a range of differences in neurological functioning that should be respected

- Unconscious bias: any implicit, unfair preferences that people hold without being aware of them