11.2: Annotation

- Page ID

- 120090

Listen to an audio version of this page (8 min, 27 sec):

Why annotate?

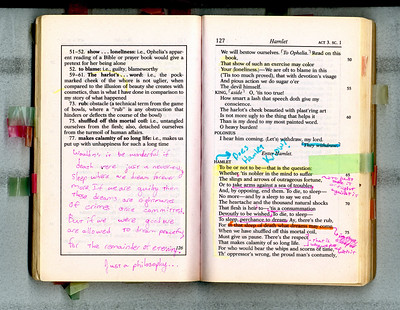

Writing notes can make reading more enjoyable. Reading doesn't have to be passive; we can find our own voices as we begin a conversation with the text. As a step in the writing process, annotation can be invaluable. As we have seen in this book, most college writing assignments ask us to respond to other arguments. e don't have to pull our ideas out of thin air. Early in the writing process, we can get ideas by rereading and making notes on any text we are going to write about. These notes will help us come up with specific points to make in our essay. We may even be able to copy and paste whole sentences of annotation into an essay first draft.

Annotate to engage

Annotating can help us stay focused on, and emotionally and intellectually connected to, what we are reading. It suggests that we feel empowered to speak back to the text.

| What we might do or think | What we might write |

|---|---|

|

Respond to the text emotionally |

"Inspiring :-) Discouraging :-(" |

|

Relate to the text |

"Ref. Psych Prof. point about anxiety" "Me in 9th grade" |

|

Visualize information or concept |

Doodle or draw a picture to remind yourself quickly. |

|

Ask questions |

"How does this compare to middle-class students?" |

| Agree or disagree with the author | "Disagree (with the opinion he just described)" |

|

Predict what is coming next |

"I think the character will...." |

|

Connect with other knowledge |

"Different cause/effect than Wise describes" |

Annotate to understand

As we saw in Section 2.3: Making Notes on the Writer's Claims, paraphrasing the points next to the text can help us understand fully. It can also help us prepare to write a summary, as we saw in Chapter 3. Noting any difficulties we have with understanding can remind us to ask or research the question later, and it can also get our minds working on solving the problem.

| What we might do or think | What we might write |

|---|---|

|

We don’t understand a word or term, so we go back and reread the sentence and figure it out – or look it up. |

Circle the word, and, after we figure out its meaning, write the meaning next to the word. |

|

We don’t understand a word, but realize we can keep reading and still understand. |

Circle the word and look it up later. |

|

We don't understand what the author is saying as it applies to a particular situation. |

Write your question next to the text and bring it up in class or with a tutor. |

|

You find the sentence that seems to be the main idea of a paragraph. |

Underline and paraphrase it briefly. |

|

You don’t see the main point actually written there, but you know what it is. |

Paraphrase it. |

|

The author says she has three reasons for her point, so you decide to make sure you can find all three. |

Write “3 reasons” in the margin, and underline and number the reasons – 1, 2, 3 – when you find them. |

|

We notice that several points serve as examples for a claim. |

Underline them and write “ex” and draw an arrow to the point that the example is supporting. |

Annotate to assess, respond, and compare

If we are going to write an assessment of the text as we discussed in Chapter 4 or an original response as we discussed in Chapter 5, annotating can help us get started. We can note any possible strengths and weaknesses in the argument so we can later reflect more fully on the argument's validity. Often these notes about possible strengths and weaknesses will point us toward our own original responses, suggestions, or counterarguments.

|

What we might do or think |

What we might write |

|---|---|

|

Question the evidence presented in the text. |

"This seems like an isolated case. I don't think it's typical." |

|

Think of a counterargument. |

"What about the argument that Universal Basic Income encourages people to be entrepreneurs because they don't have to worry about just getting by?" |

|

Think of additional evidence, examples, stories, or personal experiences that support the author’s argument. |

"This rings true because I've seen it so often among my relatives." |

|

Think of other texts that advance the same or similar arguments. |

"Similar to Plato's idea that the truth is absolute but we can only glimpse it through shadows." |

Annotate to find evidence

Once we have an essay assignment, a topic, or an outline, we may know more specifically what it is we need from the text. We can take notes specifically for the purpose of identifying points or quotations to incorporate in an essay.

| What we might do or think | What we might write |

|---|---|

|

You find a statistic showing that more first generation students than ever are going to college. |

Underline the statistic and write "1st gen population > ever" |

|

You find a quote or detail that supports the idea that wages of people of color were rising in the '60s due to affirmative action. |

Underline it and write, "aff. action 60s ups wages" |

Tools and formats for annotation

- Underline or highlight words, sentences, and passages that stand out.

- Write notes by hand on the margins of the text.

- Consider using differently colored pens or highlighters to make the notes stand out or to identify different kinds of notes.

- Attach post-it notes with comments to the text.

- Write a list of notes on a separate sheet of paper with the page numbers they refer to.

- If your source is electronic, use the highlighting and commenting functions available in many e-readers.

- If your source is a web page or PDF, use a digital annotation platform such as Hypothesis.

- Keep a reading journal where you reflect in full sentences or paragraphs.

- Keep a double-entry journal where you divide pages into two or more columns by the type of response. For example, in the first column you might include quotation or paraphrases and in the second, you might include your questions, opinions. Be sure to include the page number or link to the part of the reading you were referencing.

Attributions

Adapted by Anna Mills from "MLA In-Text Citations," included in Writing and Critical Thinking through Literature by Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap, ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative. Ringo and Kashyap cite "MLA In-Text Citations" as adapted from the following sources:

- English Composition 2, provided by Lumen Learning. CC BY-SA.

- Successful College Composition by Kathryn Crowther, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, and Kirk Swenson, provided by Galileo, Georgia's Virtual Library. CC-NC-SA-4.0.

- EDUC 1300: Effective Learning Strategies, provided by Lumen Learning. Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Writing for Success, provided by the Saylor Foundation. CC-NC-SA 3.0