8.4: Victorian art

- Page ID

- 67084

Victorian art

Artists responded to the wealth generated by empire and industry—and its moral consequences.

1837 - 1901

Early Victorian

Sir Edwin Landseer, Windsor Castle in Modern Times

by AMY ROBSON

A tribute to home, hearth and hounds

When one thinks of Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, RA, many accomplishments come to mind. An English animal painter of mainly horses, dogs, stags and lions, Landseer’s works became commonplace in the homes of Victorian audiences, and his Lion sculptures sit proudly in Trafalgar Square to this very day.

However, perhaps the most relatable Landseer artworks to our modern eye are those which depict the enduring relationship between the royal family and their dogs, a love affair which many modern pet owners can relate to. Windsor Castle in Modern Times presents such a scene and, as such, acts as a window into which we can explore both our love of Landseer and of dogs.

A conversation piece

Windsor Castle in Modern Times was modelled off a type of painting known as a ‘Conversation piece’—in which a group of people (normally family) would be positioned in an informal setting engaged in conversation, or a similar activity—and this painting by Landseer was certainly a discussion point among its royal patrons. Begun in 1840 and not finished until 1845, multiple sittings and bouts of time when Landseer appeared not to work on the painting at all meant that Queen Victoria was far from amused.

Despite this, when the painting was finally hung up in her sitting room in Windsor Castle, Queen Victoria determined with no hesitancy that the painting was a “very beautiful picture, & altogether very cheerful & pleasing.” And, when looking at the painting, it’s not hard to see why the final result was received so positively.

Regal but relatable

The painting depicts an encounter between Victoria and Albert, in a drawing room at Windsor Castle (a medieval castle at Windsor that Queen Victoria used as the principle royal residence), just after Albert has come back from a day out hunting. Triumphant in his endeavours, as can be seen from the game that is sprawled out across the room, Victoria greets Albert with the presentation of a small bouquet of flowers (known as a nosegay), whist their eldest child, Victoria, can be seen playing with a dead kingfisher. The scene is, of course, entirely manufactured for the conversation piece—game would not be spread out with such compositional intent in the drawing room, or spread out in the drawing room at all for that matter!—but this is a large part of the painting’s charm and success.

Shown in the traditional role of royal huntsman, Prince Albert appears as an appropriately masculine figure in the home, at the same time as also representing the virtues that came with embracing a countryside life in Industrial Britain. Meanwhile Queen Victoria is depicted as a loving and caring wife and the epitome of feminine virtue—greeting her husband when he comes home in the most delicate of manner; with a bouquet of flowers—but, her position, standing in front of Albert, also makes it clear that she is the ruling monarch.

All of these elements demonstrate the effectiveness of Landseer’s artwork—making the royal family look both regal, but also relatable in the eyes of the aspiring middle-class, who found themselves eager to emulate royal examples in this era. Completing the painting (and no doubt, a prevalent reason as to why Landseer was chosen to produce the work) is the inclusion of four dogs in the painting. Beloved family pets, each with their own story, the dogs in this painting add an additional level to Windsor Castle in Modern Times and, at the same time, also work to showcase Landseer’s reputation as the leading animal painter of the period.

Canine conversations

It was no secret that Queen Victoria was a lover of animals, and dogs in particular. When Landseer was given his first royal commission it was to paint Victoria’s beloved spaniel, Dash, when she was a Princess, for her Birthday. Windsor Castle in Modern Times follows Landseer’s transition into royal pet painter, and the animals in the painting are afforded as much detail as the royal family themselves.

The dog at the far bottom left of the painting, nearest to the young Victoria, was a Skye terrier (a breed the Queen favored) called Cairnach—who would also go on to be painted by Landseer in 1842 as a Christmas present from Albert to Victoria. If he wasn’t well known when Windsor Castle in Modern Times was finished then he would become so over time, as Albert’s Christmas present to Victoria was reproduced and made available to the public as an engraving. To the right of Cairnach, begging eagerly as he looks up to Albert, Islay can been seen; another Skye terrier and one of the Queen’s favorite dogs. He was, in fact, popular enough that he had been painted in a previous pet portrait by Landseer, titled Islay and Tico with a Red Macaw and two Love Birds (1839), in the exact same begging pose no less!

Meanwhile the ironically named Skye terrier, Dandy Dinmont, can be seen in the painting at Albert’s side, licking his hand in a faithful greeting. Dandy’s faithful depiction in this painting would not be the last either, as, in 1843, he would be painted by Landseer at the side of the new born Princess Alice, in a painting by the same name, as her faithful guardian.

The most well-known dog in this painting, however, would certainly be Eos, the Greyhound being stroked by Prince Albert. Eos was Albert’s favorite dog and belonged exclusively to him, rather than being a family dog.

This notable companion is best known for being the subject matter of the often reproduced Eos, A Favourite Greyhound, the property of H.R.H. Prince Albert (1841) by Landseer—an artwork which popularized the format of pet portraiture which followed (in pose, composition and the items included).

In the same year Landseer also painted Eos with the young Princess Victoria (titled Victoria, Princess Royal, with Eos), as a birthday present to Albert. Lying faithfully with the Princess, Eos is seen here as the loyal and endearing pet that she was received as by her master.

By the time this painting was finished, in 1845, both Eos and Islay had passed away, making their presence in this painting not just a dedication to man’s best friend, but also a tribute to two beloved family pets.

What does this tell us?

Victorian Britain saw a notable boom in both dog ownership and dog portraiture, as dogs shifted from working and sporting animals to family pet, and this boom was certainly influenced by the royal family’s love of dogs. With both more time and money at their disposal, the newly developing middle-class found a hobby in both the owning and showing of dogs, with the Queen’s love of the animal enabling a feeling of distinction in the act, which (on the other side of the coin) also served to make the royal family seem more relatable.

As such we can see how Windsor Castle in Modern Times was truly a tribute to home, hearth and hounds—effectively presenting the royal family to those who wished to follow in their example, both in moral values and in animal preferences, but also giving Queen Victoria a memorable image of her family as she wished to see it; dogs and all.

Additional resources:

This painting in the Royal Collection

This painting on the website for Michelle Facos’s An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art

The Conversation Piece: Scenes of Fashionable Life, the Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh (review in The Telegraph)

Charles Barry and A.W.N. Pugin, Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament)

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Charles Barry and A.W.N. Pugin, Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament), 1840-70, London

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Robert Smirke, The British Museum

by BEN POLLITT

A museum open to all studious and curious persons

In terms of painting, Europe was most definitely leading the way, the Louvre first opening its doors to the public in 1793, granting access to the French royal family’s former collection of art. In England, on the other hand, public access to works of art was largely a private enterprise. The Egyptian Hall in London’s Pall Mall being a good example. With its evocative neo-Egyptian façade, it was here Géricault exhibited his The Raft of the Medusa in 1820 and at other times large-scale works by important British painters such as Turner were on display, always to a paying audience (a shilling). It was not until the opening of the National Gallery in 1824, over thirty years after the Louvre, that the British had an art collection that belonged to the public and which they were free to visit.

While lagging behind in some ways, in others London was somewhat ahead of the rest. It was here, for example, that the first public museum in the world was opened. The British Museum, was established in 1753 and open, free of charge “to all studious and curious Persons.” Well, in actual fact, there were quite stringent conditions for entry, being closed four days a week and all of August and September too. Then when it was open, visitors needed to apply for a ticket and present a letter of recommendation, while women, for propriety’s sake, were only admitted in pairs.

The Museum, in its first incarnation, was located in a grand mansion on Montague Street, the site of the present building. Along with books and manuscripts, its collection held some 80,000 objects of natural history and “man-made curiosities,” all of which were bequeathed to the nation by the Royal Physician and chocolatier Hans Sloane, among them a very old flint hand axe found near the bones of a massive elephant buried in the gravel on Gray’s Inn Lane. While it is very doubtful those first curious and studious persons who entered the museum could conceivably have guessed its true date at 350,000 years or that massive elephants roamed the country back in the Stone Age, the questions such objects raised were absolutely fundamental to the emergence of new sciences in the nineteenth century, such as archaeology, anthropology, geology and paleontology.

Two other acquisitions that helped secure the Museum’s international reputation were the Rosetta Stone (1802) and the Parthenon sculptures (1816). By 1823, when George IV gifted a library of 60,000 books he had inherited from his father, the Montague House site was no longer large enough to hold it all.

One of the greatest neoclassical interiors in London

The commission for the new building was given to Robert Smirke, a well-established neoclassical architect. The building took around thirty years to complete, its elevation mirroring the expanse of the British Empire itself. He started with the east wing, built to house the King’s Library. It survives complete today and is considered one of the greatest neoclassical interiors in London.

In 1827 construction on the remaining wings was begun, creating the famous quadrangle with its impressive colonnaded portico and two acre courtyard. The antique sourcing of the façade is predictable enough. Neoclassicism had been the prevailing fashion in European architecture since the 1750s and would have seemed an appropriate choice, especially given the number and quality of classical sculptures in the Museum (particularly the Parthenon sculptures).

These must surely have influenced Smirke’s design of the main entrance, which is modeled on Greek temple design and shares the same number of eight columns as the Parthenon itself. In scale though it is almost double the size, while the austere Doric order is replaced by the based and slender columns and scrolled capitals of the ionic order, which, with all its connotations of wisdom and learning, must have been thought best suited for the building’s purpose.

The entablature (the entire horizontal area carried by the columns) is composed of a tripartite architrave (the lowest part of the entablature) with a blind frieze above (without sculptural decoration) and a dentilated cornice (dentils are the repeated blocks forming a pattern at the base of the cornice)—all running in an unbroken chain around the whole length of the south portico.

The building is topped with a flat roof, the pediment therefore being false, in the sense that its function is decorative rather than structural, its pinnacle creating a vertical axis that bisects the main entrance way. The projecting wings, like the skene or scenic backdrop in an ancient Greek theatre, add a dramatic sweep to the façade, channeling the eye of the viewer to the main entrance.

The conscious reworking of the classical language of architecture, drawing on a period which, according to enlightened tastes, marked the greatest flowering of art and culture in European history, obviously served to elevate the status of the building, expressing something of the pride and confidence of the British at the very heyday of their empire. While not necessarily equating Britain with Rome or Greece, the building did seem to suggest, firstly, that the British were carrying the torch of civilization and, secondly, that they, like the Romans and the Greeks before them, were up to the task.

This explicit nationalist message is illustrated in the pediment sculptures, designed by Richard Westmacott and given the grandiose name, The Rise of Civilisation. Here we see a female Britannia-like figure representing Enlightenment, surrounded by other allegorical figures standing for various artistic and scientific disciplines.

To the far left, however, we find a different story. Here early man emerges, crawling from rubble to be handed the Lamp of Knowledge by the Angel of Enlightenment, behind him is a dog-like animal and behind that a crocodile. Though hard to pick out from ground level, that crocodile’s snout is one of the most telling details in the whole sculpture, offering a foretaste of the debates that were soon to rage between religious and scientific communities. Though Darwin had yet to publish his On the Origin of Species, with the type of fossil and geological evidence that the Museum was amassing, the case for evolution was certainly mounting.

New technologies

Although on the face of it, the Museum might seem to be a very conservative building, the manner in which it was constructed was anything but. Smirke, for instance, was one of the first architects to make extensive use of concrete, laying it as a base for the cast iron frame that underpins the entire structure, a frame that was then filled with London stock brick and covered in a facing of Portland stone, brought all the way from Dorset.

In the design of the interior, too, which was overseen by Smirke’s brother, Sydney from 1845 onwards, British materials were used throughout, the floor of the entrance hall—the Weston Hall—being paved with York stone, the staircase balustrade and ornamental vases carved from Huddlestone stone and the sides of the Grand Staircase lined with red Aberdeen granite. While, the fact that these materials were all sourced from the British Isles reinforced the nationalist message, the vivid colours of the stones themselves created a luminous interior that was further adorned with colorful designs based on those found on classical buildings, which by the nineteenth century were known to be polychromatic. The original stonework has all survived to this day, while the 1847 painting and gilding was restored in 2000. The electric lamps in the hall are also replicas of the original, installed in 1879, making the Museum one of the first public buildings in London to be electrically lit.

The Reading Room

By the 1850s, with the collection continuing to expand, the site needed a yet larger library, the idea this time being to construct a round room in the central courtyard. Designed by Sydney Smirke, the Reading Room was built between 1854-1857. Given the size of it, 42.6m in diameter, the speed of construction, even assisted by modern building techniques, was astounding. Using cast iron, concrete and glass, it was a masterpiece of nineteenth-century technology, inspired as much by Paxton’s ferrovitreous Crystal Palace as by the Pantheon in Rome; the airy and graceful internal dome disguising the complex fretwork of cast iron that supported it from without. Even the bookshelves were state-of-the-art, built of iron to carry the weight of the books and making up a staggering three miles of cases and twenty-five miles of shelving.

Recent times

This was not the end of the story, though. In 1997, the books were relocated yet again to the newly built British Library on Euston Road and the old Reading Room transformed into an exhibition space, a move that provided the catalyst to revitalize the old courtyard. In 2000, Foster and Partner’s Queen Elizabeth II Great Court was opened and the two buildings, the Museum and the Reading Room, were now connected with a huge glazed canopy spanning the two acres of the courtyard. And the story still continues, for even more recently yet more changes have been made, with the new World Conservation and Exhibitions Centres, designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partners, open in 2014.That the site is a constantly evolving one is only to be expected, given the ever-changing nature of the collection itself. An astonishing compendium of 260 years of human discoveries, the British Museum is indeed a house filled with many mansions, the outside of which, in the last analysis, however brilliant and varied in its construction it may be, will never come close to matching the glories within.

Additional resources:

General history of the British Museum

History of the British Museum collection

The Grey’s Inn handaxe and the birth of archaeology

Diagram showing a column, with an entablature above, including a frieze and cornice

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Pre-Raphaelites and mid-Victorian art

The era of Darwin, Tennyson, Dickens, labor laws, the Pre-Raphaelites and the Arts and Crafts movement.

c. 1848 - 1870

A beginner's guide

A beginner’s guide to the Pre-Raphaelites

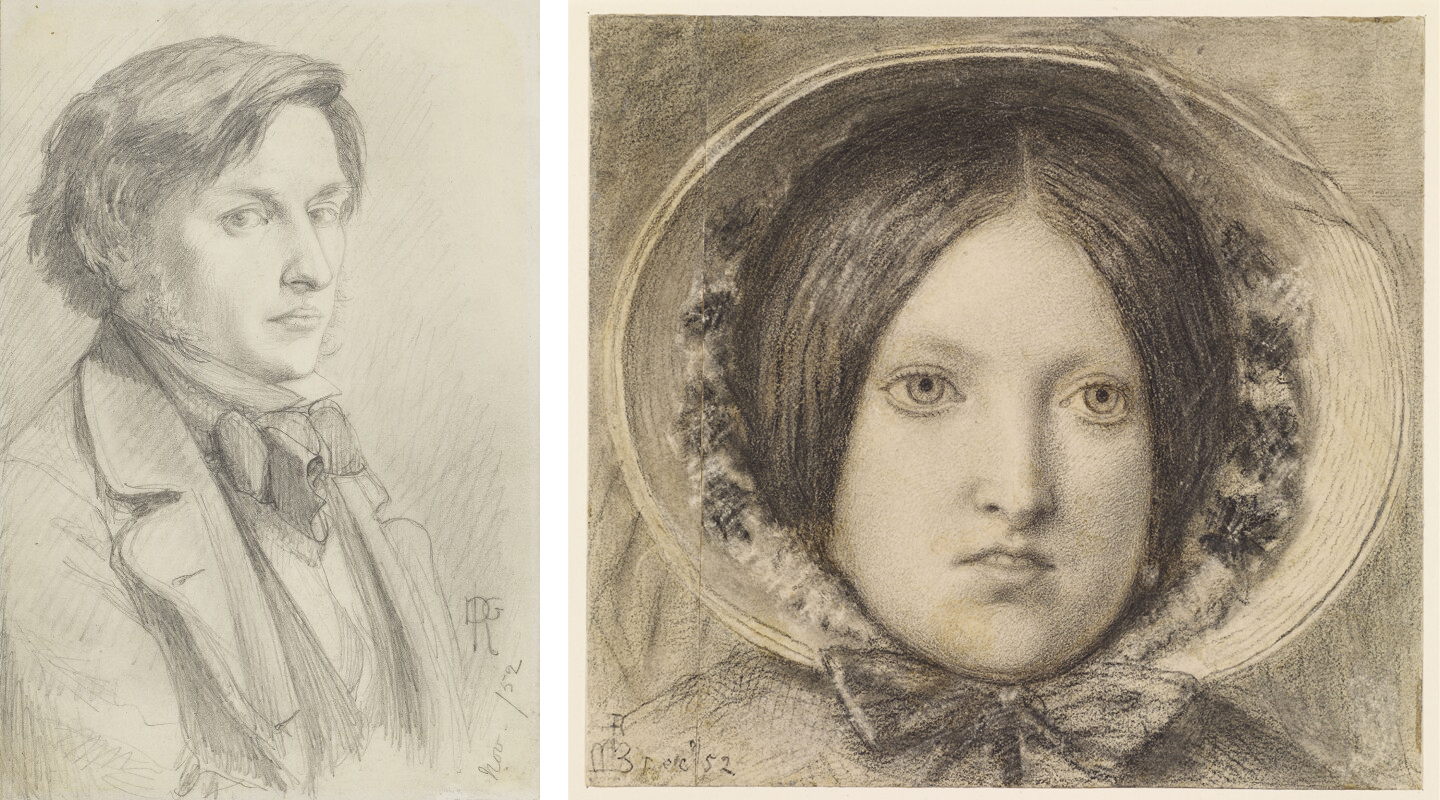

At first they were three

During a visit to the Royal Academy exhibition of 1848, the young artist and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti was drawn to a painting entitled The Eve of Saint Agnes by William Holman Hunt. As a subject taken from the poetry of John Keats was a rarity at the time, Rossetti sought out Hunt, and the two quickly became friends. Hunt then introduced Rossetti to his friend John Everett Millais, and the rest, as they say, is history. The trio went on to form the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group determined to reform the artistic establishment of Victorian England.

Looking back to look forward

The name “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood” (PRB) hints at the vaguely medieval subject matter for which the group is known. The young artists appreciated the simplicity of line and large flat areas of brilliant color found in the early Italian painters before Raphael, as well as in 15th century Flemish art. These were not qualities favored by the more academic approach taught at the Royal Academy during the mid 19th century, which stressed the strong light and dark shading of the Old Masters. Another source of inspiration for the young artists was the writing of art critic John Ruskin, particularly the famous passage from Modern Painters telling artists “to go to nature in all singleness of heart . . . rejecting nothing, selecting nothing and scorning nothing.” This combination of influences contributed to the group’s extreme attention to detail, and the development of the wet white ground technique that produced the brilliant color for which they are known. The artists even became some of the first to complete sections of their canvases outdoors in an effort to capture the minute detail of every leaf and blade of grass.

And then they were seven

It was decided that seven was the appropriate number for a rebellious group and four others were added to form the initial Brotherhood. The selection of additional members has long mystified art historians. James Collinson, a painter, seems to have been added due to his short-lived engagement to Rossetti’s sister Christina rather than his sympathy with the cause. Another member, Thomas Woolner, was a sculptor rather than a painter. The final two members, William Michael Rossetti and Frederic George Stephens, both of whom went on to become art critics, were not practicing artists. However, other young artists such as Walter Howell Deverell and Charles Collins embraced the ideals of the PRB even though they were never formally elected as members.

The P.R.B. goes public

The Pre-Raphaelites decided to make their debut by sending a group of paintings, all bearing the initials “PRB”, to the Royal Academy in 1849. However, Rossetti, who was nervous about the reception of his painting The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, changed his mind and instead sent his painting to the earlier Free Exhibition (meaning there was no jury as there was at the Royal Academy). At the Royal Academy, Hunt exhibited Rienzi, the Last of the Tribunes, a scene from an historical novel of the same name by Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Millais exhibited Isabella, another subject from Keats, created with such attention to detail that one can actually see the beheading scene on the plate nearest the edge of the table, which echoes the ultimate fate of the young lover Lorenzo in the story. In both paintings, the accurately designed medieval costumes, bright colors and attention to detail produced criticism that the paintings mimicked a “mediaeval illumination of the chronicle or the romance” (Athenaeum, 2 June 1849, p. 575). Interestingly, no mention was made of the mysterious “PRB” inscription.

Critical reaction

In 1850, however, the reaction to the PRB was very different. By this time, many people knew about the existence of the supposedly secret society, in part because the group had published many of their ideas in a short-lived literary magazine entitled The Germ. Rossetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domini appeared at the Free Exhibition along with a painting by his friend Deverell entitled Twelfth Night. At the Royal Academy, Hunt’s A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Priest from the Persecution of the Druids and Millais’s Christ in the House of his Parents, famously abused by Charles Dickens, received the brunt of the criticism. In the aftermath of the humiliating reception of their work, Collinson resigned from the group and Rossetti decided never again to exhibit publicly.

Ruskin to the rescue

Undeterred, Millais and Hunt again continued to exhibit paintings demonstrating the beautiful colors and detail orientation of the mature style of the PRB. The Royal Academy of 1851 included Hunt’s Valentine Rescuing Sylvia, and three pictures by Millais, Mariana, The Woodman’s Daughter, and The Return of the Dove to the Ark as well as Convent Thoughts by Millais’s friend Charles Collins. Although many were still dubious about the new style, the critic John Ruskin came to the rescue of the group, publishing two letters in The Times newspaper in which he praised the relationship of the PRB to early Italian art. Although Ruskin was suspicious of what he termed the group’s “Catholic tendencies,” he liked the attention to detail and the color of the PRB paintings. Ruskin’s praise helped catapult the young artists to a new level.

The dissolution of the PRB

The Brotherhood, however, was slowly dissolving. Woolner emigrated to Australia in 1852. Hunt decided in January 1854 to visit the Holy Land in order to better paint religious pictures. And, in an event Rossetti described as the formal end of the PRB, Millais was elected as an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1853, joining the art establishment he had fought hard to change.

Lasting impact

Despite the fact that the Brotherhood lasted only a few short years, its impact was immense. Millais and Hunt both went on to establish important places for themselves in the Victorian art world. Millais was to go on to become an extremely popular artist, selling his art works for vast sums of money, and ultimately being elected as the President of the Royal Academy. Hunt, who perhaps stayed most true to the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic, became a well-known artist and wrote many articles and books on the formation of the Brotherhood.

Rossetti became a mentor to a group of younger artists including Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, founder of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Rossetti’s paintings of beautiful women also helped inaugurate the new Aesthetic Movement, or the taste for Art for Art’s Sake, in the later Victorian era.

To a contemporary audience, the Pre-Raphaelites may appear less than modern. However, in their own time the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood accomplished something revolutionary. They were one of the first groups to value painting out-of-doors for its “truth to nature,” and their concept of banding together to take on the art establishment helped to pave the way for later groups. The distinctive elements of their paintings, such as the extreme attention to detail, the brilliant colors and the beautiful rendition of literary subjects set them apart from other Victorian painters.

Additional resources:

The Pre-Raphaelites on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Series of videos on the Pre-Raphaelites from the Tate

William Holman Hunt’s The Eve of St. Agnes from the Google Art Project

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

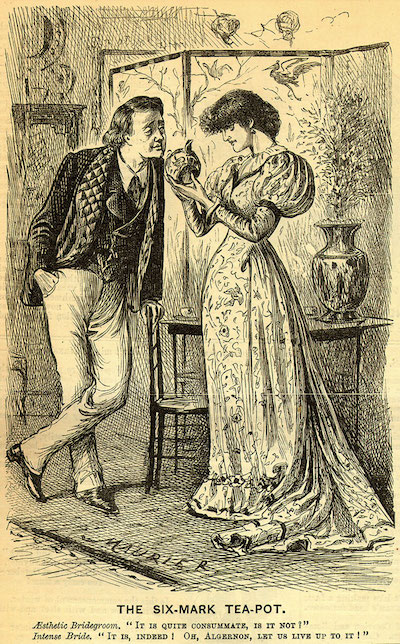

The Aesthetic Movement

Art for the sake of art

The Aesthetic Movement, also known as “art for art’s sake,” permeated British culture during the latter part of the 19th century, as well as spreading to other countries such as the United States. Based on the idea that beauty was the most important element in life, writers, artists and designers sought to create works that were admired simply for their beauty rather than any narrative or moral function. This was, of course, a slap in the face to the tradition of art, which held that art needed to teach a lesson or provide a morally uplifting message. The movement blossomed into a cult devoted to the creation of beauty in all avenues of life from art and literature, to home decorating, to fashion, and embracing a new simplicity of style.

In literature

In literature, aestheticism was championed by Oscar Wilde and the poet Algernon Swinburne. Skepticism about their ideas can be seen in the vast amount of satirical material related to the two authors that appeared during the time. Gilbert and Sullivan, masters of the comic operetta, unfavorably critiqued aesthetic sensibilities in Patience (1881). The magazine Punch was filled with cartoons depicting languishing young men and swooning maidens wearing aesthetic clothing. One of the most famous of these, The Six-Mark Tea-Pot by George Du Maurier (left) published in 1880, was supposedly based on a comment made by Wilde. In it, a young couple dressed in the height of aesthetic fashion and standing in an interior filled with items popularized by the Aesthetes—an Asian screen, peacock feathers, and oriental blue and white porcelain—comically vow to “live up” to their latest acquisition.

In the visual arts

In the visual arts, the concept of art for art’s sake was widely influential. Many of the later paintings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, such as Monna Vanna (above), are simply portraits of beautiful women that are pleasing to the eye, rather than related to some literary story as in earlier Pre-Raphaelite paintings.

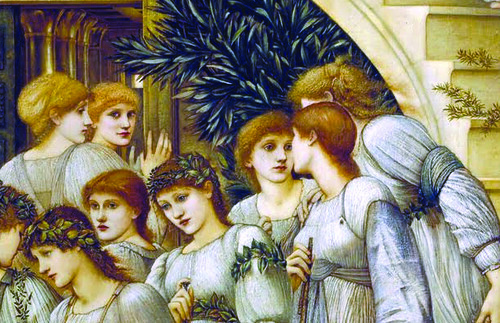

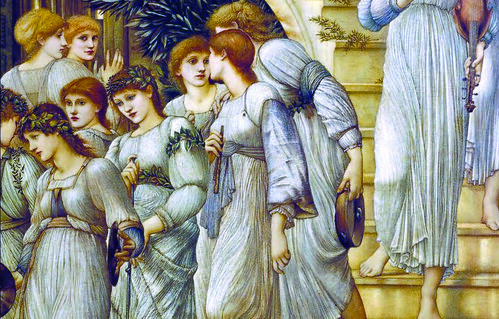

A similar approach can be seen in much of the work of Sir Edward Burne-Jones, whose The Golden Stairs (1880) captures the aesthetic mood in its presentation of a long line of beautiful women walking down a staircase, devoid of any specific narrative content. The designer William Morris, another disciple of Rossetti, created beautiful designs for household textiles, wallpaper, and furniture to surround his clients with beauty.

“flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”

Most famous of the aesthetic artists was the American James Abbott McNeill Whistler. His early painting Symphony in White #1: The White Girl (left) caused a sensation when it was exhibited after being rejected from both the Salon in Paris (the official annual exhibition) and the annual exhibition at the Royal Academy in London. The simplistic representation of a woman in a white dress, standing in front of a white curtain was too unique for Victorian audiences, who tried desperately to connect the painting to some literary source—a connection Whistler himself always denied. The artist went on to create a series of paintings, the titles of which generally have some musical connection, which were simply intended to create a sense of mood and beauty. The most infamous of these, Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875, Detroit Institute of Arts), appeared in an exhibition at London’s Grovesnor Gallery, a venue for avant garde art, in 1877 and provoked the famous accusation from the critic John Ruskin that the artist was “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”

The ensuing libel trial between Whistler and Ruskin in 1878 was really a referendum on the question of whether or not art required more substance than just beauty. Finding in favor of Whistler, the jury upheld the basic principles of the Aesthetic Movement, but ultimately caused the artist’s bankruptcy by awarding him only one farthing in damages. In The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, a collection of essays published in 1890, Whistler himself pointed out the biggest problem for the aesthetic artist was that “the vast majority of English folk cannot and will not consider a picture as a picture, apart from any story which it may be supposed to tell.”

No story or moral message

The Aesthetic Movement provided a challenge to the Victorian public when it declared that art was divorced from any moral or narrative content. In an era when art was supposed to tell a story, the idea that a simple expression of mood or something merely beautiful to look at could be considered a work of art was a radical idea. However, in its assertion that a work of art can be divorced from narrative, the ideas of the Aesthetic Movement are an important stepping-stone in the road towards Modern Art.

John Everett Millais

Sir John Everett Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Sir John Everett Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents, 1849-50, oil on canvas, 864 x 1397 mm (Tate Britain, London)

A serious departure

When it appeared at the Royal Academy annual exhibition of 1850 Christ in the House of his Parents must have seemed a serious departure from standard religious imagery. Painted by the young John Everett Millais, a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (P.R.B.), Christ in the House of his Parents focuses on the ideal of truth to nature that was to become the hallmark of the Brotherhood.

The picture centers on the young Christ whose hand has been injured, being cared for by the Virgin, his mother. Christ’s wound, a perforation in his palm, foreshadows his ultimate end on the cross. A young St. John the Baptist carefully brings a bowl of water to clean the wound, symbolic of Christ washing the feet of his disciples. Joseph, St Anne (the Virgin’s mother) and a carpenter’s assistant also react to Christ’s accident. At a time when most religious paintings of the Holy Family were calm and tranquil groupings, this active event in the young life of the Savior must have seemed extremely radical.

The same can be said for Millais’ handling of the figures and the setting in the painting. Mary’s wrinkled brow and the less than clean feet of some of the figures are certainly not idealized. According to the principles of the P.R.B., the attention to detail is incredible. Each individual wood shaving on the floor is exquisitely painted, and the rough-hewn table is more functional than beautiful. The tools of the carpenters trade are evident hanging on the wall behind, while stacks of wood line the walls. The setting is a place of work, not a sacred spot.

Painted in a carpenter’s shop

William Michael Rossetti recorded in The P.R.B. Journal that Millais started to work on the subject in November 1849 and began the actual painting at the end of December. We know from Rossetti and the reminiscences of fellow Brotherhood member William Holman Hunt that Millais worked on location in a carpenter’s shop on Oxford Street, catching cold while working there in January. Millais’ son tells us that his father purchased sheep heads from a butcher to use as models for the sheep in the upper left of the canvas. He did not show the finished canvas to his friends until April of 1850.

Scathing reviews

Although Millais’ exhibit at the Royal Academy in 1849, Isabella, had been well received, the critics blasted Christ in the House of his Parents. The most infamous review, however, was the one by Charles Dickens that appeared in his magazine Household Words in June 1850. In it he described Christ as:

a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-haired boy in a nightgown, who appears to have received a poke playing in an adjacent gutter, and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness that (supposing it were possible for any human creature to exist for a moment with that dislocated throat) she would stand out from the rest of the company as a monster in the vilest cabaret in France or in the lowest gin-shop in England.

The commentary in The Times was equally unfavorable, stating that Millais’ “attempt to associate the Holy Family with the meanest details of a carpenter’s shop, with no conceivable omission of misery, of dirt, of even disease, all finished with loathsome minuteness, is disgusting.” The painting proved to be so controversial that Queen Victoria asked that it be removed from the exhibition and brought to her so she could examine it.

At the Royal Academy

The attacks on Millais’ painting were undoubtedly unsettling for the young artist. Millais had been born in 1829 on the island of Jersey, but his parents eventually moved to London to benefit their son’s artistic education. When Millais began at the Royal Academy school in 1840 he had the distinction of being the youngest person ever to have been admitted.

At the Royal Academy, Millais became friendly with the young William Holman Hunt, who in turn introduced Millais to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and the idea for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was born. The young artists exhibited their first set of paintings in 1849, all of which were well received, but the paintings shown in 1850 were universally criticized, although none with as much fervor as Christ in the House of his Parents.

Millais’ Christ in the House of his Parents is a remarkable religious painting for its time. It presents the Holy Family in a realistic manner, emphasizing the small details that bring the tableau to life. It is a scene we can easily imagine happening, but it is still laced with the symbolism expected of a Christian subject. It is Millais’ marriage of these two ideas that makes Christ in the House of his Parents such a compelling image, and at the same time, made it so reprehensible to Millais’ contemporaries.

Sir John Everett Millais, Mariana

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Sir John Everett Millais, Mariana, 1851, oil on wood, 597 x 495 mm (Tate Britain)

The Victorian idea of a medieval woman

Rising up to stretch after a long session of embroidery, Millais’ Mariana is the epitome of the Victorian idea of a medieval woman. Set in a vaguely Gothic interior with pointed arches and stained glass windows, the painting has an air of mystery and melancholy that is typical in Victorian depictions of the Middle Ages. The 1830s-50s saw an interest in the Middle Ages which appeared to offer an alternative to the problems of industrial capitalism of the Victorian era.

Also typical of the time, is the emphasis on the isolated female figure. The dark colors and straining posture of the woman lead us to wonder about her story, and the Victorian painter always has a story to tell.

An illustration for a poem by Tennyson

Mariana is an illustration to Tennyson’s poem, lines from which were included in the catalog when the painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1851:

She only said, ‘My life is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said:

She said, “I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

The inspiration for the poem was taken from the character of Mariana in Shakespeare’s play Measure for Measure, who was locked in a moated grange (an estate with a moat around it) for years after her dowry was lost at sea in a storm, causing her to be rejected by her lover Angelo. However, the happily ever after ending found in Shakespeare’s play is not even hinted at in either Tennyson’s poem or the painting by Millais. Instead the young woman is totally enclosed and isolated by her surroundings, with even the garden visible outside the window bordered by a high brick wall. The visual imagery does not seem to suggest a happy ending for Millais’ heroine.

Pre-Raphaelite details

As is typical with the Pre-Raphaelites, Millais’ painting shows his mastery of the minute detail. The viewer can almost reach out and touch the softness of her velvet dress, and the jewels in her belt glitter against the dark blue fabric. The beautiful stained glass windows depicting an Annunciation scene were adapted from the windows in the Chapel of Merton College, Oxford. Even the smallest details such as the small mouse that runs across the floor and the light of the lamp by the prie dieu in the corner are painted with the same attention to truth to nature found in the more prominent elements of the painting.

A turning point

Mariana was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1851. Although Millais and his fellow Pre-Raphaelite artists were not well received by the critics, the attacks were not as savage as Millais had endured the previous year over his Christ in the House of his Parents. In fact, the young but influential critic John Ruskin was persuaded to send two letters to The Times praising the new style for its skill in drawing, intense color and truthfulness to nature. This was a turning point, both for the future of the Pre-Raphaelites and for Millais, whose future association with Ruskin was to be so eventful.

In Mariana, Millais has created both an essay in Pre-Raphaelite execution and an evocative literary female portrait. The viewer feels the release of her aching muscles as she leans backward, however we are also palpably aware of her isolation. It is a work that is at once vibrant and colorful, but also cold and forbidding.

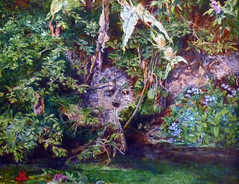

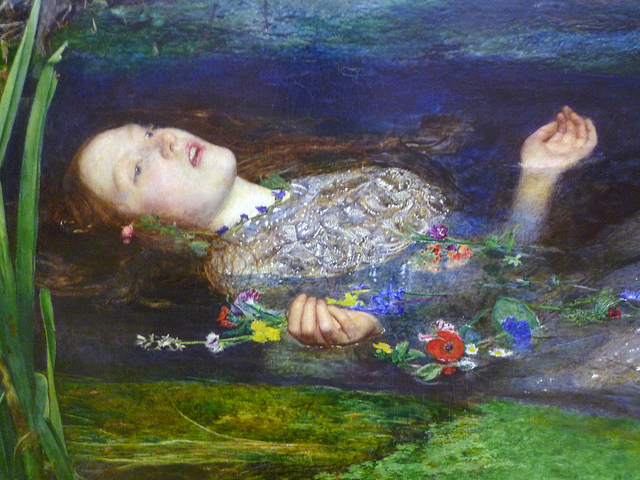

Sir John Everett Millais, Ophelia

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Sir John Everett Millais, Ophelia, 1851-52, oil on canvas, 762 x 1118 mm (Tate Britain, London)

A Pre-Raphaelite masterpiece

Ophelia is considered to be one of the great masterpieces of the Pre-Raphaelite style. Combining his interest in Shakespearean subjects with intense attention to natural detail, Millais created a powerful and memorable image. His selection of the moment in the play Hamlet when Ophelia, driven mad by Hamlet’s murder of her father, drowns herself was very unusual for the time. However, it allowed Millais to show off both his technical skill and artistic vision.

The figure of Ophelia floats in the water, her mid section slowly beginning to sink. Clothed in an antique dress that the artist purchased specially for the painting, the viewer can clearly see the weight of the fabric as it floats, but also helps to pull her down. Her hands are in the pose of submission, accepting of her fate.

She is surrounded by a variety of summer flowers and other botanicals, some of which were explicitly described in Shakespeare’s text, while others are included for their symbolic meaning. For example, the ring of violets around Ophelia’s neck is a symbol of faithfulness, but can also refer to chastity and death.

The hazards of painting outdoors

Painted outdoors near Ewell in Surrey, Millais began the background of the painting in July of 1851. He reported that he got up everyday at 6 am, began work at 8, and did not return to his lodgings until 7 in the evening. He also recounted the problems of working outdoors in letters to his friend Mrs. Combe, later published in the biography of Millais by his son J.G. Millais.

“I sit tailor-fashion under an umbrella throwing a shadow scarcely larger than a halfpenny for eleven hours, with a child’s mug within reach to satisfy my thirst from the running stream beside me. I am threatened with a notice to appear before a magistrate for trespassing in a field and destroying the hay.”

The hazards of being an artist’s model

His problems did not end when he returned to his studio in mid-October to paint the figure of Ophelia. His model was Elizabeth Siddal who the Pre-Raphaelite artists met through their friend Walter Howell Deverell, who had been impressed by her appearance and asked her to model for him.

When she met the Pre-Raphaelites Siddal was working in a hat shop, but she later became a painter and poet in her own right. She also become the wife and muse of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Millais had Siddal floating in a bath of warm water kept hot with lamps under the tub. However, one day the lamps went out without being noticed by the engrossed Millais. Siddal caught cold, and her father threatened legal action for damages until Millais agreed to pay the doctor’s bills.

Millais becomes a success

Ophelia proved to be a more successful painting for Millais than some of his earlier works, such as Christ in the House of his Parents. It had already been purchased when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1852. Critical opinion, under the influence of John Ruskin, was also beginning to swing in the direction of the PRB (the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood). The following year, Millais was elected to be an Associate of the Royal Academy, an event that Rossetti considered to be the end of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

The execution of Ophelia shows the Pre-Raphaelite style at its best. Each reed swaying in the water, every leaf and flower are the product of direct and exacting observation of nature. As we watch the drowning woman slowly sink into the murky water, we experience the tinge of melancholy so common in Victorian art. It is in his ability to combine the ideals of the Pre-Raphaelites with Victorian sensibilities that Millais excels. His depiction of Ophelia is as unforgettable as the character herself.

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Sir John Everett Millais, Portrait of John Ruskin

“Go to nature…”

Millais’s Portrait of John Ruskin depicts one of the most influential art critics of the Victorian era. Shown in front of a waterfall in Glenfinlas Scotland, Ruskin is surrounded by the wild, rocky landscape, an observer of the beauty of the natural world.

The image is in keeping with Ruskin’s own writings which recommended that artists “go to nature in all singleness of heart,” as well as his personal interests as an amateur artist and dabbler in the burgeoning science of geology.

Ruskin also completed several drawings of the area, including Study of Gneiss Rock, Glenfinlas (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) at the same spot as the background of Millais’s painting. In his own work, Ruskin shows the same meticulous attention to natural details.

A controlling mentor

The relationship between the young artist and the established critic began when Ruskin wrote two letters to The Times defending the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1851. Millais wrote to thank Ruskin, and Ruskin discovered a young artist he thought worthy of molding. In the summer of 1853, Millais was invited to visit Scotland with Ruskin and his wife Effie, who had previously posed for Millais’s painting The Order of Release 1746 (1852-3). Work began on the portrait almost immediately. Millais found the experience difficult, as Ruskin was an extremely controlling mentor, directing much of the production of the painting. Millais reported that he completed most of the background in Scotland, during July and August, although work on the picture was slow. In January of 1854 Ruskin sat for Millais in his studio and by April the face was completed. The painting was not finished until December 1854 when Ruskin’s father paid for the picture.

The end of a marriage

The painting was not the only thing to come out of the vacation, however. Effie was extremely unhappy in her marriage to the staid and conservative Ruskin, and she and Millais fell in love. She was ultimately to leave Ruskin and have their marriage annulled on the grounds of non-consummation. Effie married Millais in 1855 and the two eventually had eight children. Unfortunately, her reputation was considered tarnished because of the rigid Victorian social code and many people, including Queen Victoria, refused to receive her. Millais, who was created a baronet in 1885 and eventually elected as the President of the Royal Academy shortly before his death in August 1896, became more and more a part of the artistic establishment, and Effie’s exclusion from society was a source of unhappiness. It was only towards the end of Millais’s life, largely through the intervention of Princess Louise, that Effie was received in polite society.

Millais’s Portrait of Ruskin is an intimate glimpse at one of the most important figures in the Victorian art world. The painstaking attention to the details of the rocks and fast moving water shows the Pre-Raphaelite style at its finest, while the upright, serious figure of Ruskin hints at the sitter’s personality. The portrait is a rare meeting of art, science, and personal drama.

Additional resources:

Press release from the Ashmolean Museum on the acquisition of this painting

Alastair Grieve, “Ruskin and Millais at Glenfinlas,” Burlington Magazine, vol. 138 (1996), pp. 228-234. (JSTOR)

A Portrait of John Ruskin and Masculine Ideals of Dress in the Nineteenth Century

While the skill of a portrait artist is often judged by whether or not the work resembles the sitter, a portrait may also reveal something about the sitter as well as fashionable norms of the time. What does John Ruskin reveal about himself in his choice of attire for his commissioned portrait by John Everett Millais? In this life-size oil painting, Millais depicts the art critic and polymath standing on a narrow rocky ledge looking downstream as the river rushes behind him. He is dressed in formal daywear suitable for a gentleman — a dark-colored wool double-breasted frock coat that comes to his knees worn over a crisp white shirt, and gray trousers.

Masculine dress in the nineteenth century

During the nineteenth century, the dress of men differed markedly from that of the previous century. They cast aside the flamboyant, colorful and decorative looks worn by men like Charles II in the eighteenth century. Instead, the elegant gentleman of the Victorian era was often seen wearing relatively dark and sober attire. In dressing this way, men seemed to have rejected fashion, a phenomenon historians often refer to as “The Great Male Renunciation of Fashion.” The contrast between the seemingly dark and sober menswear and the ornate and decorative dress worn by women aligned with traditional gender roles that cast women as ornamental accessories of their fathers or husbands in the nineteenth century.

Nonetheless, a closer look at menswear of the nineteenth century shows that fashion was indeed present and can be found in small and subtle details, such as the quality of the cloth, the length of the coat, the style of the necktie, the height of the collar, and the fit of the trousers. In fact, it was just these types of details that conveyed a man’s status, wealth and identity.

Reading the clues of dress

Ruskin is wearing an ensemble that was considered formal urban daywear. This type of dark and sober costume was the uniform of respectability, worn by members of Parliament, bankers, judges, doctors and gentleman. He wears this elegant attire even though he is deep in the wilderness in a hard-to-reach ravine in Scotland, communicating the idea that he is an educated gentleman.

Ruskin’s crisp white collared shirt emerges at the neckline and cuffs to show that he has the financial means to have his clothing laundered. The black or dark blue stock or necktie, wrapped smoothly around his neck, also denotes his social class. The dark long-waisted wool frock coat that comes to his knees creates a smooth line over his slender body and exemplifies the work of a skilled tailor.

It is interesting that Ruskin did not select a looser-fitting hunting jacket for his portrait but instead chose clothing that he might have worn to give a lecture on architecture and painting. Millais’ initial sketches for this portrait made on site in Glen Finglas (Scotland) show Ruskin wearing this or a similar formal daywear ensemble even though the painting was later finished in the artist’s studio in London.

A comparable ensemble dated to 1852 from the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art reveals the waistcoat or vest typically worn under the frock coat. The key difference is that this ensemble is accessorized with two items found in every gentleman’s wardrobe from that time — a silk top hat and a walking stick.

Ruskin’s walking stick

Ruskin chose more casual versions of these accessories for his portrait by Millais. In the painting, he holds a brown felt hat in his left hand and a walking stick fashioned from a tree branch in the other. He is a gentleman, but with these choices he reveals his affinity for and love of nature, a topic that he also lectured on. He once wrote: “I would rather teach drawing that my pupils learn to love nature, than teach the looking at nature that they may love to draw.”

In subsequent decades, Ruskin would be described as a slightly stooped figure who was somewhat old-fashioned in his dress. In 1884, the young Beatrix Potter recorded seeing Ruskin at the Royal Academy in her diary noting that he was “one of the most ridiculous figures” she had ever seen, and she observed that he wore “a very old hat, much necktie and aged coat buttoned up to his neck.” Nonetheless, in 1853-1854 when Millais painted his portrait, Ruskin emulated the ideal attire worn by an elegant gentleman, albeit with his own unique touch.

Details of men’s attire are often less visible than women’s dress, especially since men’s suits are one of the most ubiquitous and enduring symbols of masculinity. Nonetheless, small details, such as the choice of accessories or the cut and quality of a suit, may reveal important clues to a sitter’s identity.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Read more about this portrait of John Ruskin

Christopher Breward, The Suit: Form, Function & Style (London: Reaktion Books, 2016)

James S. Dearden, John Ruskin: A Life in Pictures (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1999)

Ingrid E. Mida, Reading Fashion in Art (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020)

Sir John Everett Millais, The Vale of Rest

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Sir John Everett Millais, The Vale of Rest: where the weary find repose, 1858 (partially repainted 1862)

Inspired by the sunset

An October sunset was the inspiration for the evocative The Vale of Rest by John Everett Millais. In the foreground, two nuns in the graveyard, one digging and one looking out at the viewer, serve as a counterpoint to the colorful display of nature in the background. The scene is peaceful, tranquil, and without the explicit narrative often found in Victorian paintings (think about Hunt’s Awakening Conscience for example), but it is nonetheless rich in symbolism. The artist himself stated that this was his favorite painting.

Mortality & the cycles of nature

Millais apparently thought of the painting as a companion to his painting Spring (1856-9), also first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1859. Both together and separately, the two pictures relate to the traditional theme of mortality and the cycles of nature. The autumn setting of The Vale of Rest emphasizes the annual reminder of death in the falling foliage and shortened hours of daylight. This feeling is emphasized by the two nuns, one vigorously digging a grave and the other who prominently wears a rosary attached to a skull. The quiet of the scene is marred only by the sound of the shovel as it hits the dirt.

Painted out-of-doors

Although we often associate artists painting outdoors to capture the effects of light with Monet, Renoir and the Impressionist group, the Pre-Raphaelites also painted outdoors. The background of this painting is the garden of Millais’ in-laws home in Perth, Scotland, except, of course, for the gravestones, which were painted in Kinnoull churchyard, Perth. According to a long description of the production of the painting by his wife, Effie and recorded by their son J.G. Millais, “the sunsets were lovely for two or three nights . . . the effect lasted so short a time that he had to paint like lightning.” In a letter to William Holman Hunt, Millais tells his friend that he was painting the picture, figures and all, outdoors, despite the fact that it was extremely cold.

Growing success

In many of the paintings completed after The Vale of Rest, Millais began to move towards more saleable pictures. Although he had moved to Scotland after his marriage in July 1855, Millais and family returned to London in 1861, and many have argued that the change in his work reflects the need to support his growing family. He was to be increasingly successful, being elected RA (Royal Academician) in 1863 and ultimately serving as the President of the Royal Academy, although briefly, from early 1896 until his death in August of that year. In 1885 Millais also had the distinction of being the first artist to be created a baronet.

The Vale of Rest is a transitional work in Victorian art. The attention to detail and truth to nature are firmly rooted in Pre-Raphaelitism, while the lack of a clear subject relates to the new ideas of the Aesthetic Movement and the concept of art for arts sake, which was to become so prominent in the 1860s and 70s. The quiet and contemplative mood of the painting encourages the viewer to enjoy the beauty of nature, while, perhaps, also pondering our own mortality.

Additional resources:

Spring (Apple Blossoms) at the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Liverpool

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

William Holman Hunt

William Holman Hunt, Claudio and Isabella

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): William Holman Hunt, Claudio and Isabella, 1850, oil on mahogany, 758 x 426 x 10 mm (Tate Britain)

From William Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, Act III, scene 1 (a room in a prison):

ISABELLA What says my brother?

CLAUDIO Death is a fearful thing.

ISABELLA And shamed life a hateful.

CLAUDIO Ay, but to die, and go we know not where;

To lie in cold obstruction and to rot;

This sensible warm motion to become

A kneaded clod; and the delighted spirit

To bathe in fiery floods, or to reside

In thrilling region of thick-ribbed ice;

To be imprison’d in the viewless winds,

And blown with restless violence round about

The pendent world; or to be worse than worst

Of those that lawless and incertain thought

Imagine howling: ’tis too horrible!

The weariest and most loathed worldly life

That age, ache, penury and imprisonment

Can lay on nature is a paradise

To what we fear of death.

ISABELLA Alas, alas!

A moral dilemma

William Holman Hunt’s Claudio and Isabella illustrates not only the Pre-Raphaelite fascination with William Shakespeare, but also the artist’s particular attraction to subjects dealing with issues of morality. Taken from the play Measure for Measure, which tells the story of Claudio, who has been sentenced to death by Lord Angelo (the temporary ruler of Vienna) for impregnating his fiancée.

Claudio’s sister Isabella, a nun, goes to Angelo to plead for clemency for her brother and is shocked that he suggests that she trade sex for her brother’s life. Of course, she refuses, and Claudio initially agrees with her decision, but later changes his mind. Hunt depicts the moment when the imprisoned Claudio suggests that Isabella sacrifice her virginity to gain his freedom.

It was the type of subject that appealed to Hunt, who liked themes to do with questions of guilt and sinful behavior, such as his well known painting The Awakening Conscience (1853).

Claudio and Isabella

Claudio’s face, which is partly in shadow, looks down and away from his sister. His slouching posture, the rich texture of his dark, yet colorful clothes and pointed medieval-looking shoes are a sharp contrast to the stark white of the nun’s habit, her upright posture and unwavering gaze. Sunlight from the prison window lights Isabella’s face and permits a glimpse of apple blossoms and a church in the distance.

The interior of the scene was painted at Lollard Prison at Lambeth Palace, and the crumbling masonry around the windows and the rusty metal of the shackle that bind Claudio’s leg detail the less than desirable conditions.

Hunt also painted the lute hanging in the window while at the prison. The lute with its red string is symbolic of lust, but the fact that it is placed in the sunshine rather than the gloom of the cell lessens the negative impact. The petals of apple blossom scattered on Claudio’s cloak on the floor, although not added until 1879, are intended to show that Claudio is willing to compromise his sister to save himself.

Financial difficulties

Claudio and Isabella was begun in 1850 after Hunt received a small advance from the painter Augustus Egg. Poor reviews of the Pre-Raphaelite paintings at the Royal Academy of 1850 had created financial difficulties for Hunt. He continued to work on the painting for the next several years, finally exhibiting the picture at the Royal Academy of 1853.

“Death is a fearful thing”

The painting appeared with a quotation from the play carved into the frame, a devise Hunt was to explore in many of his paintings, as a way of reinforcing his message. The short notation “Claudio: Death is a fearful thing. Isabella: And shamed life a hateful,” serves not only to point to the exact moment in the play, but also as a reminder of the underlying moral dilemma of the subject. The ability to bring to life these moments of ambiguity was one of Hunt’s greatest achievements.

Additional resources

Professor Rusche on this painting

Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource from Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

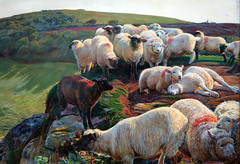

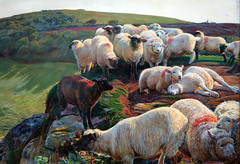

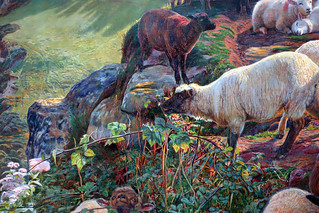

William Holman Hunt, Our English Coasts (Strayed Sheep)

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): William Holman Hunt, Our English Coasts (“Strayed Sheep”), 1852, oil on canvas, 432 x 584 mm (Tate Britain, London)

A daring composition

William Holman Hunt’s Our English Coasts (Strayed Sheep) is a remarkably original work of art for 1852. Painted largely out of doors at the “Lover’s Seat” (a scenic outlook) above Covehurst Bay near Hastings on the south coast of England, the scene captures a tranquil spot inhabited only by a flock of sheep. The rather daring composition and the attention to natural detail make this painting unique.

Hunt captures the beauty of an English summer day. The brightness of the sunlight is interrupted only by the shadows of the clouds they move across the landscape. The sea glitters in the distance on the far left. The cliffs are pushed up to the top of the picture frame, leaving little room for the sky. Most daring, however, is the massing of the sheep on the edge of the cliff on the right side of the painting, creating an asymmetry to the composition.

Although there are no people in the landscape, the sheep take on very human characteristics, for example the two sheep at the very edge of the canvas, one of whom lovingly rests his head on the back of the his companion. In the corner just underneath, a black sheep stares malevolently out at the viewer.

Pre-Raphaelite truth to nature

True to the ideals of Pre-Raphaelitism, Hunt painted every flower, bramble and blade of grass with extreme attention to detail. The texture gives the impression that you could reach out feel the uneven clumps of wool on the sheep, and Hunt even pays attention to the red marking, used to differentiate ownership, on each member of the flock. Hunt, who had introduced the Pre-Raphaelites to the ideas of John Ruskin, was perhaps the most faithful follower of Ruskin’s advice to “go to Nature in all singleness of heart.”

Political and Moral Content

Also following in the tradition of Ruskin is the fact that the painting carries a moral content. The title Our English Coasts related to the fact that at the time of the unguarded state of the many miles of English coastline was a serious topic of discussion at the time. The European revolutions of 1848 had made Britons nervous, and it was as yet unclear what the relationship was to be with France’s new ruler Napoleon III.

The selection of a location near Hastings, the landing site of the Norman Invasion of 1066, possibly relates to the last successful invasion of the island in British history. The painting’s subtitle, Strayed Sheep, relates to the more Biblical message of the painting. There is no shepherd tending the flock, some of which are perched perilously close to the edge of the cliff. In this the message relates to the moral of Hunt’s The Hireling Shepherd, in which a beautiful woman distracts the shepherd while the flock behind him gets into all kinds of trouble. Interestingly, when Hunt exhibited the painting in France in 1855, the Our English Coasts part of the title was dropped.

Hunt and the Pre-Raphaelites

Hunt was born in London in 1827 and became a student at the Royal Academy School in 1844, where he met Millais. He also became a close friend of Dante Gabriel Rossetti when the two bonded over a mutual regard for the work of the poet Keats. He was an important force in the early years of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and the subjects and moral content of his paintings frequently reflect his own deeply religious nature.

The English countryside

The realism of Our English Coasts (Strayed Sheep) transports the viewer to the spot. One can feel the breeze off the English Channel, and the heat of the summer sun. The picturesque blend of sheep and landscape typically found in the English countryside are here seamlessly intertwined with the moral message. Hunt has in no way created a replica of an earlier painting (which was the original commission), but a wholly original work of art.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Google Art Project

William Holman Hunt at the Google Art Project

Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource from the Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience, 1853, oil on canvas, 762 x 559 mm (Tate Britain, London)

A Fallen Woman (with a New Twist)

William Holman Hunt’s painting, The Awakening Conscience, addresses the common Victorian narrative of the fallen woman (for more about this subject, see Stanhope’s Thoughts of the Past). Trapped in a newly decorated interior, Hunt’s heroine at first appears to be a stereotype of the age, a young unmarried woman engaged in an illicit liaison with her lover. This is made clear by the fact that she is partially undressed in the presence of a clothed man and wears no wedding ring.

However, Hunt offers a new twist on this story. The young woman springs up from her lover’s lap. She is reminded of her country roots by the music the man plays (the sheet music to Thomas Moore’s Oft in the Stilly Night sits on the piano), causing her to have an awakening prick of conscience.

The symbolism of the picture makes her situation as a kept woman clear—the enclosed interior, the cat playing with a bird under the chair, and the man’s one discarded glove on the floor all speak to the precarious position the woman has found herself in. However, as she stands up, a ray of light illuminates her from behind, almost like a halo, offering the viewer hope that she may yet find the strength to redeem herself.

The theme of the fallen woman was popular in Victorian art, echoing the prevalence of prostitution in Victorian society. Hunt’s redemptive message is unusual when compared to other examples of this theme. For example, Richard Redgrave’s The Outcast (1851), which shows a young unwed mother and her baby being cast out into the snow by her disgraced father, while the rest of her family pleads for mercy. Countless other paintings of the period emphasize the perils of stepping outside the bounds of acceptable morality with the typical conclusion to the story being that the woman is ostracized, and inevitably, suffers a premature death. By contrast, Hunt offers the viewer the hope that the young woman in his painting is truly repentant and can ultimately reclaim her life.

Pre-Raphaelite in style

The Awakening Conscience is one of the few Pre-Raphaelite paintings to deal with a subject from contemporary life, but it still retains the truth to nature and attention to detail common to the style. The texture of the carpet, the reflection in the mirror behind the girl and the carvings of the furniture all speak to to Hunt’s unwavering belief that the artist should recreate the scene as closely as possible, and paint from direct observation. To do that, he hired a room in the neighborhood of St. John’s Wood. The picture was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1854, and unfortunately for Hunt, met with a mixed reception. While Ruskin praised the attention to detail, many critics disliked the subject of the painting and ignored the more positive spiritual message.

A deeply religious man

For Hunt, the moral of the story was an important element in any of his subjects. He was a deeply religious man and committed to the principles of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and John Ruskin. In fact, shortly after this painting was completed, Hunt embarked on a journey to the Holy Land, convinced that in order to paint religious subjects, he had to go to the actual source for inspiration. The fact that a trip to the Holy Land was a difficult, expensive and dangerous journey at the time was immaterial to him.

The Awakening Conscience is an unconventional approach to a common subject. Hunt’s work reflects the ideal of Christian charity espoused in theory by many Victorians, but not exactly put into practice when dealing with the issue of the fallen woman. While others emphasized the consequences of one’s actions as a way of discouraging inappropriate behavior, Hunt maintained that the truly repentant can change their lives.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Google Art Project

William Holman Hunt in the Google Art Project

The Pre-Raphaelites at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource at Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

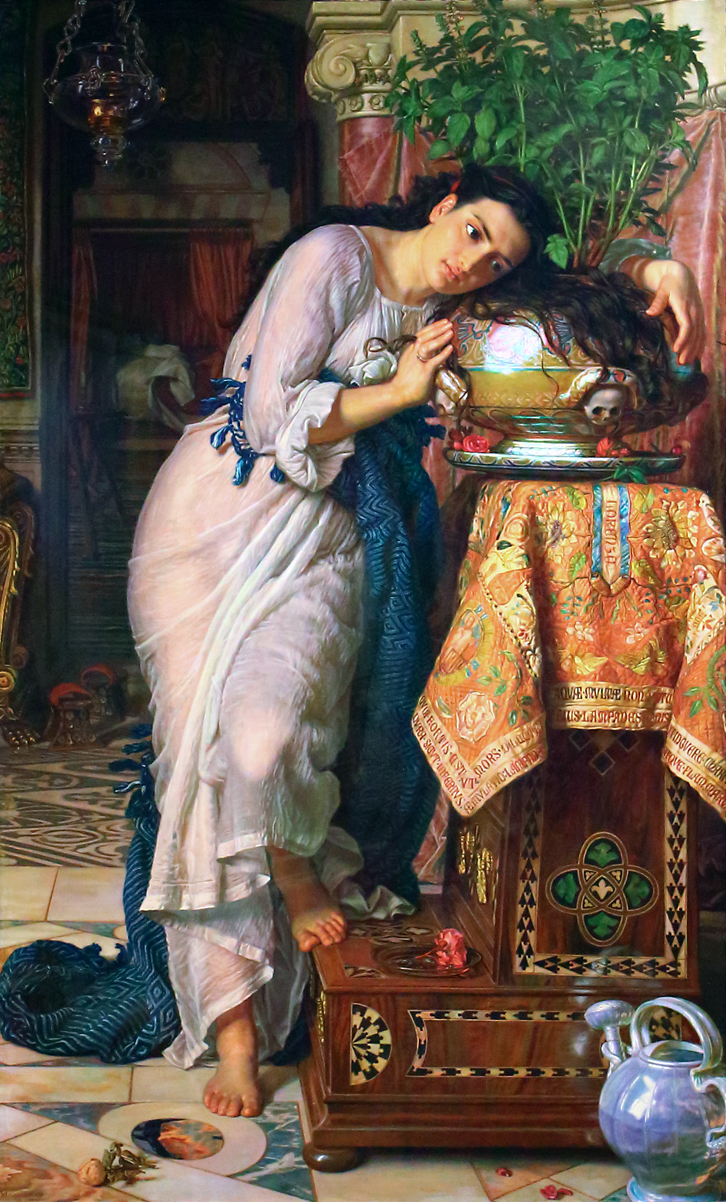

William Holman Hunt, Isabella or the Pot of Basil

One of the things that initially drew the Pre-Raphaelites together was a shared admiration for the writings of John Keats. Throughout their careers, subjects from Keats’ poems frequently supplied the narratives for the paintings done by the members of the PRB (Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood), but William Holman Hunt’s Isabella or the Pot of Basil (1866-8) is an innovative interpretation of the subject.

Keats’ Isabella or the Pot of Basil (published in 1820) is based on a story from the Renaissance author Boccaccio’s Decameron. It explores the traditional theme of star-crossed lovers. The poem tells the tragic tale of Isabella and Lorenzo, who is employed by Isabella’s brothers. Unhappy with the blossoming love between the pair, the brothers send Lorenzo on a trip and have him killed, but Lorenzo appears to Isabella as a ghost and tells her where to find his body. Isabella digs up the body, cuts off Lorenzo’s head and buries it in a pot of basil, which she waters with her tears. Eventually her brothers become suspicious, steal the pot, and flee. Isabella goes mad with grief and dies. Like the narratives of so many Victorian paintings, the course of true love does not run smoothly.

The subject had been treated by John Everett Millais in 1848-9 in one of his first forays into Pre-Raphaelite painting. Millais’ painting shows the lovers, oblivious to the others around them as Lorenzo shyly offers Isabella a blood orange on a plate. Isabella looks demurely downward while one of her brothers kicks a dog in fury over their obvious regard for each other. Millais’ Isabella is a stunning example of the mastery of the medieval detail for which the Pre-Raphaelites are known, and the pale, thin face of Isabella is reminiscent of a Renaissance Madonna.

In contrast, Hunt’s image of an exotic, dark-haired Mediterranean-looking woman is at odds both with the earlier painting and the description in Keats’ poem. Here Isabella stares into space, her arms tenderly embracing a pot decorated with skulls, which Hunt based on examples he had seen in Florence. She is clad in a gauzy, clinging nightdress emphasizing her curves, and her feet are bare, creating a far more sensual version of the subject. Hunt’s Isabella also appears to be a more robust woman than the typical pale, fragile looking women often found in Victorian art. Ever practical, Hunt said that he wanted her to look as if she was actually capable of cutting off a head.

Although the attention to detail found in Hunt’s earlier Pre-Raphaelite paintings remains, his inclusion of vaguely foreign elements such as the inlay of the furniture, the elaborate tapestry on which the pot sits and the richly designed tile floor come more from the interest in the exotic found in paintings of the Aesthetic Movement. His approach to Isabella and the Pot of Basil has as much in common with later Victorian artists such as Frederic Lord Leighton and his paintings of classically dressed single female figures, as it does with his Pre-Raphaelite roots.

The painting was begun in Florence, where Hunt and his new wife, Fanny Waugh, were stopped while traveling in 1866. In October Fanny gave birth to a son but contracted a fever and died in December. Hunt used Fanny’s likeness as the model for his Isabella and her mournful gaze may be an expression of his own grief. After working on the painting for some time, Hunt finally exhibited the work in 1868 at the showroom of the art dealer Ernest Gambart, where it was generally well received by critics.

Throughout his career, Hunt stayed closest to the aesthetic of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in his attention to detail and his insistence on narrative content. His use of the Keats poem and his masterful treatment of small things, such as the minutia of the stitching on the beautiful tapestry, point to his continuing adherence to the ideals of the PRB, while his re-interpretation of the heroine shows his continued growth as an artist.

Additional resources:

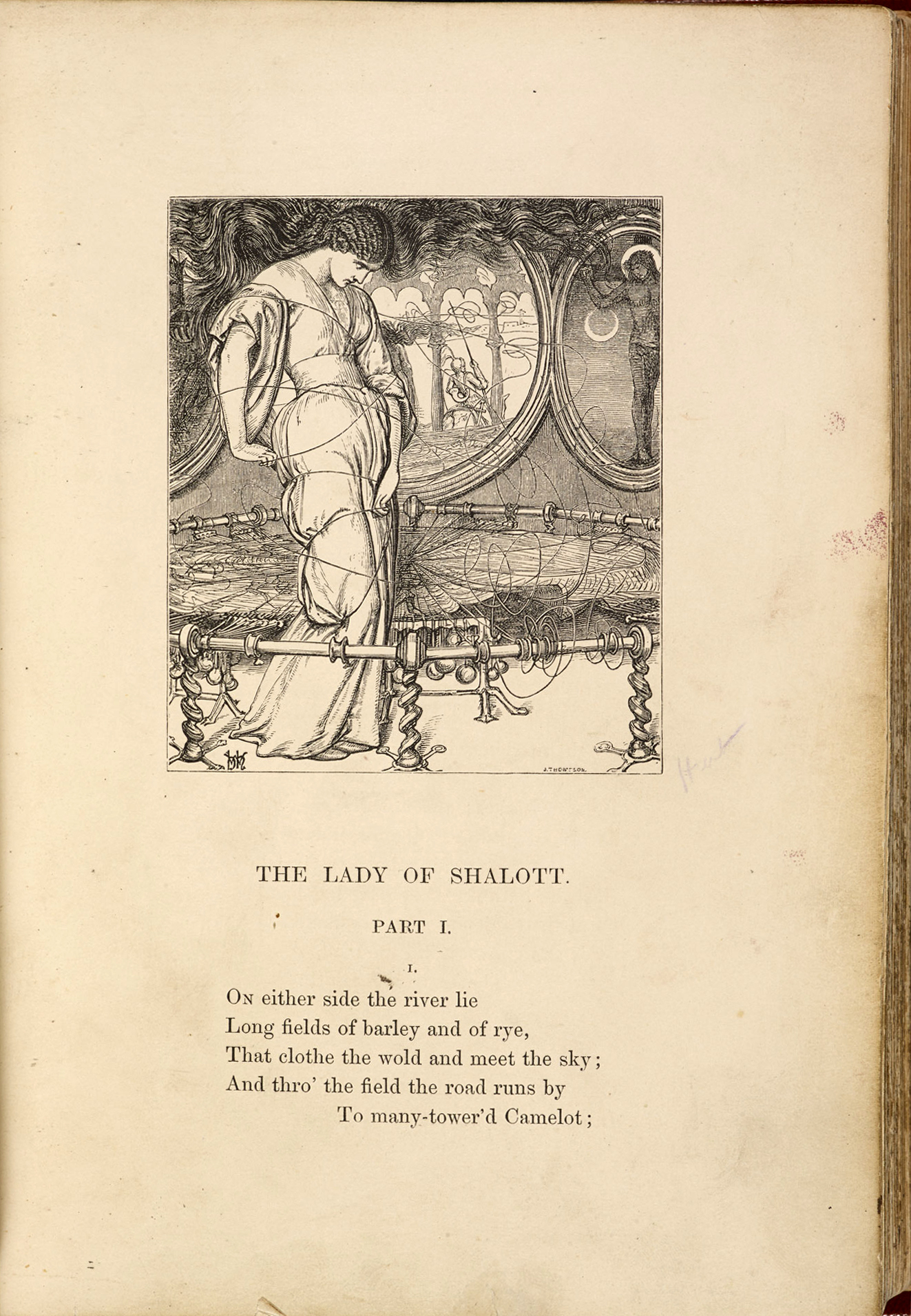

William Holman Hunt, The Lady of Shalott

A Lady Cursed

In the 1880s, William Holman Hunt turned to the poetry of Sir Alfred, Lord Tennyson, a favorite Victorian literary source, in his painting The Lady of Shalott. Hunt’s painting is a virtuoso performance, using the meticulous detail of Pre-Raphaelitism to capture the most dramatic moment in the story. The painting was based on a drawing for a lavish edition of Tennyson published in 1857 known as the Moxon Tennyson (after the publisher).

The Victorians loved nothing better than a beautiful, tragic heroine, preferably one in medieval clothing, which explains their enduring fascination with Tennyson’s The Lady of Shalott. One of his many poems based on the legends of King Arthur, Tennyson tells the story of a lovely lady confined to “Four gray walls, and four gray towers,” and cursed to constantly weave scenes that she can only observe through a mirror. As the poem explains:

No time hath she to sport and play:

A charmed web she weaves alway.

A curse is on her, if she stay

Her weaving either night or day,

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be;

Therefore she weaveth steadily,

Therefore no other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

Unfortunately for the lady, her routine of constantly weaving reflections is quite literally shattered when she observes Sir Lancelot riding by and actually looks out the window rather than at the shadowy images in the mirror.

She left the web, she left the loom

She made three paces thro’ the room

She saw the water-flower bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She look’d down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack’d from side to side;

‘The curse is come upon me,’ cried

The Lady of Shalott.

Knowing that the end is near, the final part of the poem recounts how the lady writes a message for those that will find her body, gets into a boat, and floats down the river to Camelot. In this, Tennyson’s poem ends as did many, many other stories popularized during the era, with the untimely demise of the lovely heroine.

The subject was frequently illustrated, the most familiar example being John William Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott, which depicts a beautiful but stricken looking lady dying as she slowly floats down the river. In selecting this of the part of the story, Waterhouse was not alone, as the vast majority of renditions of this subject focused on the trip down river, with the lady either already dead or about to die.

In contrast, Hunt illustrated the most active part of the poem, when the lady actually looks out the window, causing the mirror to crack. According to the text, “she made three paces thro’ the room,” and in Hunt’s figure, the swinging arms and the wild, wind-blown look of her flowing hair create the sensation of a slow rhythmic dance. The lady struggles to remove threads of her tapestry, which “out flew the web and floated wide,” creating long colored strings that bind the figure. Much of this can also be seen in the original drawing and were elements not appreciated by Tennyson himself who complained that her hair was like a “tornado” and that the threads encircling her body were an addition to the actual text of the poem.

Symbols and Meanings

In the painting, Hunt added many symbolic references. The cracked mirror behind the lady’s head shows Lancelot on his way to Camelot and the river that will take her on her final journey. The subject of the tapestry she weaves, Sir Galahad delivering the Holy Grail to King Arthur, provides a virtuous counterpoint to Lancelot, whose adultery with Queen Guinevere ultimately brings down Camelot. To one side of the mirror, a decorative panel depicting Hercules trying to pluck a golden fruit in the Garden of Hesperides is reminiscent of Renaissance relief sculpture, something Hunt saw much of during an earlier stay in Florence. The same can be said for the decorative tile floor, which is similar to that used by Hunt in his earlier painting Isabella or the Pot of Basil begun during his stay in Florence.

Hunt was a religious man, and included elements that may be interpreted as Christian symbolism—a pair of empty shoes and two purple irises. In the Bible shoes are often removed before walking on sacred ground. For example, a similar device is used in the famous Northern Renaissance painting by Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, which was a favorite of the Pre-Raphaelites. The delicately painted irises are associated with faith, hope, and wisdom, and for a Victorian audience intimately aware of the language of flowers, this inclusion may have had special meaning for the tragic lady who was “half sick of shadows,” and in the throes of making a life-changing decision.

Feminist scholars have noted that the story can be seen as a cautionary tale of what happens to women who flout the rules; in this case it is the lady’s obvious sexual desire for Lancelot that drives her decision to actually look out the window and bring the curse upon herself. And although a moralistic meaning would certainly have appealed to Hunt, his depiction of the lady is not unsympathetic. The reflection of the bright sunshine in the mirror is in sharp contrast to the darkness around the lady’s face and upper torso, while her lower half is bathed in light. His lack of overt condemnation of her actions is reminiscent of his more charitable approach towards what Victorians saw as the sin of prostitution in his earlier painting The Awakening Conscience. Although as a reader one must wonder how she ended up cursed in a tower in the first place, we are forced to admire her decision to free herself from her prison.

The Lady of Shalott is a powerful example of later Pre-Raphaelitism. At a time when many artists were moving towards the ideas of Aestheticism where beauty is more important than subject, Hunt’s picture exhibits his meticulous attention to detail combined with his desire to include a narrative. His focus on the climatic action of the story, rather than the passivity of the lady’s death, grips his viewer with the moment of decision that will change the course of her life. Although Victorian painting abounds with images of women who, by the end of the story, will end up dead, Hunt’s portrayal of his subject shows a woman unwilling to accept the drudgery of her life and ready to make a change, no matter what the cost.

Additional resources

Ford Madox Brown

Ford Madox Brown, The Last of England