8.2: INDIVIDUAL VS CULTURAL GROUPS

- Page ID

- 10158

Often when one thinks of an artist, the image is of someone doing solitary work in a studio. During the Romantic period of the late eighteenth century until around 1850, artists, writers, and composers were associated with individualism and with working alone; this trend continued to develop up until recent times. The Romantic period valued and celebrated individual originality with musical and literary geniuses such Ludwig van Beethoven, Frédéric Chopin, Robert Schumann, John Keats, Edgar Allen Poe, and Mary Shelley. The visual arts boasted such geniuses asFrancisco Goya, Eugène Delacroix, William Blake (1757-1827, England), and Antoine-Jean Gros (1771- 1835, France). (Figures 8.6 and 8.7) Artists of the period exemplified the Romanticvalues of the expression of the artists’ feelings, personal imagination, and creative experimentation as opposed to accepting tradition or popular mass opinion. Artists in the period broke traditional rules; indeed, they considered it desirable to break the rules and overthrow tradition.

Often when one thinks of an artist, the image is of someone doing solitary work in a studio. During the Romantic period of the late eighteenth century until around 1850, artists, writers, and composers were associated with individualism and with working alone; this trend continued to develop up until recent times. The Romantic period valued and celebrated individual originality with musical and literary geniuses such Ludwig van Beethoven, Frédéric Chopin, Robert Schumann, John Keats, Edgar Allen Poe, and Mary Shelley. The visual arts boasted such geniuses asFrancisco Goya, Eugène Delacroix, William Blake (1757-1827, England), and Antoine-Jean Gros (1771- 1835, France). (Figures 8.6 and 8.7) Artists of the period exemplified the Romanticvalues of the expression of the artists’ feelings, personal imagination, and creative experimentation as opposed to accepting tradition or popular mass opinion. Artists in the period broke traditional rules; indeed, they considered it desirable to break the rules and overthrow tradition.

From the Medieval to the Baroque periods, however, artists worked together in workshops and guilds, and schools were formed that stressed the importance of

From the Medieval to the Baroque periods, however, artists worked together in workshops and guilds, and schools were formed that stressed the importance of

preserving heritage and history through rigorous and systematic artistic training.

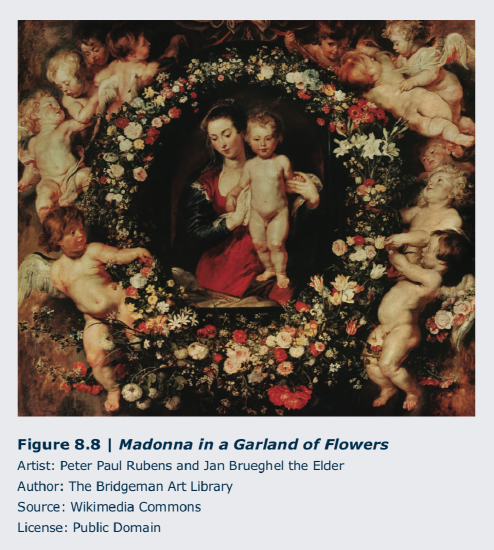

Large-scale commissions often required numerous hands to complete a work, emphasizing collaboration. Nevertheless, the artwork was expected to have a consistent style and quality of craftsmanship. To satisfy those various needs, artists often specialized in a particular type of subject matter. For example, Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640, Germany, lived Flanders) and Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625, Flanders) collaborated on more than twenty paintings over twen-ty-five years. (Figure 8.8) In their Madonna in a Garland of Roses, Rubens’s celebrated skill as a figurative painter can

be seen in the serenely glowing face of the Virgin Mary and energetic cavorting of the cherubs surrounding the circular arrangement of flowers painted with accuracy and delicacy by Brueghel, who was known for his lively nature scenes.

A recent study by a Yale University researcher found the perception of high quality art today is that it is produced by a single individual. If produced by two or three people, as in a mural or public work projects, the value of the art drops. For creative works, perceptions of quality therefore appear to be based on perceptions of individual, rather than total effort. Nevertheless, a new trend across the world in general suggests that this tradition, which first arose in the Westduring the Renaissance, is not the norm around the globe; that is, the value of art as located in the single artist who produces art individually and alone may be more specifically based in certain cultures. Artists in the twenty-first century are collaborating with others through social media and/or face-to-face encounters. It is interesting to remember that the word “art” derives from a root that means to “join” or fit together. A whole constellation of ideas and practices can be accomplished through networking and collaboration as artists participate in group residencies and apprenticeships similar to workshop traditions of centuries ago to learn the customary methods and advanced techniques of their art.

A recent study by a Yale University researcher found the perception of high quality art today is that it is produced by a single individual. If produced by two or three people, as in a mural or public work projects, the value of the art drops. For creative works, perceptions of quality therefore appear to be based on perceptions of individual, rather than total effort. Nevertheless, a new trend across the world in general suggests that this tradition, which first arose in the Westduring the Renaissance, is not the norm around the globe; that is, the value of art as located in the single artist who produces art individually and alone may be more specifically based in certain cultures. Artists in the twenty-first century are collaborating with others through social media and/or face-to-face encounters. It is interesting to remember that the word “art” derives from a root that means to “join” or fit together. A whole constellation of ideas and practices can be accomplished through networking and collaboration as artists participate in group residencies and apprenticeships similar to workshop traditions of centuries ago to learn the customary methods and advanced techniques of their art.

8.2.1 Nation

The Kingdom of Benin, located in the southern region of modern Nigeria and home to the Edo people, was ruled by a succession of obas, or divine kings. It grew from a city-state into an empire during the reign of Oba Ewuare the Great (r. 1440-1473). From 1440, obas ruled the kingdom until it was taken over by the British in 1897. Remarkably, the obas and people of Benin remained in control of their trading relations with Europeans and without interference from the rulers of the nations they traded with until the second half of the nineteenth century, prior to foreign rule. The city of Benin prospered and grew through trade with the Portuguese, Dutch, and British.

One of the benefits of dealing with merchants sailors who traveled the seas was the variety of goods they brought with them and were eager to trade for foodstuff grown or refined by the Edo people. In particular, the Edo treasured brass and coral, along with the ivory they acquired through elephant hunts. Those materials were reserved for the oba and his court, and were used in abundance in the wide array of ceremonial and sacred objects created under each ruler. Kingship was passed from father to firstborn son, and, upon ascending to the throne, the new oba was expected to create an altar made of brass for his father, as well as one for his mother, generally in ivory, if she had attained the status of queen mother. The new oba also created a brass head to honor his predecessor. (Figure 8.9) Over time, objects such as plaques, bells, masks, chests, and additional altars made of brass or ivory, some adorned with coral, were added. Some were used to commemorate momentous events and honor heroes, but the majority of royal objects were used in ceremonial and symbolic support of the oba, his ancestors and subjects, and the kingship itself.

This nineteenth-century brass head of an oba, for example, is not meant to be a portrait of an individual king so much as a representation of the divine nature and power of being king. The oba derives his power from his interactions with and control over supernatural forces. He is allied with and assisted by his deified ancestors, whom he honors through rituals, offerings, and sacrifices. In stressing this continuity of kingship and his rightful place in that unbroken chain, the oba strengthens his own power and that of his people and nation.

The welfare of the kingdom rests on the oba’s head, a heavy burden, which is emphasized in representations of him using a proliferation of objects weighing upon him (Oba Erediauwa: olivernwokedi.files.wordpres...45743558468606 60_n.jpg). But, he does not bear the weight of ruling alone; he works with and relies on his advisors and subjects as they support him. That support is shown literally when the oba is in full ceremonial regalia. In this photograph of the current oba, Erediauwa, the King is shown in his royal garb, heavily beaded in coral with ivory bracelets and plaques at his waist; an attendant, supporting his right arm, is helping Oba Erediauwa bear the weight of kingship on behalf of the nation of Edo people.

Following George Washington’s celebratory visit to Charles- ton, South Carolina, in May 1791, the Charleston City Council voted to celebrate the national hero by having John Trumbull (1756-1843, USA) paint a life-size portrait of the President and hero of the Revolutionary War (1775-1783) to “hand down to posterity the remembrance of the man to whom they are so much indebted for the blessings of peace, liberty and indepen- dence.”2 Having been Washington’s aide-de-camp during the War of Independence, Trumbull chose to portray Washington as the steadfast and majestic general at the start of the Battle of Trenton, a pivotal engagement for colonial troops discouraged in the aftermath of several recent defeats. (Figure 8.10) The paint- ing depicts clouds in a dark, overcast sky turning pink with the rising sun juxtaposed with the general’s horse, frightened by the ongoing battle, held tightly by his aide. Washington stands with confidence, one glove off to hold a spyglass in his right hand, looking in the distance as if heeding a faraway call for victory.

Following George Washington’s celebratory visit to Charles- ton, South Carolina, in May 1791, the Charleston City Council voted to celebrate the national hero by having John Trumbull (1756-1843, USA) paint a life-size portrait of the President and hero of the Revolutionary War (1775-1783) to “hand down to posterity the remembrance of the man to whom they are so much indebted for the blessings of peace, liberty and indepen- dence.”2 Having been Washington’s aide-de-camp during the War of Independence, Trumbull chose to portray Washington as the steadfast and majestic general at the start of the Battle of Trenton, a pivotal engagement for colonial troops discouraged in the aftermath of several recent defeats. (Figure 8.10) The paint- ing depicts clouds in a dark, overcast sky turning pink with the rising sun juxtaposed with the general’s horse, frightened by the ongoing battle, held tightly by his aide. Washington stands with confidence, one glove off to hold a spyglass in his right hand, looking in the distance as if heeding a faraway call for victory.

Trumbull was pleased with “the lofty expression of his an- imated expression, the high resolve to conquer or to perish” that he captured in George Washington before the Battle of Trenton.3 His patrons in South Carolina were not, though, and rejected the portrait when he presented it to them in 1792. Speaking on behalf of the people of Charleston, South Caro- lina Congressman William Loughton Smith “thought the city would be better satisfied with a more matter-of-fact likeness, such as they had recently seen him calm, tranquil, peaceful.”4

This was not an isolated occurrence: the question of how a statesman and military hero should be represented had not been resolved to the satisfaction of artists or patrons in the eigh- teenth century, in the years both before and after the founding of the United States. As a representative democracy, the coun- try’s leaders should be depicted as a commander-in-chief who is also one of the people, many argued. But American artists unfortunately had no clear model for a “matter-of-fact likeness” in the portraits of European royalty and heads of state that they used as examples. Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641, Flanders), who was court painter to the King of England, around 1635painted Charles I at the Hunt. (Figure 8.11) The informal yet dignified stance van Dyck adopted for his image of the sovereign, a gentleman out in nature, quickly became the favorite pose for aristocrats and other dignitaries sitting for a non-ceremonial portrait. The pose still remained a standard at the time Trumbull painted George Washington before the Battle of Trenton, but, as indicated by the painting’s reception, it was not considered appropriate in a representation of the leader of a democratic nation. In addition, as the portrait was to commem- orate Washington’s visit to Charleston, townspeople thought the battle setting should be replaced with a view of that city.

Trumbull took note of his patrons’ wishes and painted another version. (General George Washington at Trenton, John Trumbull: www.flickr.com/photos/35801169@ N00/6612343749) While Washington’s pose remains virtually unchanged, Trumbull lightened the sky and inserted a view of Charleston Bay with the city on the far shore. Charleston leaders were satisfied and Trumbull promised delivery of the painting after some minor additions. The addition turned out to be the General’s horse, but reversed from the original painting, with its hindquarters prominently displayed in the space between Washington’s canary yellow breeches and his walking stick, and the distant city visible between the horse’s legs. The painting still hangs in the Historic Council Chamber of Charleston City Hall.

8.2.2 Cultural Heritage and Ethnic Identity

One important aspect of cultural and ethnic identity is shared histories or common memories. Such histories are our heritage. However, heritage is not the full history. It connects to culture and ethnicity in order to convey the full story about who we were and who we have become as a society or individual. Self or national identity is built on its foundation. Defining terms will help in understanding how each interplay to identify who we are as an individual or nation.

Christian Ellers, a popular contemporary writer on cultures, defines identity as whatever a person may distinguish themselves by, whether it be a particular country, ethnicity, religion, or- ganization, or other position. Identity is one way among many to define oneself. Ellers defines ethnicity as a group that normally has some connections or common traits, such as a common language, common heritage, and or cultural similarities. The American Dictionary defines cul- ture as the way of life of a particular people, especially as shown in ordinary behavior, habits, and attitudes toward each other or one’s moral and religious beliefs (“Culture”). We will look at these terms as they relate to artists, the visual documentarians of society.

Kimsooja (b. 1957, South Korea), a multi-disciplinary conceptual, reflects on her group identity by exploring the roots of her Korean culture. She draws upon tradition and history by selecting familiar everyday items such as fabric to communicate her message. Fabric wrapped into a bundle known as a “bottari” is commonly used to transport, carry, or store everyday objects in Korean culture. What is different is Kimsooja’s use of fabric as an art form. Since 1991, Kimsooja has used fabric, sometimes in the form of a bottari, in an on-going series, Deductive Objects, exploring Korean folk customs, daily and common activities, and her cultural background and heritage in relation to her life and experience. (Bottari Truck-Migrateurs, “Je Reviendrai”, Thierry Depagne and Jaeho Chong: http://farm8.staticflickr.com/7368/1...99de3e56_z.jpg) In this example, she photographed figures draped in Korean printed fabric that conceals their ethnicity, culture, and identity. Their identity is left to the viewer’s imagination, and their culture is left for the viewer to consider, using the print of the fabric as a clue.

A number of artists such as Kimsooja choose to communicate through their art who they are in relation to their culture and ethnicity. Their art becomes a means of validating their self-identity. Her Korean heritage represents a treasury of symbols that commemorates who they are as a people and a distinct culture with a common artistic sensibility. Their national self-image is, on one level, unambiguously defined by the convergence of territorial, ethnic, and cultural identities. The geographical conditions of the Korean Peninsula provide a self-contained nautical and continental environment with plenty of resources with which to create and be innovative. These conditions have given the people since prehistoric times a rich and unique culture to draw from and make contributions to humanity. Koreans take great pride in their homogeneous culture, and in their heritage.

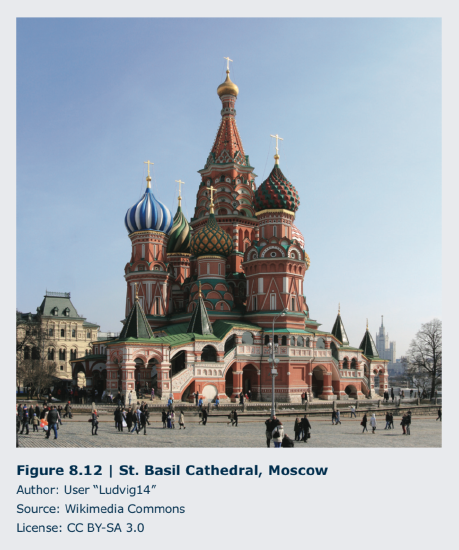

Russia, similarly self-contained, for many centuries developed cultural characteristics and ethnic identities distinctly their own, as well. Russia’s rich cultural heritage is visually stunning, from its vivid folk costumes to its elaborate religious symbols and churches. (Figure 8.12) Most Russians identify with the Eastern Orthodox (Christian) religion, but Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism are also practiced in Russia, making it a rich land of diverse ethnic groups and cultures. St. Basil’s Cathedral, located on the grounds of the Kremlin in Moscow, and hundreds of other orthodox churches symbolize Russia’s heritage; indeed, citizens proudly place pictures of the cathedrals in their homes and offices. The churches in Russia are astonishingly beautiful and very much a part of Russia’s heritage.

Ironically, then, in light of such a rich internal history, why did Russia’s rulers look to western European artists and artistic traditions to develop a new artistic identity in eighteenth century?

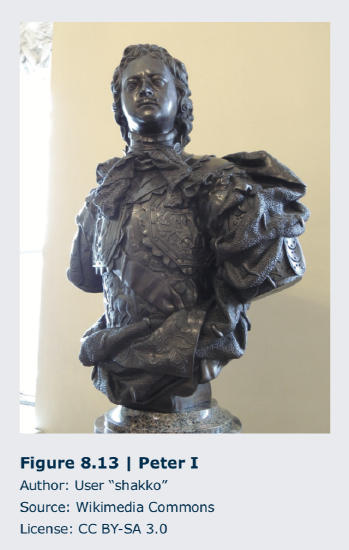

Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli (1675-1744, Italy, lived Russia), an Italian sculptor who moved to St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1716, is associated with the formation of Russia’s “new” culture. As a young artist, Rastrelli moved from his native Florence during an economic downturn to Paris in search of greater opportunities. The lavish and majestic works he created there in the late Baroque style did not earn him the success he sought, but did bring him to the attention of Tsar (and later Emperor) Peter the Great (r. 1682-1725), who lured him and his son Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli (1700-1771,France, lived Russia) to the Russia court.

Peter the Great coruled with his brother, Ivan V, and other family members until 1696, when he was twenty-four years old. At that time, Russia was still very much tied to its internal religious, political, social, and cultural traditions.Peter the Great set out to modernize all aspects his country, from the structure of the military to education for children of the nobility. The Tsar traveled widely in Western Europe, implementing governmental reforms and adopting cultural norms he saw there. France was the model for sweeping changes he had carried out in court life, fashion, literature, music, art, architecture, and even language, with French becoming the language spoken at court over the course of the eighteenth century.

Peter the Great coruled with his brother, Ivan V, and other family members until 1696, when he was twenty-four years old. At that time, Russia was still very much tied to its internal religious, political, social, and cultural traditions.Peter the Great set out to modernize all aspects his country, from the structure of the military to education for children of the nobility. The Tsar traveled widely in Western Europe, implementing governmental reforms and adopting cultural norms he saw there. France was the model for sweeping changes he had carried out in court life, fashion, literature, music, art, architecture, and even language, with French becoming the language spoken at court over the course of the eighteenth century.

Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli and his son Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli were among the painters, sculptors, and architects, then, who were instrumental in introducing to Russia the new conventions and styles that supplanted Russia’s cultural heritage and identity. For example, Carlo Rastrelli’s portrait bust of Peter the Great bears a striking stylistic resemblance to a portrait bust of French King Louis XIV (r. 1643-1715) by sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680, Italy). (Figures 8.13 and 8.14) Bernini’s bust, created during a visit to Paris in 1665, shows Louis XIV as a visionary and majestic leader who is literal- ly above vagaries of human existence such as the wind that billows his drapery. Carlo Rastrelli’s portrait of Peter the Great, completed posthumously in 1729, draws upon the same traditions dating back to images of Roman emperors such as Augustus (see Figure 3.23) of showing absolute authority through such devices as the lift of the head, eyes scanning the distance, and wearing of military armor.

His son Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli was an architect who also worked in the Baroque style. He received his first royal commission in 1721, at the age of twenty-one, but he is mainly known for opulent and impos- ing buildings he designed after Peter the Great’s death in 1725. Continuing the modernization and transformation of St. Petersburg, Francesco Rastrelli’s structures are associated with luxuriousexuberance of the Baroque, and Rus- sia’s Romanov rulers of the eighteenth century. One of Francesco Rastrelli’s most famous buildings is the Winter Palace, also bears a striking stylistic resemblance to a French palace: Ver- sailles, built for Louis XIV by architects Louis Le Vau (1612-1670, France) and Jules-Hardouin Mansart (1746-1708, France). (Figures 8.15 and 8.16)

8.2.3 Sex/Gender Identity

Kehinde Wiley (b. 1977, USA) is a contemporary portrait painter. In his work, he refers back to poses and other compositional elements used by earlier masters in much the same way that Trumbull did in his portrait of George Washington. Wiley means for his viewers to recognize the earlier work he has borrowed from in creating his painting, to make comparisons between the two, and to layer meaning from the earlier work into his own. Due to the strong contrasts between the sitters in Wiley’s paintings and those who posed for the earlier portraitists, however, this comparison often makes for a complex interweaving of meanings.

Wiley’s 2008 painting Femme piquée par un serpent, or Woman bitten by a serpent, (Femme Piquée par un Serpent, Kehinde Wiley: http://hyperallergic.com/wp-content/...ewRepublic.jpg) is based upon an 1847 marble work of the same name by French sculptor Auguste Clésinger (1814-1883, France). (Figure 8.17) When Clésinger’s flagrantly sensual nude was exhibited, the public and critics alike were scandalized, and fascinated. It was not uncommon in European and American art of the nineteenth century to use the subject of the work as justification for depicting the female nude. For example, if the subject was a moral tale or a scene from classical mythology, that was an acceptable reason for showing a nude figure. In Clésinger’s sculpture, the pretext for the woman’s indecent writhing was the snake bite, which, coupled with the roses surrounding the woman, was meant to suggest an allegory of love or beauty lost in its prime rather than simply a salacious depiction of a nude. Unfortunately, the model was easily recognized as a real person, Apollonie Sabatier, a courtesan who was the writer Charles Baudelaire’s mistress and well known among artists and writers of the day. Clésinger defended his sculpture as an artful study of the human form but, having used the features and body of a contemporary woman, his sculpture’s viewers objected to the image as too real. Wiley’s painting is the opposite: it is clearly intended to be a portrait of one individual, but he is clothed and inexplicably lying with his back to the viewer while turning to look over his shoulder. In his painting, Wiley retains the extended arms, and twisted legs and torso of Clésinger’s figure, but the sculpted woman’s thrown back head and closed eyes are replaced by the man’s turned head and mildly quizzical gaze.

Wiley takes that pose and its meanings indecency, exposure, vulnerability, powerlessness and uses them in a context that seemingly makes no sense when the subject is a fully clothed black male. Or does it? By using the conventions for depicting the female nude, Wiley asks us to examine the following: what happens when the figure is clothed with a suggestion of eroticism in the glimpse of brown skin and white briefs above his low-riding jeans; what happens when a young man gazes at the viewer with an unguarded expression of open inquisitiveness; and what happens when a black male presents his body in a posture of weakness, potentially open to attack? The artist uses these juxtapositions of meaning to challenge our notions of identity and masculinity. By expanding his visual vocabulary to include traditions in portraiture going back hundreds of years, Wiley paints a young black man at odds with contemporary conventions of (male) physicality and sexuality.

Ideas about gender identity, that is, the gender one identifies with regardless of biological sex, have developed scientifically and socially, and have in recent years become both more complex and more fluid in numerous cultures. Within other cultures, however, in addition to male or fe- male, there has traditionally been a third gender, and gender fluidity has been part of the fabric of society for thousands of years. Among the ancient Greeks, for example, a hermaphrodite, an indi- vidual who has both male and female sex characteristics, was considered “a higher, more powerful form” that created “a third, transcendent gender.”5 In Samoa, there is a strong emphasis on one’s role in the extended family, or aiga. Traditionally, if there are not enough females within an aiga to properly run the household or if there is a male child who is particularly drawn to domestic life, he is raised as fa’afafine or “in the manner of a woman.” Thus, fa’afafine are male at birth but are raised as a third gender, taking on masculine and feminine behavioral traits.

In India, those of a third gender are known as hijra, which includes individuals who are eunuchs (men who have been castrated), hermaphrodites, and transgender (when gender identity does not match assigned sex). The role of hijras is traditionally related to spirituality, and they are often devotees of a god or goddess. For example, the hijras or devotees of the Hindu goddess Bahuchara Maja are often eunuchs, having had themselves castrated voluntarily to offer their manhood to the deity. Other hijras live as part of the mainstream community and dress as women to perform only during religious celebrations, such as a birth or wedding, where they are invited to participate and bestow blessings.

Although hijras had been a respected third gender in much of Southeast Asia for thousands of years, their status changed in late nineteenth-century India while under British rule. During the twentieth century, many hijras formed their own communities, with the protection of a guru, or mentor, to provide some financial security and safekeeping from the harassment and discrimination under which they lived. In 2014, the supreme court of India ruled that hijras should be officially recognized as a third gender, dramatically changing for the better the educational andoccupational opportunities for what is estimated to be half a million to two million individuals.6

Tejal Shah (b. 1979, India) is a multi-media artist who often works in photography, video, and installation pieces. She began the Hijra Fantasy Series in 2006, (Southern Siren - Maheshwari from Hijra Fantasy Series, Tejal Shah: tejalshah.in/wp-content/theme...11/10/Image-03. jpg&w=0&h=197&zc=1) creating “tableaux in which [three hijras] enact their own personal fantasies of themselves.”7 Shah was interested in how each woman—they all had transitioned from male to female—envisions her own sexuality, separate from the perceptions and projections of others. As described by Shah, “In Southern Siren—Maheshwari, the protagonist envisions herself as a classic heroine from South Indian cinema in the throes of a passionate romantic encounter with a typical male hero.”8

In the tableau, or staged scene, Masheshwari sees herself as resplendently dressed in a blue sari, a traditional Indian draped gown, an object of admiration and desire. In this photograph and the others in the series, Shah found it noteworthy that each hijra, participating fully in the creative process, expressed feelings about herself by using visual cues and types from mainstream sources such as, in this example, Indian popular culture. How each hijra represented herself was the stuff of universal human fantasies, Shah found, regardless of sexual or gender identity: “beingbeautiful, glamourous and powerful, having a family, giving love and being loved in return.”9

8.2.4 Class

Maria Luisa of Parma was a member of the highest circles of European royalty. Born in 1751, she was the youngest daughter of Phillip, Duke of Parma, Italy, and his wife, Princess LouiseÉlisabeth of France, the eldest daughter of King Louis XV. In 1765, she married Charles IV, Prince of Asturias. She was the Queen consort of Spain from 1788, when her husband ascended to the throne, until 1808, when King Charles IV abdicated his throne under pressure from Napoleon.

Maria Luisa of Parma was a member of the highest circles of European royalty. Born in 1751, she was the youngest daughter of Phillip, Duke of Parma, Italy, and his wife, Princess LouiseÉlisabeth of France, the eldest daughter of King Louis XV. In 1765, she married Charles IV, Prince of Asturias. She was the Queen consort of Spain from 1788, when her husband ascended to the throne, until 1808, when King Charles IV abdicated his throne under pressure from Napoleon.

Royal marriages were intended to foster allegiances and cement alliances. The bride and groom generally did not meet one another until after lengthy negotiations were completed and the wedding date was near. It was not uncommon for portraits of the prospective couple to be exchanged; in addition to the descriptions by the negotiators and others, an artist’s representation was the only way to learn what one’s possible spouse looked like at a time when journeys were not easily or quickly undertaken. At the time of their engagement, Laurent Pécheux (1729-1821, French) painted this portrait of Maria Luisa (Figure 8.18) in 1765 for Princess Maria Luisa fiancé’s family.

Maria Luisa of Parma depicts the fourteen-year-old bride-to-be holding a snuffbox in her right hand containing a miniature portrait of her future husband inside its lid. This detail was a formula in formal engagement portraits: the sitter holds a gift such as this finely made and costly trinket to express appreciation and budding affection for one’s betrothed. Additionally, to demonstrate her wealthy and cultured family background, Maria Luisa is posed within an interior setting displayed in a silk brocade gown trimmed with lengths of delicate, handmade lace, a medallion of the Order of the Starry Cross suspended from a diamond-encrusted bow on her breast, and diamond stars in her powdered hair. While this is indeed a likeness of the princess, the portrait is meant to convey far more than the color of her eyes or shape of her nose. This portrait is a statement about the prestige and power she will bring to the marriage, and a congratulatory note to the groom’s family on the beauty and worth of the mutually beneficial asset they are gaining.

Maria Luisa’s dress is the exclamation point to that visual statement. She is wearing a style known as a mantua or robe a la française (in the French style), a dress for formal court occasions, of silk brocade woven into alternating bands of gold thread and pink flowers on a cream field. This very costly fabric, probably made in France, is stretched over panniers, or fan-shaped hoops made of cane, metal or whale- bone extending side-to-side. The panniers create ahorizontal but flattened silhouette that allowed the tremendous quantity of magnificent fabric required to be fully displayed. To wear such a gown was a pronouncement of one’s wealth and status, a sign of which was one’s comportment, that is, one’s bearing and behavior. And, it was indeed a challenge to stand or move with the grace expected of a highborn woman in eighteenth-century society while wearing such cumbersome, restrictive, and heavy clothing. Maria Luisa, however, is depicted as poised and charming, the perfect consort for a king.

Maria Luisa’s dress is the exclamation point to that visual statement. She is wearing a style known as a mantua or robe a la française (in the French style), a dress for formal court occasions, of silk brocade woven into alternating bands of gold thread and pink flowers on a cream field. This very costly fabric, probably made in France, is stretched over panniers, or fan-shaped hoops made of cane, metal or whale- bone extending side-to-side. The panniers create ahorizontal but flattened silhouette that allowed the tremendous quantity of magnificent fabric required to be fully displayed. To wear such a gown was a pronouncement of one’s wealth and status, a sign of which was one’s comportment, that is, one’s bearing and behavior. And, it was indeed a challenge to stand or move with the grace expected of a highborn woman in eighteenth-century society while wearing such cumbersome, restrictive, and heavy clothing. Maria Luisa, however, is depicted as poised and charming, the perfect consort for a king.

Twenty-four years after her portrait by Pécheux, Maria Luisa was thirty-eight years old and had borne ten children, five of whom were still alive, when Francisco Goya created this portrait, Maria Luisa Wearing Panniers. (Figure 8.19) , Francisco Goya was named painter to the court of Charles IV and Maria Luisa in 1789, and in celebration of CharlesIV’s ascension to the throne, created a portrait of the King, to go along with the Queen’s portrait. Neither the years nor Goya were kind to Maria Luisa. (Between 1771 and 1799, she would have fourteen living children, six of whom grew to adulthood, and ten miscarriages.)

In Goya’s depiction, she is even more richly dressed than in her earlier portrait, but her elaborate and sumptuous costume serves only to provide an unflattering contrast with the Queen’s demeanor. Goya depicts Maria Luisa with her arms awkwardly held to each side to accommodate her rigid, box-like tontillo (the Spanish variation of panniers); her plain, expressionless face is almost comically topped by a complexly constructed hat of lace, silk, and jewels. The hat represents one extravagant trend in women’s fashion of the 1780s, and Goya did paint its proliferation of textures and surfaces with great skill and sensitivity, but the contrast between the Queen’s hat and her features makes them appear even more coarse and unrefined, regardless of her wealth and class.

In Goya’s depiction, she is even more richly dressed than in her earlier portrait, but her elaborate and sumptuous costume serves only to provide an unflattering contrast with the Queen’s demeanor. Goya depicts Maria Luisa with her arms awkwardly held to each side to accommodate her rigid, box-like tontillo (the Spanish variation of panniers); her plain, expressionless face is almost comically topped by a complexly constructed hat of lace, silk, and jewels. The hat represents one extravagant trend in women’s fashion of the 1780s, and Goya did paint its proliferation of textures and surfaces with great skill and sensitivity, but the contrast between the Queen’s hat and her features makes them appear even more coarse and unrefined, regardless of her wealth and class.

What explanation could there have been for the court painter to create such an unflattering representation of Maria Luisa, Queen consort of Spain? In her years of living in her adopted country, she had not endeared herself to members of court or her subjects. Considering that the King preferred to hunt, running the country fell largely on the shoulders of Maria Luisa, who was vain and bad-tempered. Goya’s presentation does not, in fact, contradict that assessment. The emphasis on her luxurious and elegant attire and on the robe and crown to Maria Luisa’s right signaling her status as Queen consort represent that she is the individual who is literally in touch with the robes of state. This work and her engagement portrait of nearly twenty-five years earlier were not so much depictions of her as a person as they were means to communicate the power and prestige of her place and her role.

Honoré Daumier (1808- 1879, France) in 1864 painted a different sign of prestige, or lack thereof, in The Third-Class Carriage; it was one of three paintings in a series commissioned by William Thomas Walters. (Figure 8.20) The other two paintings were The First-Class Carriage and The Second-Class Carriage, the only one in the series thought to be finished. (Figures 8.21 and 8.22) Walters, an American businessman and art collector, would later found the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, with work from his collection, including these three paintings.

Honoré Daumier (1808- 1879, France) in 1864 painted a different sign of prestige, or lack thereof, in The Third-Class Carriage; it was one of three paintings in a series commissioned by William Thomas Walters. (Figure 8.20) The other two paintings were The First-Class Carriage and The Second-Class Carriage, the only one in the series thought to be finished. (Figures 8.21 and 8.22) Walters, an American businessman and art collector, would later found the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, with work from his collection, including these three paintings.

When Daumier created the works, he had been working prolifically as a painter, printmaker, and sculptor for forty years. In his lifetime, he would create ap- proximately 5,000 prints, 500 paintings, and 100 sculptures. From the beginning of his career, he was interested in the impact of industrialization on modern urban life, the plight of the poor, the quest for social equality, and the struggle for justice. He was especially known for his biting satire of politics and political figures, and his less stinging, ironic commentary on current society and events. Because of the subject matter he chose everyday people, contemporary life and the straightforward, truthful, and sincere manner in which he depicted them, Daumier is considered to be part of the Realist movement or style in art.

In The Third-Class Carriage, the artist presents four figures in the foreground, bathed in light, with numerous, less individualized figures crowded in the background. The young mother nursing her baby, an elderly woman sitting with folded hands, and a boy sleeping with his hands in his pockets encompass four generations, as well as different stages of life. Although the passengers sit near one another, they appear isolated from each other. They, including the boy, are probably traveling to or from work in the city, and both their body postures and facial expressions convey the toll of hard labor and long hours. Daumier shows compassion for these workers whose lives hold nothing but repetitious drudgery.

Forever changing the mainly agricultural society that existed in much of Europe and the United States prior to the second half of the eighteenth century, the Industrial Revolution is the start of the mechanization and manufacturing that would lead to people shifting from country to city life, and from farms to factories. While the shift to an industrial, money-based society improved the lives of many and created the middle class as we know it today, Daumier was well aware that others were being left behind and were essentially trapped in a cycle of little education, unskilled labor, and low wages.

The artist represents different life expectations based on class through the way he paints the windows and through his use of light in each of the three paintings. In The Third Class Carriage, the figures in the foreground have light shining on them from a window to the left, outside the picture plane. There are windows in the background, as well, but nothing can be seen outside of them. Daumier is implying there is nothing to be seen, especially in the case of the literally non-existent window. In The Second Class Carriage, a landscape can be seen through the window, and one of the figures looks out intently. The other three, paying no attention to the world outside, are cocooned in their winter clothes in an attempt to fend off the cold in their unheated train car. But the man who leans forward to observe the passing scenery appears to be younger and is perhaps more eager and capable of adapting to and moving upward in the world of business suggested by the bowler hat he is wearing, which at the time was associated in city life with civil servants and clerks. In First-Class Carriage, the passengers are all alert, each attending to their own business. One young woman looks out at a green landscape; considering her lightweight outerwear, it appears this is a springtime scene, which is suggested, as well, by the colorful ribbons on the two women’s fashionable bonnets. With their relaxed postures and placid, composed expressions, these first class passengers give the impression of confidence. They are more secure in themselves and their places in the world than either the second-class or third-class passengers.

8.2.5 Group Affiliation

History suggests that the quality of human survival is best when humans function as a group, allowing for collective support and interaction. Social psychological research indicates that people who are affiliated with groups are psychologically and physically stronger and better able to cope when faced with stressful situations. Gregory Walton, a social psychologist who studies group interaction, has concluded that one benefit individuals receive is the satisfaction of belonging (to a group, culture, nation or) to a greater community that shares some common interests and aspirations. The unity of groups is achieved through members’ similarities or their having experiences based on the history that brought them together.

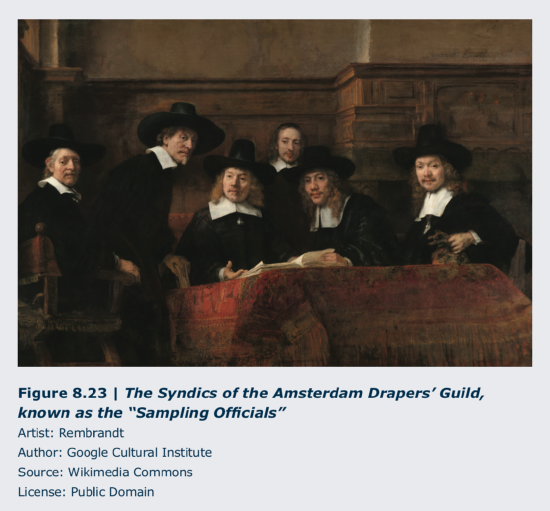

Artists throughout history have been associated with groups, movements, and organizations that protect their interests, forward their cause, or promote them as a group or as individuals. The most visible groups during the Renaissance period in Italy, for example, were people belonging to the Catholic Church and other religious organizations, wealthy merchant families, civic and government groups, and guilds, including artists’ guilds. (Figures 8.23 and 8.24)

8.2.6 Personal Identity

The city of Palmyra, in modern Syria, had long been at the crossroads of Western and Eastern political, religious, and cultural influences, as it was a caravan stop for traders traveling the Silk Road between the Mediterranean and the Far East. In the first century CE, the city came under Roman rule and under the Romans, the city prospered, and the arts flourished. Following a rebel- lion by Queen Zenobia of Palmyra in 273 CE, Roman Emperor Aurelian destroyed the city, ending the period of Roman control.

The Palmyrenes, or people of Palmyra, built three types of elaborate, large-scale monuments for their dead called houses of eternity. The first was a tower tomb, some as high as four stories. The second was a hypogeum, or underground tomb, and the third was a tomb built in the shape of a temple or house. All were used by many generations of the same extended family and were located in a necropolis, a city of the dead, what we today call a cemetery. Inside the tombs were loculi, or small, separate spaces, each of which formed an individual sarcophagus, or stone coffin. Inside the opening to the tomb, the first sarcophagus held the remains of the clan’s founder; it was often faced with a stone relief sculpture depicting him as if attending a banquet and inviting others to join him. Surrounding the founder in the loculi, on the face of each family member’s sarcophagus would be a relief portrait of each person interred there. (Loculi: romeartlover. tripod.com/Palmyra5.html)

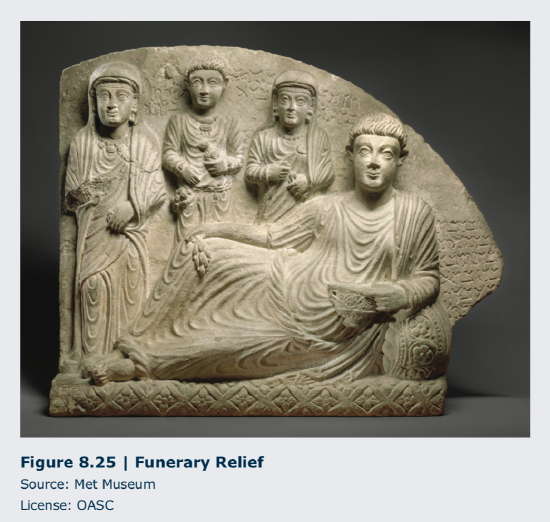

This stele, a portrait of a father, his son, and two daughters, dates to between 100 and 300 CE, sometime during the era of Roman rule. (Figure 8.25) The man is reclining on a couch decorated with flower motifs within circles and diamonds. He holds a bunch of grapes in his right hand and, in his left, a wine cup decorated with flowers similar to those on the couch. His two daughters flank his son in the background; the son holding grapes and a bird. The son and daughters all wear neck- laces. Additionally, the daughters wear pendant earrings and brooches holding the drapery at their left shoulders. The chiton, or tunic, and himation, or cloak, that each daughter wears has some affinities with Greco-Roman types of clothing, but the style of the ornamented veil covering their heads is a local type of garment, based on Parthian, or Persian, styles. Also wearing local garments, the two males wear a loose fitting tunic and trousers, each with a decorative border. The fine fabrics indicated by the embellished borders of both men and women’s clothing indicate goods and wealth amassed from trade, as does the abundant use of precious metals and gems in the variety of jewelry adorned by the Palmyrenes. Thus, the stele is a blend of Greco-Roman and Palmyrene (and larger Parthian) styles and cultural influences.

This stele, a portrait of a father, his son, and two daughters, dates to between 100 and 300 CE, sometime during the era of Roman rule. (Figure 8.25) The man is reclining on a couch decorated with flower motifs within circles and diamonds. He holds a bunch of grapes in his right hand and, in his left, a wine cup decorated with flowers similar to those on the couch. His two daughters flank his son in the background; the son holding grapes and a bird. The son and daughters all wear neck- laces. Additionally, the daughters wear pendant earrings and brooches holding the drapery at their left shoulders. The chiton, or tunic, and himation, or cloak, that each daughter wears has some affinities with Greco-Roman types of clothing, but the style of the ornamented veil covering their heads is a local type of garment, based on Parthian, or Persian, styles. Also wearing local garments, the two males wear a loose fitting tunic and trousers, each with a decorative border. The fine fabrics indicated by the embellished borders of both men and women’s clothing indicate goods and wealth amassed from trade, as does the abundant use of precious metals and gems in the variety of jewelry adorned by the Palmyrenes. Thus, the stele is a blend of Greco-Roman and Palmyrene (and larger Parthian) styles and cultural influences.

Coupled upon many Palmyrenes grave steles are inscriptions of text in both Aramaic and Latin that give the person’s name and genealogy, markers of distinctive individual and family traits. While many of the depictions of the frontal-facing, wide-eyed figures a defining feature of Palmyrene art show little individualization of features, the coupling with such inscriptions are evident signs that each stele was intended to denote the characteristics of the person entombed within. The figures actively engage the viewer, and provide the reminder that personal identity is an amalgamate of individual, socio cultural, spiritual, and historical influences.

In July 2015, the city of Palmyra, its people, and its art were again in danger. In April of 2015, Islamic State (ISIS) forces overtook the 3,000-year-old Assyrian city of Nimrud and destroyed its buildings and art. On May 21, 2015, ISIS overtook the city of Palmyra, inducing fear that they would destroy buildings and art there as they did in Nimrud. On July 2, 2015, ISIS was reported to have destroyed grave markers similar to the one discussed here. (Grave Marker Reliefs, http:// www.timesofisrael.com/is-destroys-iconic-lion-statue-at-syrias-palmyra-museum/) They lined up six bust-length reliefs of people who lived in Palmyra nearly 2,000 years ago, and smashed them, obliterating the visual and written record of each person. So many have had their portraits made for posterity with the hopes of staying alive, against the odds. And, this is why we need art: it gives us memories of ourselves and our deeds, who we identify with, and how we identify others.

- George and Martha Washington: Portraits from the Presidential Years, exhibition, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC, 1999, accessed July 6, 2015, http://www.npg.si.edu/exh/gw/trenton.htm

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Aileen Ajootian, “The Only Happy Couple: Hermaphrodites and Gender” in Naked Truth: Women, Sexuality and Gender in Classical Art and Architecture, ed. Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Claire L. Lyons (New York: Routledge, 1997), 228.

- http://www.npr.org/sections/parallel...ender-in-india

- Tejal Shah, Artist Statement, Hijra Fantasy Series, accessed July 7, 2015, http://tejalshah.in/project/what-are-you/hijra- fantasy-series/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.