6.6: COMMUNICATION

- Page ID

- 10147

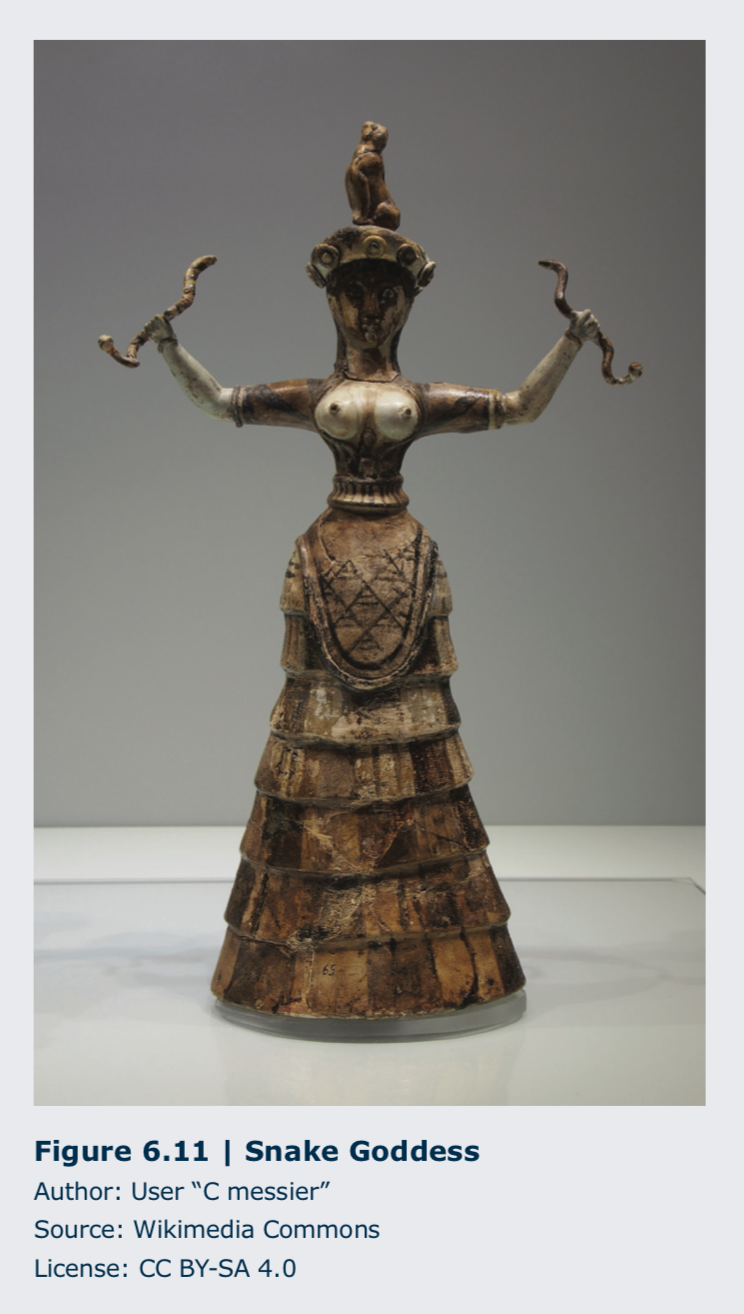

In past societies in which art played a central role, people communicated through their creativity. In societies where many people were illiterate, they understood and learned more from symbolism and images than from words. One such example is the Snake Goddess discovered by archaeologist Arthur Evans and his team in 1903 at the Palace of Knossos on the island of Crete. (Figure 6.11) Part of the Minoan civilization (c. 3650-c. 1,450 BCE), this deity is believed to be a fertility symbol, also known as a “Mother Goddess,” a reli- gious symbol that appears from prehistoric eras until the Roman Empire. The snake held in each of the figure’s upraised hands is associated with fertility and symbolizes the renewal of life due to the fact that it periodically sheds its skin. The object tells us about the type of culture from which it is derived, articulating their beliefs, traditions, and customs. For the Minoans, there was no need to explain or interpret this image because it was easily understood by their community.

For Chinese art, different periods in history have given way to different meanings attributed to its imagery. Although numerous textiles, calligraphy, ceramics, paintings, sculptures, and other objects and works from China are thousands of years old, the idea of grouping them under the description of “Chinese art” has a short history. In this sense, art in China is not really that old. This is because the vast majority of people in China did not see the artifacts that are the artistic heritage of that country before the twentieth century when the Nantong Museum, the first built by the Chinese and not colonial occupiers, opened in 1905 despite the existence of a sophisticated tradition of creating art and of collecting and showing art to the elite.

Categorizing Chinese art allowed statements to be made about the art and people. The var- ious ways in which different meanings have been read into Chinese art at different periods of time is well illustrated in this jade gui tablet. (Jade Tablet: http://culture.teldap.tw/culture/ images/collection/20120807_NPM/jade04.jpg) A gui is a ritual scepter, held by a ruler during ceremonies as a symbol of rank and power. According to researcher Tsai Wen Hsiung, the his- tory of using jade can be traced back seven thousand years. Looking at jade plaques unearthed from the Stone Age and Neolithic period, it is evident that the Chinese people were the first to carve jade for ornaments. This jade tablet is from the Late Shandong Longshan Culture (c. 2650-2050 BCE). Located in Shandong province, it was the last Neolithic jade culture in the Yangtze Valley River region, a land area rich in resources. The tablet is one of a large number of artifacts made from jade in that creative era, many of which replicated weapons and tools. Jade was the most precious material available in the Yangtze region at the time the jade gui tablet was made.

The tablet represents the excellent manufactured craftsmanship of the Shandong Longshan culture. The stone has a yellow tone with grey and ochre natural coloring resulting from aging over time. In low relief slightly below the middle of the tablet is a stylized face of a god shown in a typically flattened view. (Detail of Jade Tablet: http://culture.teldap.tw/culture/images/ collection/20120807_NPM/jade05.jpg) There is an eighteenth-century inscription by a Chinese emperior who provides an explanation of the decoration. According to art historian Chang Li-tuan, the tablet was originally plain, but during the Ch’ien–lung reign two poems from different years were engraved on it; the last engraving in 1754 was by the Ch’ien–lung Emperor. The stone with its décor of symbolic images and incriptions represents the Chinese love of antiquity, depicting

a people uniquely proud of interpreting their history. It also shows us the tradition in Chinese art of contributing to the meaning of a work by adding words and imagery to it over time. In doing so, both the symbolism and the status of the object are enhanced.

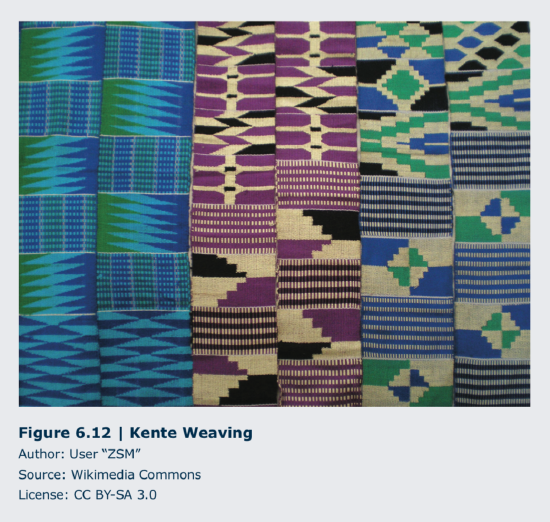

A more modern use of communicating through symbols in art can be found among the Ashanti people of Ghana, West Africa, and the Kente cloth woven by them and others in the region, including the Ewe people. Using silk and cotton, the cloth is woven on specially designed looms in fourinch strips that are then sewn together. (Figure 6.12) Kente cloth was traditionally worn by kings during special ceremonies. The patterns and symbols woven into the cloth conveyed highly individualized messages that could not be reproduced by the weavers for any other individuals. Colors conveyed mood, with darker shades associated with grieving and lighter shades with happiness. Although the cloth was originally for political leaders, the design was not meant to convey a political message: it represented the culture’s spiritual beliefs in symbols and colors.

In his conceptual art, Mel Chin (b. 1951, USA) does make a political statement. For example, he examines the psychological and social issues of imperialism in his black nine-by-fourteen-foot spider. In the stomach of the giant, intimidating spider is a glass case containing an 1843 china teapot on a silver serving tray. (Cabinet of Craving, Jesse Lott and Madeline O’Connor: http:// melchin.org/oeuvre/cabinet-of-craving) The sculpture symbolizes the destructive co-dependence of empires, depicting the English craving for tea and porcelain during the Victorian era and the Chinese desire for silver that led to the Opium Wars (1839-42, 1856-60). Although Chin takes an indirect approach in making his political statement, it is nevertheless powerful.