5.2: SOCIO-CULTURAL CONTEXTS

- Page ID

- 10137

5.2.1 Historical Context

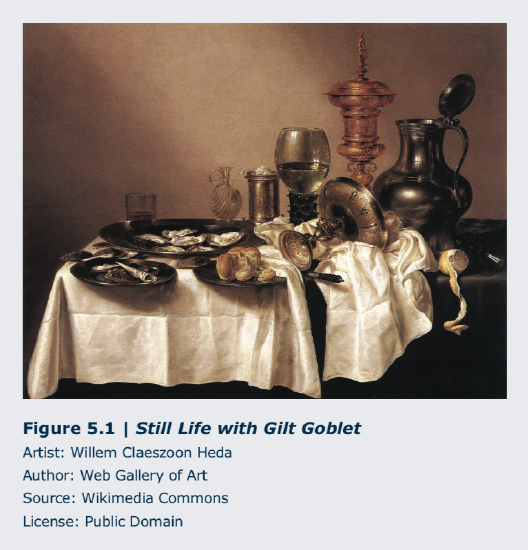

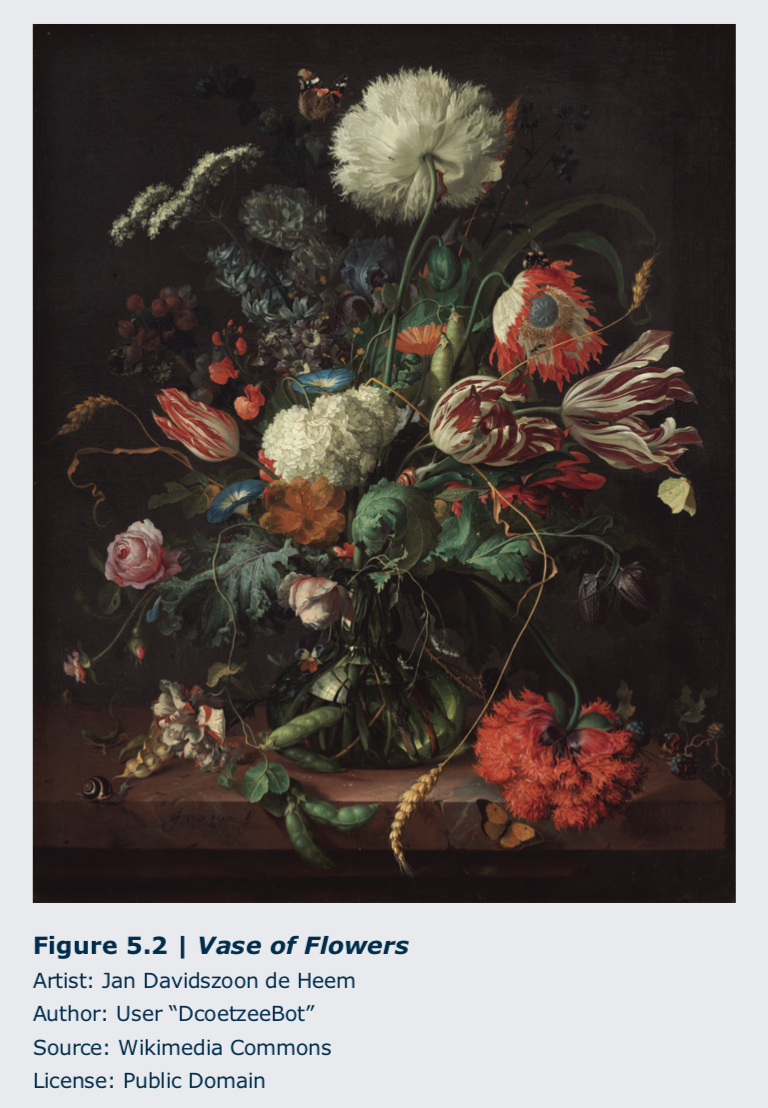

We can learn about the historical context to help us interpret the content and understand the meaning of two seventeenth-century Dutch paintings. Willem Claesz. Heda (1594-1680, Netherlands) created Still Life with a Gilt Cup in 1635, and Jan Davidsz. de Heem painted Still Life with Flowers around 1660. (Figures 5.1 and 5.2) Heda lived in his native Haarlem his entire life; de Heem was born in Utrecht but traveled in the Netherlands and then lived in Antwerp for the majori- ty of his career, c. 1635 to 1667. He briefly returned to Utrecht but settled back in Antwerp in the 1670s where he remained until his death.

Although depicting different types of things, each of these paintings is a still life, an arrangement of objects both made by humans and found in nature, such as flowers, fruit, insects, sea creatures, and animals from the hunt. A still life falls into a subject category known as genre subjects or scenes of everyday life. Both Heda and de Heem specialized in painting still lifes that were beautifully arranged and stunningly lifelike. Each was well known for his ability to depict a variety of textures and surfaces often displayed side-by-side, as we can see here, to create a dazzling and sumptuous visual array.

Although depicting different types of things, each of these paintings is a still life, an arrangement of objects both made by humans and found in nature, such as flowers, fruit, insects, sea creatures, and animals from the hunt. A still life falls into a subject category known as genre subjects or scenes of everyday life. Both Heda and de Heem specialized in painting still lifes that were beautifully arranged and stunningly lifelike. Each was well known for his ability to depict a variety of textures and surfaces often displayed side-by-side, as we can see here, to create a dazzling and sumptuous visual array.

There are a number of things going on in the Netherlands in the 1600s known as the Dutch Golden Age that can help explain why Heda and de Heem included some of the objects in their paintings. What is today the Netherlands (or Holland) and Belgium were together ruled first by the Dukes of Burgundy, the Burgundians, beginning in 1433 and then by Charles V of the Habsburg family in 1506. Charles V left the Netherlands in 1515, however, to become King of Spain. Tension created by family members who remained in place to rule led to friction with the Dutch and eventually to revolt beginning in 1566. At the same time, the Protestant Reformation that originated in Wittenberg, Germany, under Martin Luther in 1517 had spread through much of northern Europe, including parts of the Netherlands. Followers of the new Protestant faith were at first tolerated by the Catholic Spanish rulers, but they were soon treated as heretics, and their faith was seen as a rebellion to be crushed. William I, Prince of Orange, a Dutch nobleman, turned away from his position in the court of the Habsburg rulers to lead his country into the Dutch War for Independence from Spain, more commonly known as the Eighty Years War (1568-1648). In 1581, the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands were declared independent, forming what we still know as Holland today. The southern area that remained under Catholic Spanish rule was known as Flanders and is modern Belgium. Fighting continued on and off between the Dutch and Spanish until 1618 when they both became embroiled in a larger European War known as the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). With the signing of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the Spanish crown officially acknowledged the republic of Holland.

In the midst of this ongoing turmoil over politics and religion, as well as decades of disruption and destruction caused by war, the Netherlands also experienced a time of tremendous economic growth, revolutionary scientific exploration, dominance in worldwide trade, and flourishing of the arts. The rise of the merchant class (equivalent to today’s middle class) led to the spread of education and wealth among new segments of society. Their knowledge of and appreciation for art, along with their discretionary income, in turn led to increased patronage. Patrons of art were not looking to purchase sculptures and paintings for churches, however, as Protestants do not embellish their houses of worship; they do not adorn the word of God as found in the Bible. This led to interest in new subjects in painting, such as genre and still life painting, as well as landscapes, city views, portraits, and religious subjects in works meant to hang in the home.

The subject of Heda’s painting, Still Life with a Gilt Cup, is ostensibly the remains of a meal of oysters and bread, but it is even more about all the objects accompanying the food. (Figure 5.1) The tin plates and open-lidded pewter pitcher are relatively simply fashioned and could have been made by local craftsmen. But the remaining items, including a spiral ribbed clear glass cruet for oil or vinegar behind the tin bowl of oysters, the green glass wine römer, or goblet, decorated with prunts (applied blobs of molten glass, here drawn into points), and the tall, heavily ornamented, and gilded vessel topped by a lid with a figure of a warrior, are all luxury goods. They indicate wealth and good taste, and they allude to Holland’s importance as a nation of traders who import beautiful objects from around the world.

The subject of Heda’s painting, Still Life with a Gilt Cup, is ostensibly the remains of a meal of oysters and bread, but it is even more about all the objects accompanying the food. (Figure 5.1) The tin plates and open-lidded pewter pitcher are relatively simply fashioned and could have been made by local craftsmen. But the remaining items, including a spiral ribbed clear glass cruet for oil or vinegar behind the tin bowl of oysters, the green glass wine römer, or goblet, decorated with prunts (applied blobs of molten glass, here drawn into points), and the tall, heavily ornamented, and gilded vessel topped by a lid with a figure of a warrior, are all luxury goods. They indicate wealth and good taste, and they allude to Holland’s importance as a nation of traders who import beautiful objects from around the world.

We are not meant to look at this feast for the eyes and simply congratulate ourselves on our success and prosperity, though. The fact is the feast is over, and all we have here are the remains of what has too quickly passed. The richly decorated silver berkemeier, a wide-mouthed drinking vessel with a slender stem, is overturned. The oysters are a delicacy that retain their freshness and appeal only briefly, and the lemon, while beautiful, is actually bitter and will soon dry out. These are reminders that life is fleeting. No matter what material riches and comforts one accumulates on earth, it is more important to prepare one’s soul for life everlasting.

In a similar fashion, in Still Life with Flowers de Heem sets before us, teeming with life and in abundant disarray, the beauty and bounty of nature. (Figure 5.2) But he also shows the swift passing of the seasons by depicting flowers, fruits, and vegetables that bloom and ripen throughout the year. The tulips from highly prized and costly bulbs imported by the Dutch from the Ottoman Empire (modern Turkey) honeysuckle, roses, carnations, peas, grapes, and corn introduced to Europe from the Americas are among the profusion of colors and forms that de Heem unrealistically depicts as all in season at the same time. The viewer would instead know that long before the orange carnation blossomed in the fall, the blood-red striped tulip would have withered in the spring. De Heem is reminding us in this vanitas (Latin: vanity) still life of our own mortality and the transience of life in the face of certain death.

Both paintings’ messages reflect the importance in the Protestant faith, as practiced in Holland at the time, of the believer’s direct connection to God without the need for intercessors. The faithful do not need the word of God to be interpreted for them, and the messages of God are everywhere. Both paintings are celebrations of riches and pleasures of life, but they are also reminders of its brevity and the unimportance of earthly possessions and human achievements in the face of eternity. So, while the works demonstrate the Dutch viewers’ pride in themselves and their young nation’s accomplishments in the face of tremendous obstacles, they also carry a word of caution and a reminder to be vigilant.

5.2.2 Social Context

Lilly Martin Spencer (1822-1902, USA) painted Conversation Piece around 1851-1852. (Figure 5.3) A genre painting, it depicts an everyday scene of a mother holding her infant in her lap while the father stands beside them playfully dangling some cherries above the baby’s eager grasp. It is a quiet scene of family life, a moment of contentment and peace, with the dining table not yet cleared after a meal adding an even greater sense of intimacy and informality. Spencer was the only prominent female painter at that time in the United States, and the majority of her works are narrative genre pieces such as this one. They are scenes of domestic life, often suggesting a story told through the setting, the arrangement and gesture of the figures, and their facial expressions.

Elements in Spencer’s work often seem to reflect her personal life. The artist depicted herself and her husband in Conversation Piece, as she did in many of her paintings. Not only was it unusual that she was a successful professional painter, when she married Benjamin Rush Spencer, he took on the household duties and aided his wife in pursuing her career. Over the course of their long (and what is believed to be happy) marriage, while also bearing thirteen children and raising seven to adulthood, Spencer remained the breadwinner of the family.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, a number of changes had been introduced into American industry and commerce that had far reaching effects on the roles women, men, and children played in the home and in the labor force. The advent of new machinery and production methods in the textile industry, for example, generated a need for mill workers that in turn fostered the growth and spread of urban centers. At the same time, both those who owned and managed the mill factories as well as those who worked in them became part of a wage-based economy, and the demand for goods and services to support them rose accordingly. In New England, the majority of the mill workers were young women who had been recruited from rural areas; the wages they earned were often saved in anticipation of marriage or to supplement their family’s income. But critics feared the economic and social independence these young women gained would turn them against the often hard and isolated farm lives they left behind, and indeed many chose not to re- turn. The greatest apprehension, however, was these women would turn away from their rightful place in the private sphere of home.

The growing industrialism of American society impacted men and their roles within and out- side the home, as well. Men primarily worked in the public sphere, that is, outside the home in areas such as manufacturing, business, or commerce. Their roles were in sharp contrast to the domestic duties and roles of wife and mother played by women. This separation of obligations and expectations led to rigid gender roles in which both women and men were contained. The roles confined the woman to the protective environment of home, while the man sheltered her as he faced the harsh demands outside.

In Spencer’s painting, the woman represents the feminine ideal of a nurturing and content mother. But rather than showing a father who holds himself apart from the womanly, domestic sphere—as was far more common at the time Spencer depicts the man in an equally caring and warm role. An oval is formed by the mother’s bent head and arm which extends from her hand supporting the baby’s head through the baby’s upraised arm to the father’s bent arm, his bowed head, and his left arm resting on the back of the mother’s chair. At odds with many at the time who believed men and women existed in separate spheres, Spencer draws the family into one circle.

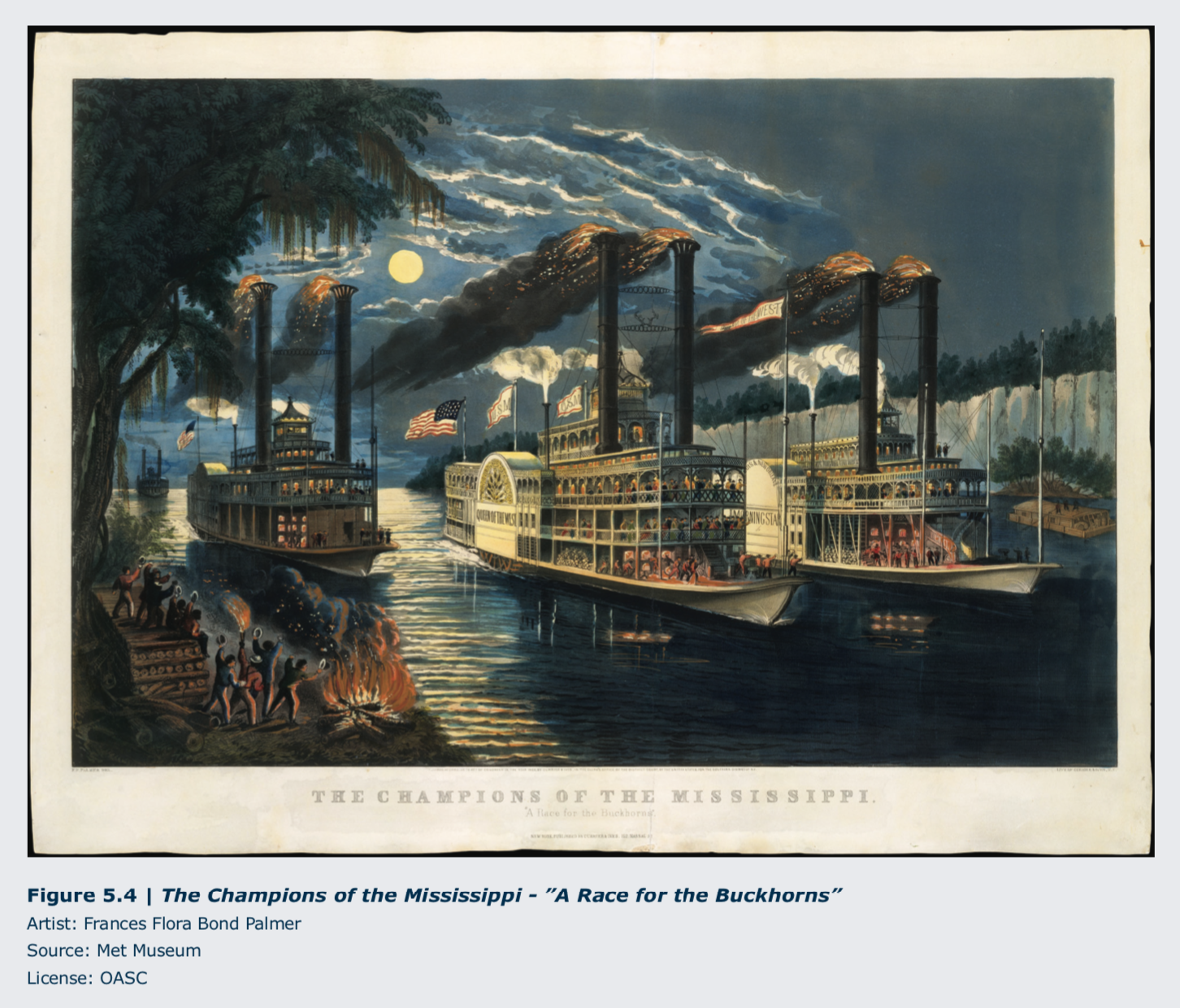

American industrialism worked hand-in-hand with American ingenuity. Steamboat routes on the Mississippi River and its tributaries substantially contributing to the growth of settlements and cities from New Orleans to Pittsburgh began in 1811. The first steamboat to make that run was the New Orleans designed by Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston, both key figures in the development of steamboat design and travel. As would be the case with the thousands of steamboats that would traverse the Mississippi over the next century, it was made of wood and propelled by a paddlewheel that was powered by a steam engine; the steam was made by heating water in boilers which had to be watched to avoid pressure building to the point of explosion, a very real and constant danger. In attempts to better travel time between landings or by engaging in races with other steamboats, however, it was not uncommon for the engineer to stoke the fires while keeping the boilers’ safety valves closed, allowing steam pressure to build past safe levels.

Although 230 boats were destroyed due to boiler explosions between 1816 and 1848 with the loss of nearly 1,800 lives, one of the great attractions of steamboat travel remained its speed.1 The excitement and the danger of a steamboat race are captured in a print published by Currier & Ives in 1866, The Champions of the Mississippi: A Race for the Buckhorns. (Figure 5.4) Na- thaniel Currier (1813-1888, USA) and his brother-in-law James Merritt Ives (1824-1895, USA) formed the company Currier & Ives in 1857. They published black-and-white and hand-colored lithographs on numerous subjects meant to appeal to a broad spectrum of the American public, including landscapes, genre scenes, portraits, depictions of politics and current events, and the latest innovations in science, industry, and the arts.

Although 230 boats were destroyed due to boiler explosions between 1816 and 1848 with the loss of nearly 1,800 lives, one of the great attractions of steamboat travel remained its speed.1 The excitement and the danger of a steamboat race are captured in a print published by Currier & Ives in 1866, The Champions of the Mississippi: A Race for the Buckhorns. (Figure 5.4) Na- thaniel Currier (1813-1888, USA) and his brother-in-law James Merritt Ives (1824-1895, USA) formed the company Currier & Ives in 1857. They published black-and-white and hand-colored lithographs on numerous subjects meant to appeal to a broad spectrum of the American public, including landscapes, genre scenes, portraits, depictions of politics and current events, and the latest innovations in science, industry, and the arts.

The firm of Currier & Ives hired well-known artists of the day to create the drawings from which their lithographic prints were made. The artist who drew the Champions of the Mississippi was Frances Flora Bond Palmer (1812-1876, USA). Palmer, like Lilly Martin Spencer, supported her family as a full-time artist. Palmer produced hundreds of original drawings in the seventeen years she worked for Currier & Ives, more than any other artist they employed. She printed and hand-colored many of her own works, as well, parts of the lithographic process generally reserved for artists in the firm with less training and expertise. For example, the prints were usually paint- ed in an assembly line, with one artisan applying a single color and passing the work on to the next for another color. That Palmer took part in all phases of creating the prints was an indication of her great skill and versatility.

As was the case with the majority of scenes Palmer created, she did not witness the race be- tween the steamboats Queen of the West and Morning Star or the cheering crowd on the shore. She depicted numerous such scenes, however, as competitions such as this were commonplace and prints commemorating them were popular and sold well. The races and the steamboats were a source of pride and a celebration of American ingenuity, competitiveness, and success. For those who owned a print such as The Champions of the Mississippi, the vast majority of whom had never seen the river or a steamboat competition, it represented the open possibilities of America’s greatest waterway and indomitable spirit. As described by Mark Twain, who grew up in a town on the river’s shore and spent four years as a riverboat pilot (1857-1861), there was a nearly magical quality to the allure and excitement of life on the river, especially when a steamboat race was coming. He related in his memoir Life on the Mississippi (1883):

In the “flush times” of steamboating, a race between two notoriously fleet steamers was an event of vast importance. The date was set for it several weeks in advance, and from that time forward, the whole Mississippi Valley was in a state of consuming excitement. Politics and the weather were dropped, and people talked only of the coming race.

The chosen date being come, and all things in readiness, the two great steamers back into the stream, and lie there jockeying a moment, and apparently watching each other’s slightest movement, like sentient creatures; flags drooping, the pent steam shrieking through safety-valves, the black smoke rolling and tumbling from the chimneys and darkening all the air. People, people everywhere; the shores, the house-tops, the steamboats, the ships, are packed with them, and you know that the borders of the broad Mississippi are going to be fringed with humanity thence northward twelve hundred miles, to welcome these racers.2

5.2.3 Personal or Creative Narrative Context

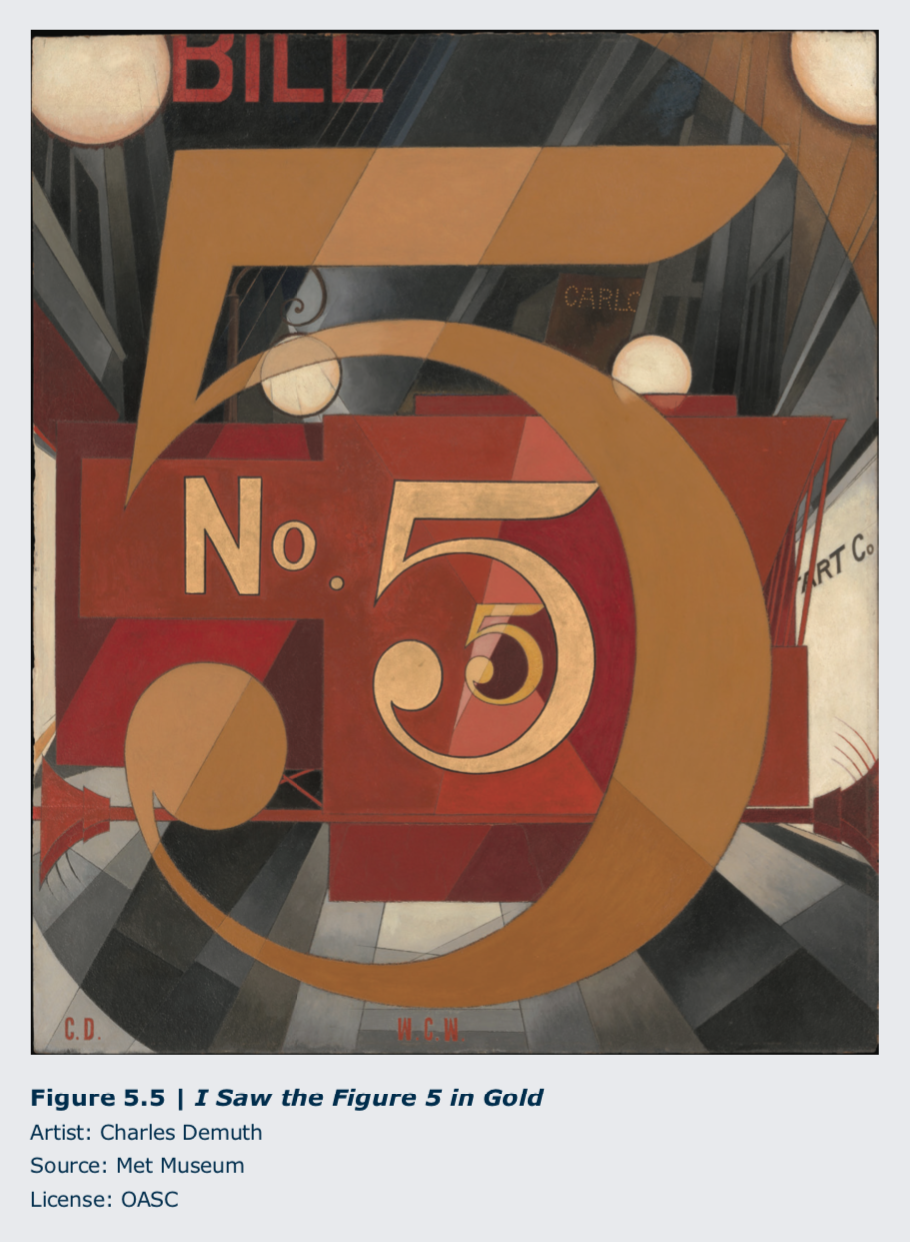

Charles Demuth (1883-1935, USA) painted The Figure 5 in Gold in 1928. (Figure 5.5) Demuth met poet and physician William Carlos Williams at the boarding house where they both lived in Philadelphia while studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Demuth’s painting is one in a series of portraits of friends, paying homage to Williams and his 1916 poem “The Great Figure”:

Among the rain and lights I saw the figure 5 in gold on a red firetruck moving tense unheeded to gong clangs siren howls and wheels rumbling through the dark city.

Williams described the inspiration for his poem as an encounter with a fire truck as it noisily sped along the streets of New York, abruptly shaking him from his inner thoughts to a jarring awareness of what was going on around him. Demuth chose to paint his portrait of Williams not as a likeness but with references to his friend, the poet. The dark, shadowed diagonal lines radiating from the center of his painting, punctuated by bright white circles, capture the jolt of the charging truck accompanied by the clamor of its bells. The accelerating beat of the figure 5 echoes the pounding of Williams’s heart as he was startled. It was the sight of the number in gold that Williams was first aware of at the scene, and Demuth uses the pulsing 5 to symbolically portray his friend, surrounded by the rush of red as bright as blood with his name, Bill, above as if flashing in red neon.

For Demuth, that connection between his friend and his poetry told us far more about who Williams was than his physical appearance. A traditional portrait would show us what Williams looked like, but Demuth wanted to share with the viewer the experience of the poem the artist closely identified with his friend so that we would have an inner, deeper understanding of the po- et. Demuth gave us his personal interpretation of Williams through the story, the narrative, that he tells us with the aid of “The Great Figure.”

For Demuth, that connection between his friend and his poetry told us far more about who Williams was than his physical appearance. A traditional portrait would show us what Williams looked like, but Demuth wanted to share with the viewer the experience of the poem the artist closely identified with his friend so that we would have an inner, deeper understanding of the po- et. Demuth gave us his personal interpretation of Williams through the story, the narrative, that he tells us with the aid of “The Great Figure.”

Georgia O’Keeffe gives us a portrait of the American landscape in a similar way in her painting Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue from 1931. (Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue, Georgia O’Keeffe:http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/.../search/488694) Throughout the nineteenth century and into the first decades of the twentieth century, the majority of artists depicted the American land through its mountains and forests, farmlands and prairies, rivers and waterfalls: the vast stretches, immense heights, bounty, variety, and majesty of the seemingly endless continent. In this painting, however, O’Keeffe chose to portray the beauty of the United States not through its fertile grasslands or rocky peaks but in the austerity and simplicity of the desert of the American Southwest that she had come to appreciate, as symbolized by the sharp lines of a bleached cow’s skull set against patriotic red and blue.

O’Keeffe was born in 1887 near Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. After studying art and working as an art teacher in several areas of the United States, including Chicago, Illinois, Amarillo, Texas, and Columbia, South Carolina, O’Keeffe moved to New York City in 1918.

Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946, USA), a photographer, publisher, and art gallery owner who was instrumental in introducing audiences to and helping them appreciate European and American modernist art in this country in the first decades of the twentieth century, had exhibited O’Keeffe’s drawings in his gallery 291 in 1917. The following year she accepted his offer of support so that she could devote herself to painting full-time. After more than ten years in New York, depicting streets and buildings of the city and at the Stieglitz family home on Lake George in upstate New York, O’Keeffe decided to spend the summer of 1929 with friends in Santa Fe and Taos, New Mexico.

Painted after that trip, Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue shows the artist providing a contrast to traditional and popular landscape views. She is inviting the viewer to contemplate how nature can be daunting and uninviting and to remember the flinty strength of the pioneers who moved across and settled in the demanding climate and terrain of the Southwest. The harshness of that life can be seen in the jagged lines of splintered bone in the skull, a reminder of inevitable death— similar to a seventeenth-century Dutch vanitas piece such as de Heem’s Vase of Flowers. But, the skull was also an object representing life to O’Keeffe:

To me they are as beautiful as anything I know. To me they are strangely more living than the animals walking around...The bones seem to cut sharply to the center of something that is keenly alive on the desert even tho’ it is vast and empty and untouchable—and knows no kindness with all its beauty.3

5.2.4 Political Context

As was the case with the painting Pear Blossoms by Qian Xuan (Figure 1.10), Bamboo and Rocks by Li Kan (1245-1320, China) was painted during the Yuan Dynasty when the Mongols ruled China. (Figure 5.6) There are similarities but also important differences between the works. Pear Blossoms was painted in 1280, shortly after the Mongols took power, and Bamboo and Rocks was painted nearly forty years later in 1318. During that period, the Mongolian leaders made substantial changes in the government, thrusting out those in imperial power and scholar officials, including painters. Those who had been at the top of the social and political hierarchy were now turned away from government positions and looked upon with distrust and distaste.

Although the Mongols appreciated Chinese painting and artists were commissioned to make (or appointed to produce) works for those in power, many were unwilling to paint for the foreign leaders. Kan’s painting is interpreted as a reflection on China, its people, and its traditions under Mongolian rule. Bamboo and Rocks is a pair of scrolls painted with ink and color on silk meant to be hung side-by-side. Unlike Pear Blossoms, which is a scroll meant to be unrolled in approximately twelve-inch segments on a table then rolled again to reveal the next segment and finally stored away be- tween viewings, Bamboo and Rocks would remain in view hanging on a wall. Both are ink paintings capturing the simplicity of beauty in nature. But the objects depicted also have symbolic meaning going back to ancient Chinese culture. Bamboo symbolizes virtue, grace, and resilience, while rocks symbolize strength and power to endure. In Kan’s painting, their contrasting forms, low and curvilinear against upright and angular, balance each other. The artist is indicating that during the Yuan Dynasty, under the rule of the Mongol, the Chinese people would be like bamboo; they would bow but not break in the un- certain climate of the rocky landscape of occupation.

Although the Mongols appreciated Chinese painting and artists were commissioned to make (or appointed to produce) works for those in power, many were unwilling to paint for the foreign leaders. Kan’s painting is interpreted as a reflection on China, its people, and its traditions under Mongolian rule. Bamboo and Rocks is a pair of scrolls painted with ink and color on silk meant to be hung side-by-side. Unlike Pear Blossoms, which is a scroll meant to be unrolled in approximately twelve-inch segments on a table then rolled again to reveal the next segment and finally stored away be- tween viewings, Bamboo and Rocks would remain in view hanging on a wall. Both are ink paintings capturing the simplicity of beauty in nature. But the objects depicted also have symbolic meaning going back to ancient Chinese culture. Bamboo symbolizes virtue, grace, and resilience, while rocks symbolize strength and power to endure. In Kan’s painting, their contrasting forms, low and curvilinear against upright and angular, balance each other. The artist is indicating that during the Yuan Dynasty, under the rule of the Mongol, the Chinese people would be like bamboo; they would bow but not break in the un- certain climate of the rocky landscape of occupation.

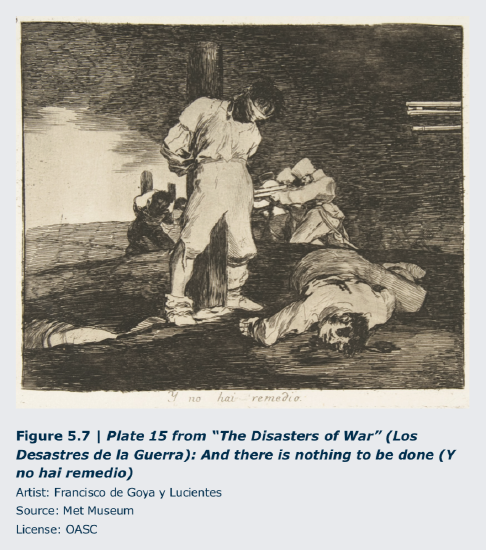

Francisco de Goya y Lucien- tes (1746-1828, Spain) was court painter to King Charles IV from the beginning of his reign in 1789 until Napoleon ousted Charles from his throne in 1808 during the French invasion of Spain. Goya was hired the same year to make a visual re- cord of the bravery of the Spanish people against the onslaught of the French invaders. The impact of what Goya saw, however, changed the direction and tone of the series of prints he made from the unflinching courage of his fellow citizens to despair over the barbarous atrocities committed and merciless suffering endured by all who are trampled in the path of war. He created the series of eighty-two etchings, The Disasters of War, between 1810 and 1823. Y no hai Remedio (And There’s Nothing to Be Done) is the nineteenth print in the series; it reflects the hopelessness of war. (Figure 5.7) There is no escape, nor is there justice. Both civilians and soldiers become de-humanized and numb in the endless slaughter, here in the form of a firing squad.

Francisco de Goya y Lucien- tes (1746-1828, Spain) was court painter to King Charles IV from the beginning of his reign in 1789 until Napoleon ousted Charles from his throne in 1808 during the French invasion of Spain. Goya was hired the same year to make a visual re- cord of the bravery of the Spanish people against the onslaught of the French invaders. The impact of what Goya saw, however, changed the direction and tone of the series of prints he made from the unflinching courage of his fellow citizens to despair over the barbarous atrocities committed and merciless suffering endured by all who are trampled in the path of war. He created the series of eighty-two etchings, The Disasters of War, between 1810 and 1823. Y no hai Remedio (And There’s Nothing to Be Done) is the nineteenth print in the series; it reflects the hopelessness of war. (Figure 5.7) There is no escape, nor is there justice. Both civilians and soldiers become de-humanized and numb in the endless slaughter, here in the form of a firing squad.

The print series was not published until 1863, thirty-five years after Goya’s death. There are theories why: the artist was fearful of political repercussions, the scenes were too graphic, or the wounds were too painful for public release in the immediate decades after the war. The artist himself gave no explanation. By the time The Disasters of War series was printed, the French and Spanish governments that had participated in and ruled immediately after the Peninsular War (1808-1814), as it came to be known, had both been superseded. Goya’s documentation of and cry against human self-destruction had no impact at the time of the disasters themselves, but they are still among the most powerful images of political protest ever made.

5.2.5 Scientific Context

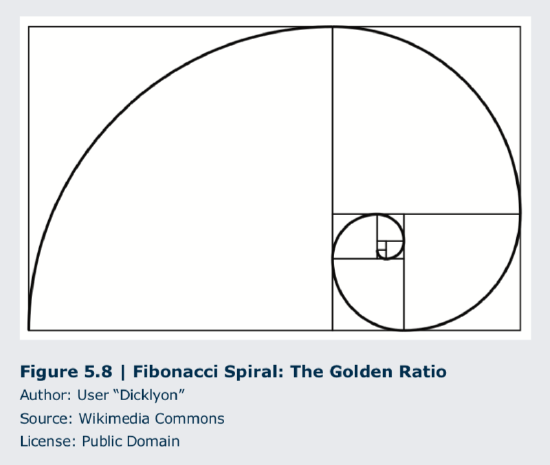

Art and science are inextricably linked. The words “technique” and “technology” both originate from the ancient Greek word tekhne, which means art. For the Greeks, both art and science were the study, analysis, and classification of objects and ideas. Through the study of math and art, they arrived at the golden ratio: when dividing a line in two parts, the longer part divided by the smaller part is also equal to the whole length divided by the longer part. Expressed algebraically, that can be written as a/b = ab/a. The visual representation of the golden ratio, the Greeks determined, results in the most visually pleasing proportions within and of an object or figure. (Figure 5.8)

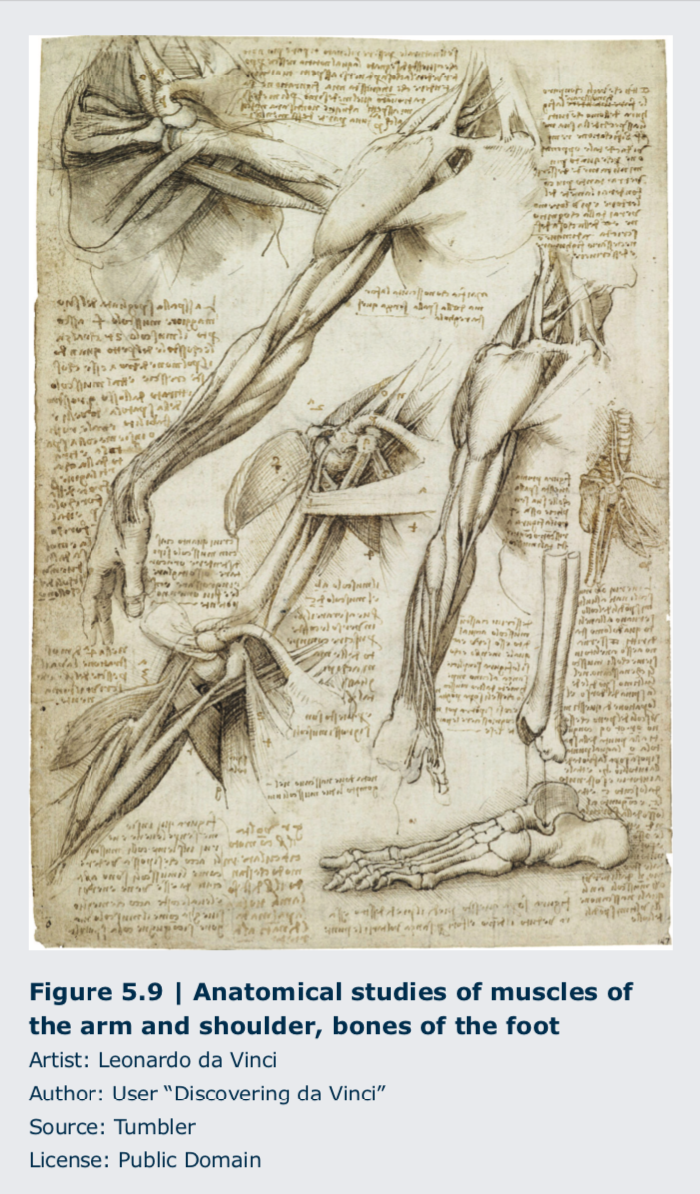

Leonardo da Vinci was fascinated by how things work. The mechanics of nature, machinery, and the human body were all worlds to be explored deeply in order to be understood at their most essential, truthful levels. Although he was interested in human anatomy throughout his career, he spent the last twelve years of his life systematically studying and documenting his findings. He began in the winter of 1507-08 with a series of pen-and-ink drawings that he made of a dissection he carried out on an old man. In the winter of 1510-11, he completed additional dissections, probably working with anatomy professor Marcantonio della Torre at the University of Pavia. (Figure 5.9)

Leonardo intended to include his more than 240 drawings in a treatise on anatomy, but following Marcantonio’s death from the plague in 1512 and political upheaval in the city of Milan where Leonardo lived, his focus shifted and he never completed and published his book. When he died in 1519, his drawings and notes on human anatomy along with approximately 6,500 pages from his other notebooks were dispersed and effectively lost to the world for 400 years. Leonardo’s insights into such areas as the functioning of the heart and growth of a fetus, all completely accurate, had to be laboriously re-discovered by other artists and scientists in the succeeding centuries.

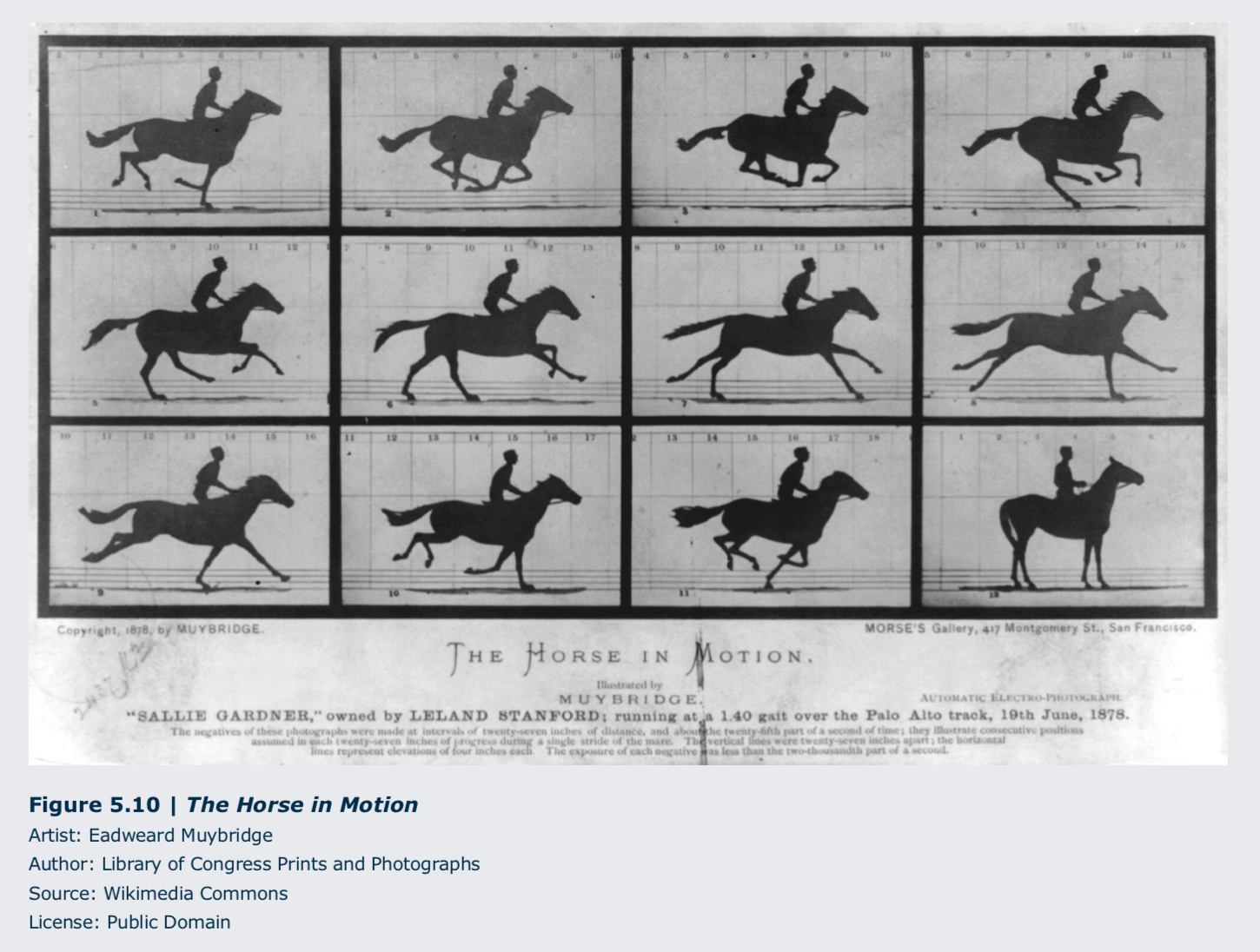

Questions that had long intrigued artists and scientists but could not be answered by observation with the naked eye, such as details about a planetary body in space, a specimen under a microscope, or an animal in motion, were finally being answered in the nineteenth century with the invention of photography. Leland Stanford, head of the Union Pacific Railroad, former governor of California, and racehorse owner, in 1872 accepted the challenge to prove whether all four feet of a horse left the ground when galloping. He hired photographer Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904, England, lived USA) to conduct a study of the sequence of movement that is too rapid to be captured by the human eye. Muybridge experimented with setting up cameras along a track to photograph the horse and rider at evenly spaced intervals. He was soon able to prove that indeed all four hooves are in the air when the horse’s legs are under its body not when the legs are fully extended to the front and rear as many had thought. (Figure 5.10)

While the first set of photographs Muybridge took for Stanford were lost, the industrialist (who with his wife Jane would found Stanford University in 1885) encouraged the photographer to continue his studies. Muybridge published his findings on the galloping horse in Scientific American in 1878. In the aftermath, Muybridge spoke frequently throughout the United States. He was invited to continue his studies at the University of Pennsylvania where his work was valued for the information it would provide in the areas of technology, science, and art. He conducted his photographic experiments there from 1884 to 1887, and the following year he published his book Animal Locomotion, which contained 781 photographic plates of a wide variety of motion studies including men, women, children, horses, lions, bison, ostriches, cranes, and cats.

- “Steamboats.” American Eras. 1997. Encyclopedia.com. (June 22, 2015). http://www.encyclopedia.com/ doc/1G2-2536600971.html

- Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi (Boston: James R. Osgood & Co.), 1883. Accessed from: http://www.gutenberg.org/ files/245/245-h/245-h.htm

- Georgia O’Keeffe, “About myself ” in Georgia O’Keeffe: Exhibition of oils and pastels (New York: An American Place: 1939).