7.5: Modern Indigenous Art (1970-2000)

- Page ID

- 120772

Introduction

The Indigenous Peoples of the world all have distinctive social and cultural groups with ancestral connections to the natural lands and resources they currently reside or where they were dislocated. These resources and locations are intimately part of their ancestral identities, spiritual well-being, financial assets, and cultures. Generally, most groups maintain their leaders and organizations separate from the majority of society and still have their ancestral languages.

Indigenous Peoples own, live on, or use a quarter of the world's surface area and safeguard eighty percent of the world's remaining biodiversity, retaining ancestral knowledge of land management.[1]

Most of the land inhabited by Indigenous Peoples is based on customary ownership, as most governments only recognize a small portion of land as legally held by the Indigenous Peoples. Even in those places acknowledged as officially owned, ownership is insecure and often taken or infringed upon by most governments. The identity of the Indigenous Peoples is defined as descendants of peoples who inhabited the Americas, the Pacific, and some regions of Asia and Africa before European colonization.[2] This section discusses contemporary artists of the Indigenous Peoples found in Oceania, the United States, and Canada.

The region of Oceania is composed of thousands of islands in the Pacific Ocean. It includes the larger landmasses of Australia, New Zealand, and Papua New Guinea, independent islands, and those islands under other countries' oversight. Early Indigenous Peoples were developed as sea-faring cultures, traveling between islands, and establishing permanent communities still existing today. The expansion of European exploration and incursion into other places, the Japanese takeover of many islands, and the ensuing war led to control of the land by outsiders over economics, religion, government, and civil rights. As the largest landmass, Australia has hundreds of indigenous groups composing 2.5 percent of the total population. They are classified as Aboriginal Australians or Aborigines and have cultural and spiritual connections with their local environment. In 1992, the Australian courts recognized Aboriginal rights to land as defined as land owned before Captain Cook arrived, although they inhabited the land for 50,000 years. In New Zealand, the indigenous Māori are almost 15 percent of the population. New Zealand has established a tribunal to oversee Māori land claims and define outcomes. Seven hundred different Indigenous groups are found in Papua New Guinea and are recognized in their constitution with rights under the customary land title. Indigenous Peoples in Australia, New Zealand, and other Oceania areas are still working to codify their rights and treatment under existing governments as conflicts continue between the Indigenous Peoples and governmental and corporate entities.

In the United States, Indigenous Peoples are defined as Native American or American Indian and refers to those whose ancestors lived there before European incursion. American Indian is a specific legal determination by the laws of the United States. Between 2.5 and 6 million Indigenous Peoples live in the United States, with 20 percent residing directly in defined American Indian or Alaskan villages. The largest Indigenous population is in California.[3] The United States government has over 300 treaties with 574 American Indian nations with individuals recognized as citizens of an individual nation by legal definitions. Some states also have different treaties, and many nations remain unrecognized. Each treaty varies; however, they generally include land boundaries, hunting and fishing rights, and protection from domestic and foreign enemies. The treaties supposedly give the nations specific jurisdiction, responsibilities, and economic determinations. However, through the last two centuries, including currently, the United States does not always honor the treaties, and the individual nations have suffered from continued broken promises. In 1887, the Dawes Act broke up tribal lands and divided the land into separate sections. Over ninety million acres of tribal lands were taken and sold to non-native people. The ruling explicitly occurred to destroy Native societies and cultures. Today, the United States government rules require tribal consultation for most issues; however, the government still maintains plenary power, and tribal rights frequently must be handled in the courts. Although the United States government legal system refers to the Indigenous Peoples as Native Americans, they were here long before the country was named 'America.' The term is an example of white exceptionalism and the belief nothing existed on the continent before the Europeans.

Canadian constitution identifies three Indigenous Peoples groups: First Nations (Indians), Inuit, and Métis. Each grouping is based on history, language, culture, and spiritual beliefs. Over 1.5 million people identify with one of the groups. Canada has over 630 First Nation groups representing 50 Nations and languages. The approximately 65,000 Inuit live in 53 communities stretching across the northern parts of Canada and speak Inuktut. Over 587,000 people identify as Métis and live throughout Canada.[4] Much like the United States, the European governments signed treaties with the people living in Canada. Most of the treaties covered hunting and fishing rights, religious practices, trade relations, fur trade, and military requirements. After the Revolutionary War, some treaties granted First Nation groups land; however, as outside immigration grew, land, governmental and religious relationships changed. Treaties were disregarded, the land was taken, and the Indian Act of 1876 imposed greater controls on the Indigenous Peoples. Today, a new methodology, the Inherent Right to Self-Government Policy, provides legal ways for First Nations to negotiate their claims.

Tlingit artist Nicholas Galanin created the following video: his message is universal to the issues and struggles of modern Indigenous populations. Western culture has appropriated symbolic art, sanitized it, and rendered it meaningless to its original meaning. The art of Indigenous people has also been frozen pre-20th century as though modern Indigenous artists did not exist. Current Indigenous artists are trying to bring their cultures back to life, reviving tribal customs using modern concepts, ideas, mediums, and tools. Galanin discusses the intersections of multiple issues as he works on his art. These intersections are common in Oceania, the United States, and Canada.

Oceania

Storytelling has been an essential part of the Aboriginal culture in Australia for thousands of years, and contemporary artists today use the same concepts in their colorful art. Artists incorporate traditional, sacred symbols, relating the practices and laws of past legends. The artwork usually represents aspects of the Dreaming, a concept of supernatural beings and the beginnings of their creation as part of the land and shape of Australia. In the 1970s, Aboriginal groups formed small community art centers in remote locations, beginning contemporary Aboriginal artists' works. Some art centers perform as community centers where painting is a social event, laying the canvas on the ground and painting directly without sketches or preliminary drawings. Artists use traditional materials or mediums found in the geographic areas along with today's commercially available media. Much of the Australian art features circles, wavy lines, or dots usually defined in earth tones. The paintings often reflected ritualistic rites; however, some images were forbidden to be seen and were hidden under the dots and swirls.

In the whole Oceanic region, including Australia and New Zealand, they have a Festival of Pacific Arts every four years, moving the host site each time to different locations. With the participation of artists from over twenty-five countries, the festival is an interchange and sharing of cultural and artistic ideas between the diverse Indigenous populations. The festival includes visual arts, performance arts, and other cultural forms. Participants from many remote island communities can maintain their cultural identities and the importance of retaining their heritage.

Albert Namatjira

Albert Namatjira (1902-1959) (Western Arrernte) was one of Australia's early notable artists, using watercolor to paint the landscapes of Central Australia, his work was different from the traditional artists. Namatjira learned to paint from missionaries, exploiting his natural gift. He highlighted the rugged features of the landscape and the characteristic flora found in the interiors. Namatjira used the sunlight to capture the deep shadows and crevasses or illumination on the trees. He painted the same ochre colors as his ancestors, reflecting the timelessness of the area. Mt. Hermannsburg, James Range, Northern Territory (7.5.1) portrays the dry, barren mountains found in the territory. The scrub trees survive along the riverbank, places for people to live and survive. Namatjira painted scenes recognizable by the outside world, and his artwork was very successful. Even with his money, he could not buy a house or land until his fame forced the government to grant him citizenship as an Australian in 1957. The rest of the Aboriginal population did not receive citizenship for ten more years, unable to own the land where they lived.

Gloria Petyarre

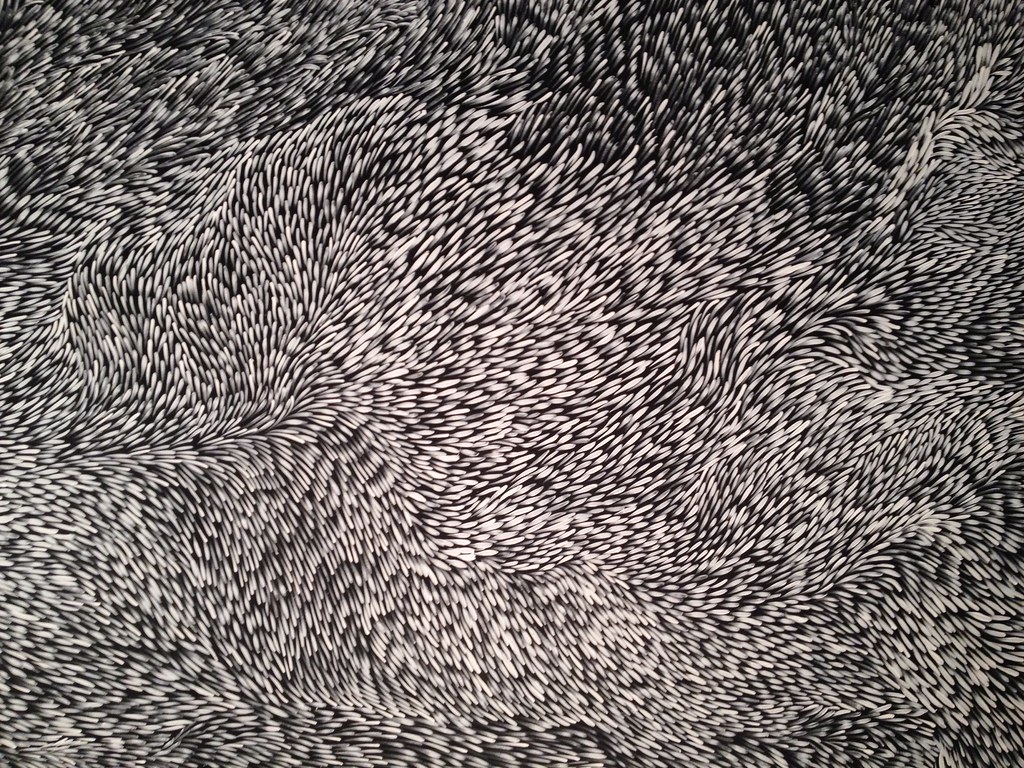

Gloria Petyarre (1942-) (Anmatyerre community) used her traditional leafy and feathery style to paint the very long painting of Leaves (7.5.2). The image projects the feelings of movement, the leaves on a tree, or endlessly falling. Petyarre started as a batik painter and, in the 1980s, started painting on canvas. Also hidden in the painting are references to ceremonies for women and body markings as part of the rituals. She originally started painting with dots before changing to the elongated feathery appearance. "Petyarre grew up learning traditional techniques of reading the landscape to identify foods, medicinal plants, and everything else that was needed to thrive. Sitting under mulga bushes, helping the elder women prepare their seeds for small cakes, she would see the leaves swirl overhead."[5] Many of the women in Petyarre's family are artists whose work is based on the surroundings and rituals of the central desert territory. Their Aboriginal world had existed for tens of thousands of years until pollution by the white cattle ranchers who took the land. Petyarre and the other artists began to paint and demonstrate their knowledge of the historical landscape and the importance of natural substances like leaves.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye

Anooralya (Wild Yam Dreaming) (7.5.3) by Emily Kame Kngwarreye (1910-1996) (Utopia community) represents the dry desert parts of central Australia, a place where outsiders only perceive broad stretches of red dirt. In 1988, Kngwarreye started painting with acrylics and discovered the fluid capabilities of the paint. The churning network of roots from the anooralya or yam plant in the painting demonstrates the vigorous growth in the dry, arid desert. The Aboriginal people understood the land and the resourceful plants able to sustain life. Kngwarreye is considered one of Australia's most important contemporary artists, starting at the age of eighty. She was extremely prolific and produced over 3,000 paintings in her short eight-year career. Her work was stimulated by her position as an Anmatyerre elder and her custodianship of the women's Dreaming sites. When asked to explain her images, she always replied the same: "Whole lot, that's whole lot, Awelye (my Dreaming), arlatyeye (pencil yam), arkerrthe (mountain devil lizard), ntange (grass seed), tingu (Dreamtime pup), ankerre (emu), intekwe (favourite food of emus, a small plant), atnwerle (green bean), and kame (yam seed). That's what I paint, whole lot."[6]

Dorothy Napangardi

Dorothy Napangardi (1956-2013) (Warlpiri speaking) painted Salt on Mina Mina (7.5.4), portraying ancestral women traveling on foot and marking their land with digging sticks. Even today, women gather at the Mina Mina, re-enacting the Dreaming story. The site of the Mina Mina and a stand of large numbers of Eucalyptus trees is where tradition believes the digging sticks came from the ground. Napangardi connected her designs to the traditional designs of Dreaming using interconnected lines and dots. Her works represent the land, the ancestral tracks, and the stories of her female ancestors as they moved through the landscape.

Paddy Nyunkuny Bedford

Although Paddy Nyunkuny Bedford (1922-2007) (Gija language group) was born in 1922, he did not start painting until 1998, when other artists in his area formed an art center. Bedford derived his name from Bedford Downs, where he was born, and his first name from the person who ran the cattle station. As with many other young Aboriginal men, Bedford worked on a cattle station, hard, dirty work. The Europeans took vast swaths of land controlled Australia and established cattle ranches throughout the country. In 1969, the government enacted equal pay legislation for the Aboriginals who worked alongside the white workers. Most of the Aboriginal people, who had been paid with rations instead of money, were fired because of the law, and the cattle station owners refused to give all the workers equal pay. Before Bedford started painting as an artist, he was involved with ceremonial painting. As an artist, he created loose depictions of the surrounding landscape. Yoowageny-Mud Springs (7.5.5) represents the region around water, creating events of the ancestral Dreaming stories and history of the area. Bedford used black and white with smaller amounts of color, a more minimal interpretation than other artists. Today, he is one of Australia's most sought-after artists.

John Mawurndjul

John Mawurndjul (1951-) (Kuninjku people) follows a tradition of painting from generations of people before him, telling stories of the Kuninjku culture and the surrounding land. He said, "The old ways of doing things have changed into the new ways. The new generation does things differently. But me, I have two ways. I am the old and the new."[7] Mawurndjul is considered a master of rarrk, the finely painted cross-hatching, based on the tradition of his ancestors. His images include sacred places and the animals or spirits inhabiting the sites, especially the rainbow serpents or ngalyod. Mawurndjul used the materials he found, including white clay, yellow and red ochres, and the bark of eucalyptus trees. He used the sedge plant to make single-strand brushes for the fine cross-hatching. Ngalyod (Female Rainbow Serpent) (7.5.6) is the image of the rainbow serpent, which rises and pulls people down into the ground, turning them into bones. The white clay of the earth is from the serpent's feces. During the wet season, she appears in the sky as a rainbow, making rain. The rainbow serpent is like a crocodile, dangerous, killing people and animals. Mawurndjul used rarrk or polychrome cross-hatching. The lines, dots, and circles form the snake's body that lies waiting, representing the Dreaming being, Ngalyod.

Vincent Namatjira

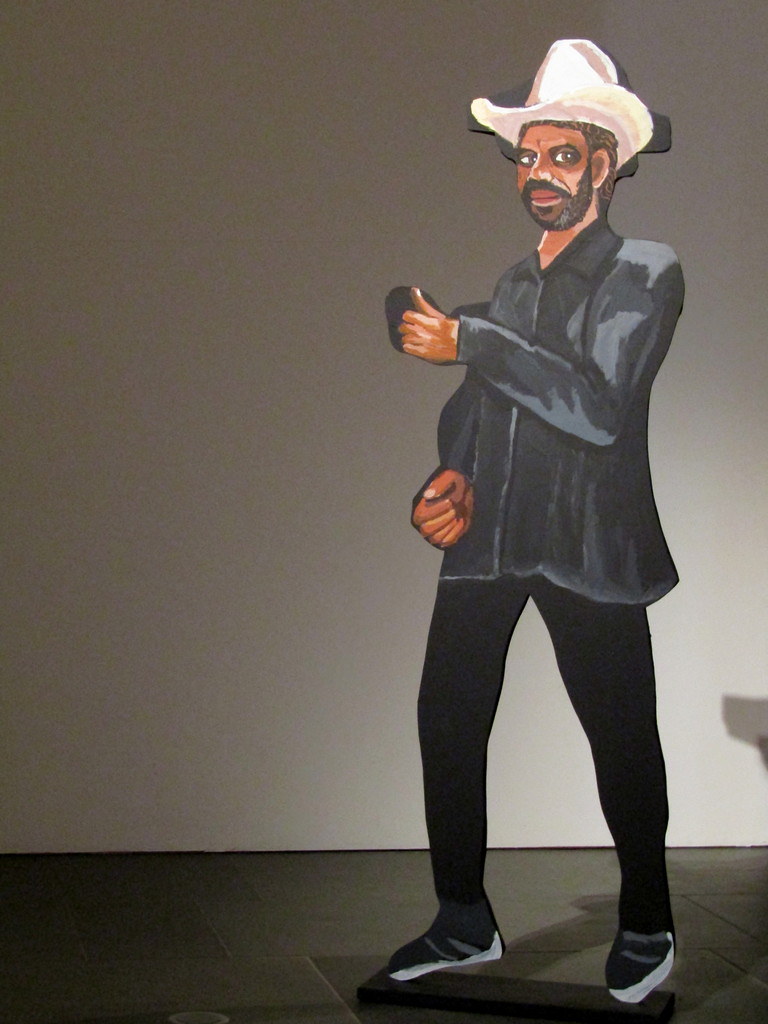

Vincent Namatjira (1983-) (Western Arrernte background), born in 1983, represents the newer generation of remote Aboriginal Australian artists. His great-grandfather was Albert Namatjira, who was famous for his watercolors. Vincent Namatjira's artwork is often called caricatures, sometimes considered by others as "outsider art." His work is based on historical colonial narratives, critiquing the struggles and controls of Australia's relationships with Europe, especially "the Empire" or England. Namatjira focuses on the connections between wealth and power.

Close Contact (7.5.7, 7.5.8) is double-sided on plywood instead of his usual canvas. On one side, there is an image of Captain Cook, who led the British invasion of Australia and was called the colonizer. On the other side is the Indigenous Australian, the colonized. The double-sided image defines the past and the present, like Namatjira's other paintings of political and historical figures from a modern Indigenous perspective. He used an ordinary jigsaw to cut the plywood and applied his trademark bold paint.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Close Contact side 2 (acrylic on plywood) by Pat M2007, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Close Contact side 2 (acrylic on plywood) by Pat M2007, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0Kaylene Whiskey

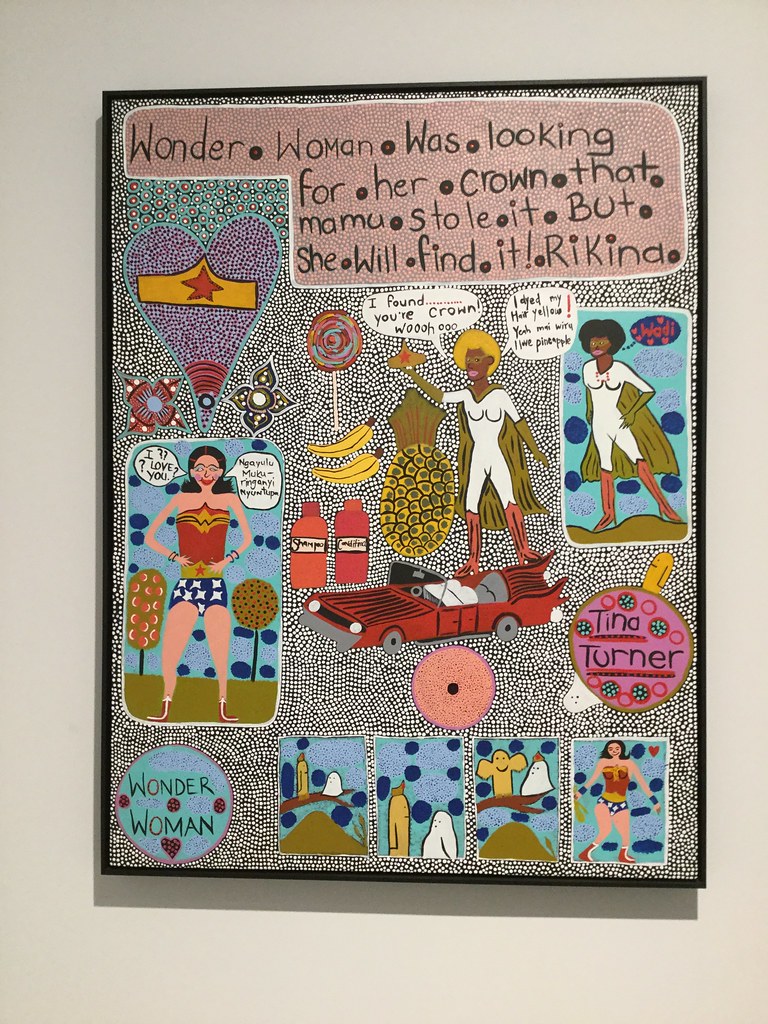

Kaylene Whiskey (1976) (Pitjantjatjara), a modern Aboriginal artist, creates her art in one of the remote communities in South Australia. She was the granddaughter of an earlier artist whom she used to watch paint in the art center. As Whiskey developed her style, she used bright colors while listening to American pop singers who inspired her work. She incorporated their images into her paintings. Whiskey stated she liked to have fun and painted people in interesting outfits combining contemporary life and her remote community. Rikina Kungka Kutju (One Really Cool Lady) (7.5.9) demonstrates her comic book style of painting illustrating popular western culture and her own Indulkana community with evident feminist undertones.

Michel Tuffery

Michel Tuffery (1966-) (New Zealand) was born in New Zealand; his mother was Samoan, and his father was Tahitian; his work is based on his Polynesian legacy. Tuffery creates art from his heritage, the results of colonialism, and the polluted state of the environment. He is part of the new generation producing culturally based art using Western mediums. Tuffery's sculpture, Pisupo Lua Afe (7.5.10), was created from hundreds of corned beef tins he flattened and riveted together to shape a life-sized bull. The first canned food brought to the Pacific Islands by Europeans was pea soup called pisupo in Samoan. Today, pisupo is a generic word for any canned food, including corned beef. Canned corned beef is very popular and exceptionally high in salt and fat, contributing to the high rate of heart disease and diabetes in the Oceanic population, who previously ate local seafood and vegetables. Tuffery's sculpture reflects the unhealthy aspects of canned foods, the environmental damage of littered cans, and the negative impact of the imported cattle growing operations.

.jpg?revision=1)

Nga Kina (7.5.11) is a tribute to the history of the New Zealand waterfront by the Kumutoto river. The giant shells are made of concrete and fiberglass against the river weighing five to seven tons. At low tide, the entire sculpture is visible, and only the tops of the shells are seen at high tide. The sculpture is a tribute to the Maori settlement and is based on the midden or shell mounds the local Maori made when they harvested the natural shell lifeforms from the local waters.

.jpg?revision=1)

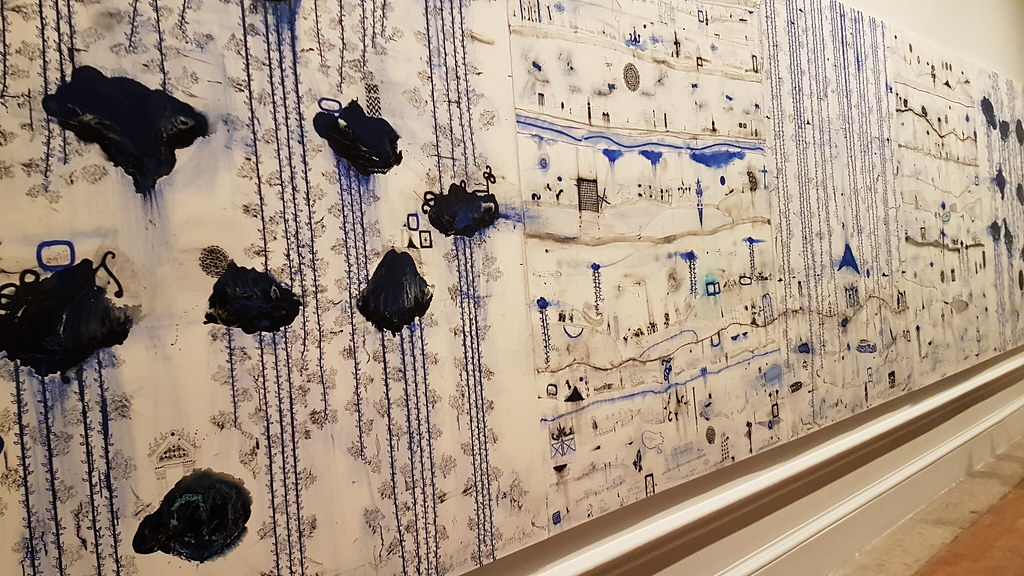

John Pule

John Pule (1962) (Island of Niue) was from the tiny island of Niue, 2,400 kilometers from New Zealand, a self-governing state associated with New Zealand. Polynesians from other islands initially settled on the island; European contact first occurred when Captain Cook tried to land. Pule's family moved to New Zealand when he was two, where he grew up, returning to the island for visits. Pule's artwork is heavily influenced by colonialism while using mediums from both worlds, including canvas and bark cloth for painting. Kehe tau hauaga foou (To all new arrivals) (7.5.12) ambitious work covers the conflicts of human relationships from his perspective of people from the region. The painting is like a massive painting of Pacific ideas, contrasting colonialism, pollution, global warming, religion, and nuclear testing. Pule incorporated multiple world venues in the painting as though they were located together. He looked at the world as a mix of the mythic past integrated into the contemporary views of conflict.

United States

The Indigenous Peoples living in the United States are composed of multiple nations, tribes, and clans, and their artwork reflects the diversity of the people. In the past, indigenous art was classified as a craft because most surviving arts included clothing, baskets, or pottery created by women and anonymous. Today's modern female artists still maintain the connection with the past, their artwork recognized. The contemporary Native artists come from the hundreds of recognized tribes and nations and may work with materials of the past or modern materials. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Native children were taken from their homes and placed in boarding schools throughout the United States to assimilate into the white culture. Students' names were changed, their native dress was replaced, and they were forbidden to speak their native languages. The art and culture of the generations are lost. Many of the schools were open for over one hundred years, only closing in the late 1980s. Today, the scope of Native people's art has changed; even museums are holding exhibits among "traditional" art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York stated: "The art of the indigenous peoples of North America have not historically been prioritized in these spaces. The longstanding curatorial practice of designating arts as "primitive" or as "ethnographic," or as "nonwestern" has limited our capacity to see a broader and more shared humanity…"[8] Modern and contemporary Indigenous artists work in the same range of artistic medium as other artists, and the omission of Indigenous art brings an incomplete picture of today's art.

Joe Feddersen

Joe Feddersen (1953) (Okanagan) is a photographer, sculptor, and painter who frequently bases his art on the geometric patterns found in the natural landscape and heritage. With a BFA and MFA degrees, he was a college professor before finally devoting himself to art. Feddersen stated: "My work investigates sign and cultural identity. This inquiry merges basic elements of basket designs from my ancestral home, the inland Plateau region of the Columbia Basin, with urban imagery to speak to perceptions of land."[9] Feddersen's work is non-representational, made from lines, shapes, colors, and texture, or viewed as symbolic of his heritage. His robust geometric patterns portray the relationship between his urban environment and the indigenous iconography of his culture.

Okanagan V (7.5.13) is a ninety-panel installation made with relief prints on paper and then mounted on board. The different panels are made with geometric patterns and highly contrasting colors. Each panel was assembled to form an overall geometric format. Feddersen is also a well-known basket maker after studying Colville's traditional basket patterns. The designs on the baskets were made to tell stories as well as the practical use of storage. Feddersen started making baskets and used them to teach others about their culture. His interest in basket making expanded to glass, and he learned glass making. Feddersen creates patterns based on the images he sees in baskets and translates them into glass.

Fish Trap II (7.5.14) is based on the woven fish traps the Indigenous people made to catch the abundant fish in the rivers. The traps were loosely woven to let the water flow; the purple glass is marked with the woven lines.

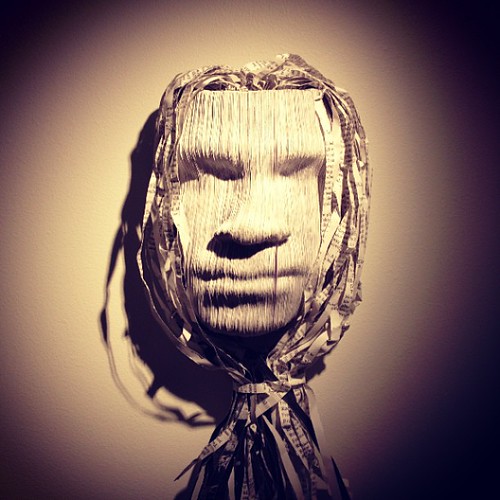

Nicholas Galanin

Nicholas Galanin (1979) (Tlingit & Aleut) from Sitka, Alaska, learned art by working with his father to make jewelry, even earning a BFA in jewelry design. Galanin expanded his art portfolio after completing this MFA in visual arts at the university in New Zealand and became a multi-disciplinary artist. He also focused on the concepts of identity relationships between the Native communities and non-Native. One of Galanin's first series was based on sculptures using books. He used anthropological texts from the 19th century and carved them by hand and laser into faces. In Medicine Man (7.5.15), Galanin used over 1300 pages, some bound and others cut. He wanted to challenge all the words and texts defining a contemporary indigenous man he found when reading. Galanin found most of the information about his culture was related through oral recitations. Books were institutionalized, the writings about culture from people outside the culture.

Things Are Looking Native, Native's Looking Whiter (7.5.16) is a photomontage Galanin created using the image from the Star Wars movie. In the film, Princess Leia wears a distinctive hairstyle. On one side of the photomontage, a Hopi-Tewa woman wears the traditional "squash blossom" hairstyle, and on the other side is the Star Wars princess with the same style. Galanin's work is a commentary on the Western media's cultural use of visual images from non-Western cultures, decontextualizing and removing crucial cultural context. He believed the appropriation of Indigenous culture was based on the past and had no existence in the current cultural presence.

Nora Naranjo-Morse

Nora Naranjo-Morse (1953-) (Santa Clara Pueblo) was the youngest daughter of a well-known potter. She had eight siblings, and their mother gave each of them clay to play with when she was working, the inspiration for Naranjo-Morse to continue the tradition. She is also known for her writings as a poet. Although there isn't any word for an artist in her Tewa language, they did have a concept of the artful life. Naranjo-Morse believed her work with clay and writing poetry gave her creative expression. She used the traditional idea of Pueblo figurative statues created in a contemporary method. The female figure stands slightly in front of the male, acknowledging the role of women, a previously matrilineal government. The concept of leading females was changed when the society modeled Euro-American governments, a patrilineal model. Many tribal ruling structures reorganized when Congress enacted the Indian Reorganization Act in the 1940s, changing tribal life forever. The Khwee-seng (7.5.17) bronze sculptures are abstracted; the female has a turquoise necklace while the male wears a zig-zag pattern.

Always Becoming (7.5.18, 7.5.19) is installed outside the National Museum of the American Indian. Naranjo-Morse made each statue from clay, stone, pottery shards, agave fiber, sand, wood, bamboo, and dirt, each sculpture changing and eroding over time from the weather. She stated in an interview, "I'm hoping the Native community sees themselves in this. [I want them to see themselves in a way] that's always changing that's always relating to the environment, and always adapting and transforming. And in that process being empowered."[10] Naranjo-Morse incorporated smaller pieces of shards, stones, and other materials, and part of the structures was based on small pieces eroding and falling to the ground, leaving them to become part of the earth again. In her book, Mud Woman, Naranjo-Morse wrote about the Pueblo people's long-term relationship with clay. "Veins of colored earth run along the hillsides of New Mexico, covering remote trails with golden flecks of mica. Channels of brown and scarlet mud wash across the valleys, dipping and climbing with the sprawling landscape. Intricately woven patterns of clay fan out under the topsoil, carrying the life of pottery to the Pueblo people."[11]

Roxanne Swentzell

Roxanne Swentzell (1962-) (Santa Clara Pueblo) was also from a family of artists, her aunt Nora Naranjo-Morse. She learned traditional pottery making from her mother, other family members, and local potters, playing with clay scraps as a child and turning them into little figures. Her artwork is based on her childhood memories and her own experiences to focus on female issues, politics, family, and identity. Swentzell learned how to make small coil pots as a child, the method she uses today to create her figures. However, she does not dig and process her clay. Instead, Swentzell uses commercially made clay. To construct a figure, Swentzell manipulates the clay into thick coils for the walls of her figures, then smoothing the sides. This process makes the statues hollow, except for the fingers and toes. She generally paints the finished clay figure.

Mud Woman Rolls On (7.5.20) is an immense sculpture. The figure has straw wattles (long tubes of straw) for the basic form, then covered with clay. The straw wattles are flexible and able to be shaped. Mud Woman has four children, each one holding the other. Swentzell used mud from different locations for the color of the figures. The mother's hair was composed of various grasses dyed with natural colors to make the hair strands. Swentzell wanted to celebrate the female body along with the nurturing relationship of mothers and the earth. She wrote, "The Mother holds the largest child, who's holding the next child, who's holding the next, and so on. I loved the perspective of understanding that we all come from the Earth, generation after generation; an endless family of life passing on the seed."[12]

The figure of Kosha is similar to the image of a clown who appears in ceremonial events, teaching others through their actions. In the Pueblo story of creation, the Kosha emerged first from the underworld. The statue, Kosha Appreciating Anything (7.5.21), depicts the clown gazing at his hands as though something important is happening, a reminder to think before making choices. The stripes on the Kosha symbolize balance, another of Kosha's lessons. The statue is hollow and made with coils, smoothed, and then fired.

Allan Houser

Allan Houser (1914-1994) (Chiricahua Apache) from Oklahoma was the first person in the family from his Apache tribe to be born outside of captivity since the U.S. government imprisoned them. His father, a cousin of Geronimo, was part of the Chiricahua Apache tribe imprisoned after the defeat of Chief Geronimo by the U.S. government troops. The Apache children were taken from their parents and placed in a Pennsylvania boarding school to "have the Indian removed." Almost one-third of the children died. After 27 years of imprisonment, the remaining people of the tribe were freed from prison and sent to Oklahoma, where they were placed in different villages and where Houser was born. Houser was born in 1914 and is one of the older people in this section's writings. His early career was very successful in art and education; however, when Houser retired in 1975, he started the most significant prolific part of his career. During this time, until he died in 1994, he combined the concepts of Native subject matter and the general sleekness of Modernism, producing some of his most memorable works. In two decades, Houser created almost 1,000 Native people sculptures. Made of stone, wood, or bronze, the statues displaying compassion and dignity.

Homeward Bound (7.5.22) depicts a young Navajo woman holding a lamb as she and the dog take the sheep across the bridge. Her job is to take the sheep out to the pastures and bring them safely back at night. Sheep were essential to the life of the community; their wool was used for weaving. The woman is clad in traditional dress, including the Navajo hair bun and earrings.

Reflections (7.5.23) is a sculpture made with thin bronze plates, cut into shape, and then hammered. The last step is to weld the parts together to form the expressive female figure. The work is one of Houser's most abstract sculptures, rendering the illusion of the woman whose stress or feelings remain unknown. Houser was close to his mother, and he used the concept of mother and child throughout his work.

Singing Heart (7.5.24) was made of stone and can also be seen in bronze. In most of his statues of mother and child, the mother is proportioned much larger than the child, who is almost joined as one, a protective position. Like his other mother and child figures, this one is organic, round, appearing soft yet robust. He used different types of stone, and like the others, this image has contrasting smooth and rough textures. Houser felt his images told the story of the Apache people, their relationship to Mother Earth, and their pride and spirit.

Truman Lowe

Truman Lowe (1944-) (Ho-Chunk) grew up on the Ho-Chunk reservation in Wisconsin, speaking Winnebago until he went to the mission school. Without art supplies, Lowe used rocks from the river to draw, even grinding them up for pigment. When he was in high school, he spent time outside drawing, especially exploring how snow looks on the branches of trees and how to translate that into a drawing. His family made baskets and did beadwork to sell to tourists for additional income, items used as part of everyday life, sold as tourist curios. While he was at the university, he began to learn the concept of art and art as a profession versus the common idea his parent's work was considered crafts and not valued. Throughout Lowe's university period, while he received a BFA and MFA, he worked with plastics and synthetic materials. The materials were popular at the time, and he experimented with various possibilities. However, after Lowe started teaching in Kansas, he reflected on the past, realizing his roots were in the woodlands and natural materials. Lowe used the traditions learned from his parents and blended them with modern ideas, always talking about how wood is alive. When Lowe was teaching, he brought his knowledge of nature and its relationship to Native cultures into the classes. Lowe was also a curator for the National Museum of the American Indian and brought his ideas to establish the concepts of contemporary Native art.

Many of Lowe's artwork used willow saplings as the material, collecting the saplings in the summer and peeling the bark off before storing them. Willow branches are flexible and strong, and Lowe was able to manipulate and bend them without breaking. During a visit to an archaeology site near the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, Lowe investigated the sand pedestals holding remains of the buried people. His artwork, Wah-Du-Sheh (7.5.25), means bundle. Bundles were special and held specific objects or medicine. The art portrays an illusion of humans who respect special objects, the spirit transcending the ordinary.

Lowe's love of the woodlands is reflected in all his work. He understood the land and water relationships and spent much of his time canoeing the local rivers. His work, Water Whispers (7.5.26), uses flowing glass to give the appearance of a waterfall, reflecting the importance of flowing water and the tenuousness of the environment. Lowe used stainless steel rods to hold the rippling glass in place.

Wendy Red Star

Wendy Red Star (1981-) (Apsáalooke-Crow) grew up on the Crow Reservation, uncomfortable with her "otherness" when she left the reservation until she learned to deal with it through her artwork. In college, she focused on sculpture, including painting, beadwork, fiber art, photography, even performance art. Red Star uses multiple media, frequently incorporating fiber work and photography to depict issues of Native cultures through disparate layers of images. Although Red Star combines stereotypical and authentic imageries in her work, she wanted to refer to and integrate modern and past, humanizing Native people as still relevant and authentic today. Red Star noted:

"It is critical to preserve and pass along culture, heritage, and shared values while also providing future generations with a sense of identity, solidarity, and empowerment."[13]

Red Star believed the traditional photographs of Crow women were flat and colorless. She used herself and her daughter as models and took photographic images dressed in fashionable Apsáalooke (Crow) clothing. In Apsáalooke Feminist #2 (7.5.27), bright blue blankets cover their laps, one with bold flowers, the other fringed. They are sitting on a modern yet plain white couch, a background for Red Star's decorative blankets folded and laid on the couch. She and her daughter wear clothing to honor the maker and wearer, the beaded belt, the elk tooth dress, and moccasins. Red Star even collaged the background and foreground into the pictures to add dimension, color, and interest. Red Star also named her photograph to connect gender and racial equality. She explained, "As a brown person, as a brown artist, your work is political."[14]

Red Star also supports the community, helping others to expand their knowledge of ancestral and present culture. Red Star helped high school girls make traditional shawls with modern materials as part of the shawls she makes. Each shawl in her display (7.5.28) has different symbols representing aspects of their culture with ribbons resembling fringe.

Teri Greeves

Teri Greeves (1970-) (Kiowa) was born on the Wind River Reservation, where her mother had a trading post. Greeves was exposed to multiple tribes' beadwork and methods as she heard her mother talking to customers. She learned beadwork skills from her mother and other beadwork masters who sold their work at the trading post. Although Greeves received her degree in American Studies, she continued her mastery of beads and focused on her art. She learned multiple methods to apply the beads, including a lane stitch, like quillwork with the design built from multiple rows. Greeves uses a loom for bracelets, and if she creates a large image on deer hide, she attaches the hide to a board. Asked about her work, Greeves stated, "I am a beadworker. I've been beading since I was about 8 years old. I am compelled to do it. I have no choice in the matter. I must express myself and my experience as a 21st Century Kiowa and I do it, like all those unknown artists before me, through beadwork. And though my medium may be considered 'craft' or 'traditional,' my stories are from the same source as the voice running through that first Kiowa beadworker's needles. It is the voice of my grandmothers."

When she was only thirteen, Greeves saw a set of beaded tennis shoes one of the Lakota artists brought for her mother to sell at the trading post, and Greeves loved them. When she was in college, her mother asked her to make a pair of beaded tennis shoes and has created them ever since that call. Instead of beading moccasins, Greeves uses tennis shoes to tell her Kiowa and cultural stories in a new way. She makes an original drawing before applying the basic lines on the shoes, then stitches on the beads. She generally uses both a lane stitch and two-needle applique to apply the beads. Kiowa Aw-Day (7.5.29) illustrates the children celebrating their day, the beaded young boy in his yellow buckskins. The images of the children contrast against the bright red shoe color.

Greeves Great Lakes Girls (7.5.30) are beaded on high-heeled tennis shoes, the images inspired by the floral designs from the Great Lakes tribes. Although the dancers are beaded in traditional clothing, the images appear modern.[15]

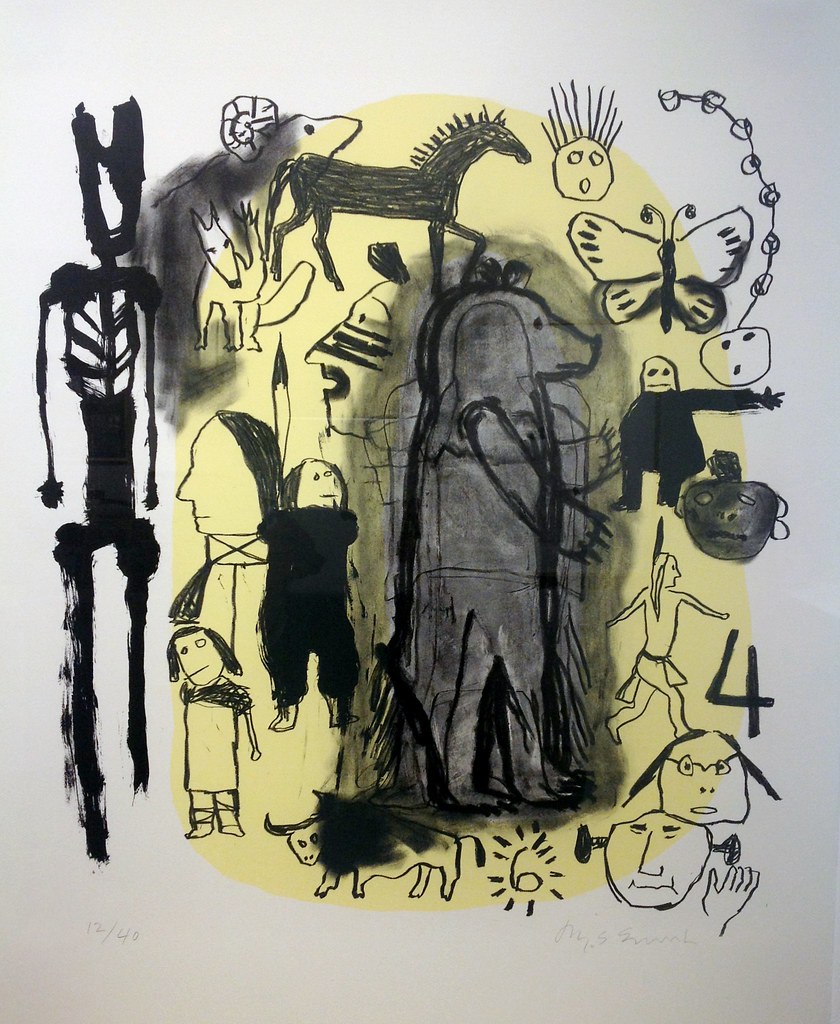

Jaune Quick-to-see Smith

Jaune Quick-to-see Smith (1940-) (Salish and Kootenai) was from a small town on a reservation in Montana. Her childhood was one of poverty, moving from place to place and working summers as a migrant worker on the farms. Even as a child, Smith knew she wanted to draw, using sticks to create images in the dirt. When she started school, she remembered the first time she had crayons and paints, saying: "I loved the smell of them. It was a real awakening. I made a painting of children dancing around Mount Rainier. My teacher raved about it. Then with Valentine's Day approaching, I painted red hearts all over the sky. …I see it as my first abstract painting."[16] Throughout her education, including her eventual master's in art degree, Smith moved between Native and the non-Native cultures, producing art bridging the social and political issues between diverse cultures. Smith has always produced complex paintings and lithographs, highly textured images using mixed media. She also combines the abstract and representational in her work, portraying the myths of ancestors integrated with the issues facing Native Americans in the current world. Smith's work addresses the devastation of the environment and governmental oppression. Smith moved to New Mexico, a place she found deeply personal, like the artist Georgia O'Keeffe. "But while O'Keeffe focused her attention on the timeless uninhabited landscapes of her adopted home, Smith's 'inhabited landscapes' express the human conflicts marked on the land."[17]

Smith's work was always based on her ancestral background, integrating today's concepts. Sticky Mouth (7.5.31), the translated Blackfeet word for bear, is titled to reflect one of the bear's favorite foods - honey. The bear in Native mythology is a messenger at times and sometimes considered an ancestral figure. Smith surrounded the bear with different images of Native people. A coyote is also depicted. Smith identified herself with the coyote who delivers warnings about the danger and bad behavior results, part of her role moving through and representing different cultural activities. The map of the United States is a frequent background Smith used, embedding the cultural and environmental issues she addressed.

State Names (7.5.32) defines how occupied land was taken by invading Europeans. Smith used paint dripping and collaged layers for the painting, leaving only the names visible based on indigenous sources, highlighting the historical injustices. Many of the names come from Native American words; Wyoming, a Delaware Indian word for "mountains and valleys alternating," or Kansas, a Sioux name for "people of the south wind." In the image of State Names, Smith displays her anger for land division without any regard for tribal lands. She stated, "We are the original owners of this country. Our land was stolen from us by Euro-American invaders…I can't say strongly enough that my maps are about stolen lands, our very heritage, our cultures, our worldview, our being…Every map is a political map and tells a story-that we are alive everywhere across this nation…"[18]

Rick Bartow

Rick Bartow (1946-2016) (Wiyot) was born in Oregon; his father's Wiyot Tribe was indigenous to California in Humboldt County. While the family lived in Oregon, they established a close relationship with the local Siletz Indian community. Bartow was interested in both art and music from an early age. Although no one in his family was artistic, he drew all the time. Bartow, drafted after college, was sent to Vietnam during the war, and after recovering from PTSD, alcoholism, and drug use, he started full-time on this art. His early work often reflected on his dark problems at the time. Bartow's work is more mystical, and he frequently portrayed transformational figures or humans becoming animals or birds. His art was expansive, and he made pastel and mixed media works, wood sculptures, etchings, and ceramics and continued with music. Bartow developed different approaches; his pastels were abstracted, acrylics were bold, wood sculptures were based on the innate texture of the material, and ceramics became fluid. Bartow's work can be radical and unconventional, and even his family disapproved. "I once did a picture of my old Indian uncle, who lived next door to me, and when I showed it to him, he said, 'Put it in the barn; it will keep the rats out.' Sometime later I went to an exhibit of Pacific art, and I was just knocked out by these African pieces that had nails in them. When I came home, the first piece of wood that I came across that had nails it in was an old fence post, so I started yanking up fence posts from my uncle's pasture and cutting them up. I was making dogs and people, and I started pounding more nails in. My uncle just thought it was crazy. He could barely contain himself when he saw those; they made him incensed. Then, when the first one sold for $1,500 at the gallery, he started bringing me fence posts. I knew then that I was amongst the counted."[19]

When Bartow was contacted to create a sculpture for the entrance to the American Indian Museum, he did not want to make a totem pole because they were not part of his Wiyot Tribe culture, and the totem pole has specific meanings and iconography. He agreed to make a pair of sculptures entitled, We Were Always Here (7.5.33) and involved the community in carving the undulating peaks and valleys. At the top, Bartow added native icons from the Northwestern region, including the raven, bear, salmon, and eagle. Each of the figures had a special meaning to Native cultures and Bartow himself. The poles were carved from 1000-year-old red cedar planks, the symbolic images at the top causing people to look up and see remembrance, hope, and survival in the face of adversities.

The sculpture From the Mad River to the Little Salmon River or The Responsibility of Raising a Child (7.5.34) depicts a baby-actually Bartow's daughter looking out of her Plateau basket. The basket is perilously perched on the back of Coyote, the trickster. The eagle, a salmon and raven, and other animals surround the child, guarding it. Different faces and animals from the Oregon coast also help to protect the child. The moon mask carved on the eagle's tail represents women, while the sun mark on the eagle's wing symbolizes men. The sculpture was personal to Bartow, and he thought of it as about "pride of place, love, lost and found, [and' survival," believing, "the trickster Coyote can create chaos and harm. Consequently, parents may need help, especially from the love and support of community members, in raising a child."[20]

Deer Dancer for Hyacinth (7.5.35) is one of Bartow's most haunting works. After the Vietnam War, when he fought addiction, he created his darkest compositions. In this image, the misshapen male figure appears to be transforming as his head seems to be spouting antlers. The use of pastels and charcoal gives the portrait an intense feeling, almost mystical. The body appears to be fading away as the darker face provides a slight hint of emotions.

Canada

Canada has a vast and varied landscape, stretching from ocean to ocean and into the frozen lands of the north. Most of the inhabitants are found near the rivers and seas and along the southern border. First Nation people lived throughout the regions before the incursions of the Europeans, looking for new trade routes, land, fur, religious conversions, or other riches. Art was created before the European invasions by people, made with local materials based on historical customs. With the large numbers of Europeans and the total disruption of the Indigenous lifestyles, art became a way to make money from the tourist trade and those who thought of themselves as collectors of "native arts and crafts." By the early 1900s, most First Nations peoples were forced or migrated from historical lands, losing natural histories, cultures, and arts.

Norval Morrisseau is frequently credited with bringing back the cultural past through art. His vision and determination in the 1960s happened when he brought his unique artwork to a gallery, and started changing the concept of Native art. At this time, enforced assimilation was the Canadian practice, and First Nation peoples had just acquired the right to vote. Their artistic expressions were still thought of as artifacts. A few other artists formed the Indian Group of Seven in the 1970s, creating art based on their cultural traditions, portrayed in modern styles, and expanding the platform of opportunities for Indigenous artists. Today, contemporary First Nation, Metis, and Inuit artists have established themselves. They use ancestral connections, continuing social conditions, and colonial histories to inform their artwork created in contemporary practices.

Norval Morrisseau

Norval Morrisseau (1932-2007) (Bingwi Neyaashi Anishinaabek) was born on an Ojibwe reserve in Ontario. Raised by his grandparents, a common Anishinaabe tradition, he learned the legends of the Ojibwe from his shaman grandfather and the religious elements of Catholicism from his grandmother. Sent to a residential school, the Canadian government's system established in the 1880s, his culture and language was forbidden. Morrisseau wanted to draw and spent time alone; the school sent him home because he did not fit in. When he married in the 1950s, Morrisseau devoted more of his time to art, working in a mine to add income and meeting a European doctor who encouraged Morrisseau's art. The doctor bought him supplies and encouraged him as a professional artist. Morrisseau started selling his art and gained the support of others. In 1962, he exhibited his art in a gallery in Toronto, the first time a contemporary gallery displayed modern Indigenous art. He was criticized, and his art was criticized; however, others noticed, and the concept of quality, successful contemporary Indigenous art started to grow. Morrisseau had battled with alcoholism since he was a young teen, and in 1973 when he was arrested and jailed for six months, he had time to paint some of his most successful work. When he was released, two documentary films were made about him reflecting the assimilationist program, a plan "which aimed to extinguish Indigenous cultural distinctiveness." [21] However, the films also raised the interest in Morrisseau's artwork and started the beginning of public acceptance of Indigenous art.

Morrisseau believed his paintings had power in the sacred images, like an amulet. He sketched his basic scenes quickly and did not use color in any formula or relationship, only adding color where he wanted. In Androgyny (7.5.36), the snake symbolized how Morrisseau connected to the spiritual world as the snake reached upwards from the underworld. The dome of the cosmic universe covers the outstretched wings of the spirit Thunderbird. Other spirit beings are added as the life force of everything alive, animals, turtles, fish, frogs, birds, butterflies, and humanity of men, women, and children, all children of Mother Earth. Morrisseau used these familiar images in other paintings. The painting was installed in a remote building from 1983 until 2006 when it was shown in the National Gallery of Canada exhibition. Today, Androgyny is recognized as one of Canada's most significant pieces of art.

All Morrisseau's paintings were focused on Anishinaabe art, using heavy black lines to divide spaces for the dramatic clashing colors. He usually did not mix colors, only applied them directly from the tube with a brush or his fingers. He always used a balanced composition, a central image, or an asymmetrical formation for two images. A Separate Reality (7.5.37) depicts the spiritual powers of humans, animals, plants, and the different celestial bodies all shared in the general universe. The shape of the dome encloses the four figures representing the directions of north, south, east, and west: the dome is also the shape of the sky. The dome shape is used in some homes or ritual sites. Outside of the dome are the spirits, animals, and people who are part of the universe. Morrisseau spent hours in his childhood learning about the guiding powers in life and the universe, and many of his works incorporate the concepts from his shaman grandfather.

Figure \(\PageIndex{37}\): A Separate Reality (1984, acrylic on canvas, 3 x 6.4 meters) by Vlastula, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Figure \(\PageIndex{37}\): A Separate Reality (1984, acrylic on canvas, 3 x 6.4 meters) by Vlastula, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0Daphne Odjig

Daphne Odjig (1919-2016) (Potawatomi & Odawa) painted before a contemporary Native art movement existed. Odjig is now thought of as the grandmother of Canadian Native art. Born on an Indian Reserve, her father was a descendent of the well-known Potawatomi Chief Black Partridge. Suffering from rheumatic fever when Odjig was a young girl, her grandfather, a stone carver, stayed with her, encouraging her artwork. She started creating art using multiple mediums while working in different jobs to support herself. Because of the racial discrimination Odjig encountered, she anglicized her name and suppressed her Indigenous identity. While attending a dance ceremony, the beat of the drums made Odjig realize her heritage, and she redirected her work to depict her traditions and history. In 1963, Odjig was recognized as a formal artist based on her pen and ink drawings to portray and preserve the Cree people and their traditional lifestyle. She started her store on the way to her success. In 1973, Odjig, Norval Morrisseau, and Alex Janvier started the Professional Native Indian Artist Association, commonly known as the Indian Group of Seven. Although the group did not last very long, they successfully broke through barriers as a united set of artists. Odjig stated, "If my work as an artist has somehow helped to open doors between our people and the non-native community, then I am glad. I am even more deeply pleased if it has helped to encourage the young people that have followed our generation to express their pride in our heritage more openly, more joyfully than I would have ever dared to think possible."[22]

Roots (7.5.38) became one of Odjig's most famous paintings. Created in three sections, the first one portrays the peaceful life on the reserve where she lived. The middle panel depicts the disorientation felt when leaving the natural home life of the reserve. The headless back of the woman appears to be moving towards the city, two floating heads wondering which world they live in. The third section is a complete woman, the trees in the background; she appears to know herself and is still attached to her roots. The sections are defined with strong lines to form the curved contours, the shapes overlapping. Odjig used bold, bright colors, ensuring each small section was distinguishable.

Alex Janvier

Alex Janvier (1935-) (Dene Suline & Saulteaux) was born on Le Goff Reserve in the northern part of Alberta. He was sent to the residential school when he was eight, a place where the principal recognized his artistic abilities and encouraged Janvier to focus on art. He attended the now the Alberta University of the Arts and was the first of the First Nation artists to graduate from an art school. He was also an instructor at the school. In 1966, he was commissioned by the government to produce paintings. He joined Norval Morrisseau and Daphne Odjig to form the Indian Group of Seven. Janvier created a new type of abstraction based on his heritage and Alberta's natural and spiritual life. Many of his works were large-scale and followed abstract patterns he found in the traditional arts of First Nation people's beadwork, quillwork, and how hides were painted. Janvier incorporated many political statements in his work, protesting the governmental policies against First Nation people and their freedoms. Janvier helped develop other Indigenous artists throughout his life and worked with the government to understand and accept Indigenous art as equal to other art. Janvier said, "Art truly is a universal language that can communicate any idea, any feeling, of anyone, regardless of their social standing, their religious beliefs or the language they speak."[23]

Morning Star (7.5.39) is one of his large paintings for a wall in the Canadian Museum of History. Janvier used free-flowing lines, as seen in calligraphy with bright, vivid colors. The surface of the building had to be washed, sealed, and coated with gesso. They used nine coats of white paint as a primer before it was ready for color. After Janvier finished painting the mural, a sealer was applied. Janvier related that the morning star guided the people about when to leave camp in the morning and follow the direction of the selected star. The four areas of color, red, blue, yellow, and white, represent different times in his Native history. Yellow represented their early history when life was balanced with nature, the Great Spirit, and each other. The blue section stood for changes brought by the contact and invasion of Europeans, and the red was for revival and the feeling of optimism, a time of struggle yet a determination to define their future. White represented the promise of reconciliation, healing, renewed self-respect, and returning to a harmonious life in balance again. Janvier said of his work on the mural, "I am painting, and I am also telling the story of the way things happened to me and to my tribe and to my people and it's a true story."[24]

Thirteen Moons (7.5.40) is a story about time and the people's lunar calendar. The large mural spans thirteen panels, each panel a month for the customary Indigenous lunar calendar. The calendar follows the moon's cycles based on the thirteen times the moon comes and how the Indigenous people coordinated their lives. Janvier talked about how the twelve-month calendar was forced on them; it is not the way they defined time. The panels were placed in a large circle; circles were a shape Janvier frequently used in his work because the sun and moon, and life are circular. The panels created an almost ceremonial site as the images surround the viewer. The set of panels was made to be portable and travel through the country, educating all people about the relationship humanity has with the earth and the timeless traditions of the Indigenous people.

Bill Reid

Bill Reid (1920-1998) (Haida) was born to an American father in Victoria, British Columbia. His mother was a member of the Raven/Wolf Clan of T'anuu or Haida. Because of the oppressive laws from the Canadian Indian Act, Reid did not know anything about his Haida heritage. In his twenties, he went to his ancestral home to understand and connect with his family and Indigenous identity. Reid's maternal grandfather was a Haida silversmith and taught Reid about the ancestral art and traditions of the Haida. In 1951, Reid went to Vancouver with his wife, set up his studio, and salvaged artifacts, including old totem poles in abandoned sites. He also began making jewelry and sculptures in bronze and wood. Haida's essence, knowledge, and traditions were mainly lost from colonization and suppressive Canadian laws at the onset of his career. Reid spent a long time researching ethnographic information about the traditions of the Haida. He transferred the learned knowledge to his artwork based on Haida mythology, from jewelry to large sculptures. Reid took the information he found and brought back the fundamentals, beauty, and rich tapestry of the obscure and almost lost Nation. Although Reid lived with the results of colonialism, he tenaciously brought the Haida ways to life.

The Spirit of Haida Gwaii – The Jade Canoe (7.5.41) is Reid's most complex and largest sculpture. Thirteen different entities are crowded into the canoe, almost mythical Haida beings; Raven, Wolf, Eagle, Frog, Bear, Beaver, Dogfish, and Mouse. Three humans are also in the canoe, the Chief who sits in the center, the Bear Mother, and the person paddling the canoe. The occupants represent earth, sky, and the sea, linked and impacting the figure next to them. Wrapped in the skin of the Seawolf, the Chief in the center holds a staff carved with the Haida story of creation. Initially, the sculpture was commissioned in 1986 by the Canadian government for its embassy in Washington. However, at the time, the Haida people were protesting the government's practice of logging in the area, so Reid stopped the project to support the Haida. It wasn't until 1991 that the first casting occurred.

In Raven and the First Men (7.5.42), the Haida creation myth believes the Raven was on the beach and heard creatures in the large clamshell making sounds. The Raven opened the shell with his beak, and the beings in the shell emerged and became the first Haida people. The Raven discovered all the beings were men, so the Raven opened a chiton holding the women and brought them to the men. Reid tried to carve the image from a cedar log, except too many places were rotten. Instead, he used laminated yellow cedar beams, successfully creating the sculpture. When Reid talked about the beings in the shell, he said, "I see them as unformed, having all the potential of being human but having no way of achieving that until they emerged from the clamshell. And yet, of course, I depicted them as though they were of different personalities and different ages and so on."[25]

Rebecca Belmore

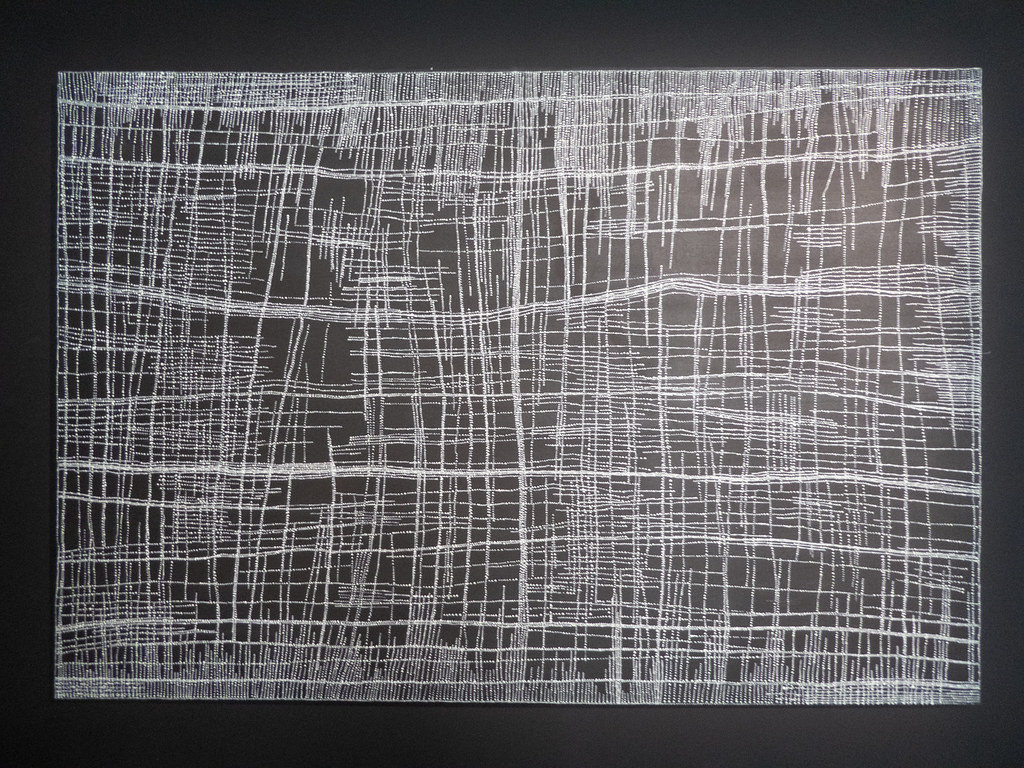

Rebecca Belmore (1960-) (Ojibwe of Obishikokaang) is a multidisciplinary artist who focuses on identity and social issues for First Nation people. As a child, Belmore spent summers with her grandparents, learning about native foods found on the land and how to harvest them. As a teenager, she was sent off to high school and resided with a non-Native family, losing contact with her culture. When Belmore went to Toronto and the Ontario College of Art, she entered an environment of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, encountering racism and influencing her future artwork. Belmore uses multiple media types, including photography, video, sculptures, and performance, to address political and cultural dissonance. Nuit Blanche or White Night is celebrated throughout Toronto, running from sunset to sunrise in different city spaces. In her Nuit Blanche performance (7.5.43), Belmore sat in the middle of a basement floor located in an art gallery. She applied clay in a grid format to the floor's marble tiles. In some areas, the clay is drying, then re-applied with Belmore's hands. She wore plain black clothing stained with clay. Belmore worked and moved across the clay, only stepping on dry clay, disassociated with the space outside of the floor. Her performance art is subtle to the viewer as Belmore worked from sunset to sunrise. Frequently, she wrote words first before covering them; water, land, breathe. Belmore focused on identity, the continual destruction of Indigenous life, and how they are represented.

Belmore generally used local or natural materials to create much of her artwork. Marble Tent (7.5.44) was constructed of marble in Greece near the Acropolis. At the time, the refugee crisis escalated in Greece by people forced to flee their homeland like the Anishinaabe people who were dispossessed of their lands in Canada. The tent has long been a symbol for refugees, a makeshift retreat; also, the tent provides a shelter for those who follow the food sources. Belmore stated, "The shape of the tent is, for me, reminiscent of the wigwam dwellings that are part of my history as an Indigenous person."[26] Belmore defined the historical and current issues with Indigenous populations in Canada within the crisis of worldwide events and problems.

Tarpaulin No. 2 (7.5.45) was created when Belmore responded to the homelessness issues and problems in Vancouver, Canada, after encountering a homeless man. She met the man in a parking lot and gave him food. She said, …he offered me a smoke. I declined. Before I turned to leave, he asked me if I wanted an "Indian blanket." I accepted his humble gift, a small, plaid-patterned fleece blanket like the ones you can buy at Walmart."[27] Tarpaulin No. 2 represents the blanket in the story, suggesting a person lying beneath the blanket as the sculpture sits alone in the middle of the space. The homeless suffer the same fate, alone and ignored by passersby. Belmore also captured the disproportionate inequities of the homeless Indigenous population. The patina on the blanket is mottled as Belmore illustrates how blankets containing the smallpox virus were deliberately given to Indigenous Peoples in the era of colonization, spreading the devastating disease. Racial injustice continuing today is represented through a blanket.

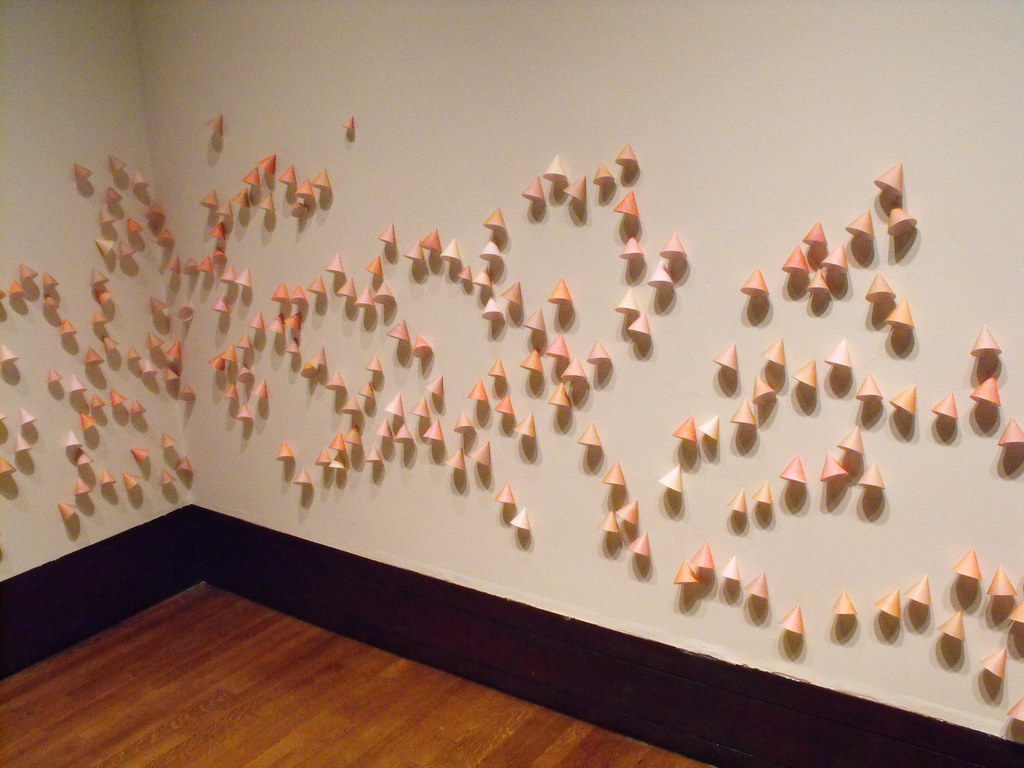

Faye Heavyshield

Faye Heavyshield (1953-) (Kainai-Blood) grew up on the Blood Reserve, one of twelve siblings. She went to a residential Catholic school when she was young, speaking English while maintaining her Blackfoot language. Heavyshield's grandmother was instrumental in teaching her about the traditions and history of the Blackfoot and Blood people. Her father managed a ranch, and Heavyshield was influenced by the geography of the land, its grasses, the river coulees, the flat plains, and blowing wind, all references she used in her art. After graduation with her BFA from the University of Calgary, Heavyshield focused her art on sculpture and installations. Heavyshield's heritage became a major inspiration for her work, along with feminism. She became one of Canada's leading feminist artists. Her work was also subjective of memories of the structure of bodies; the deer being skinned, the tepees' skin, and the bodies of the aged. Heavyshield stated, "When I began my formal art training, these influences surfaced in the form of biomorphic images, skeletal armatures with vestiges of flesh, using architectural and figurative language. Monochromatic, after the solitude and simplicity of the prairie. Sometimes building the surface up and then working back from there, peeling the layers."[28]

Kuto'iis (7.5.46) was inspired by the ancestral flow of history through Heavyshield's consciousness. She knotted hundreds of cloth pieces and attached them to an entire wall. The knots represent a blood clot and are randomly scattered; then, the whole installation was painted in red ochre. The repetitive knots represent the remembered knowledge of stories, language, and songs from multiple levels of history and ancestry. Heavyshield's sculptures are composed of numerous small elements arranged in lines or spirals, frequently an allegory for the human body.

Body of Land (7.5.47) is constructed of hundreds of close-up photographs of skin from hundreds of people. Heavyshield takes a photo, prints the photo, and rolls the image into a cone, spreading the cones along the wall in random colors. The soft rolling placement of the cones reminded her of the rippling hills of Alberta. Each cone is an exceptional closeup of skin linking the essential elements of the human experience, a sense of community interconnected. Heavyshield also felt the traditional wisdom of women was passed from mother to daughter, other female relatives, and the female connections with each other. Heavyshield said, "We are a product of Mother Earth, we come from her, we go back to her…As women, we are, in a sense, a smaller version of Mother Earth; we give life, we work, and protect."[29]

Robert Davidson

Robert Davidson (1946-) (Haida) was born in Alaska; his family moved to the Haida village in British Columbia when Davidson was still an infant. He belongs to the Eagle moiety with multiple relations who were woodcarvers. He became an apprentice to Bill Reid and studied at the Vancouver School of Art during high school. At the age of only twenty-three, Davidson carved a Haida Gwaii totem pole for the village of Massett. It was the first totem pole the village erected in over ninety years, a pole installed with Haida raising ceremonies.

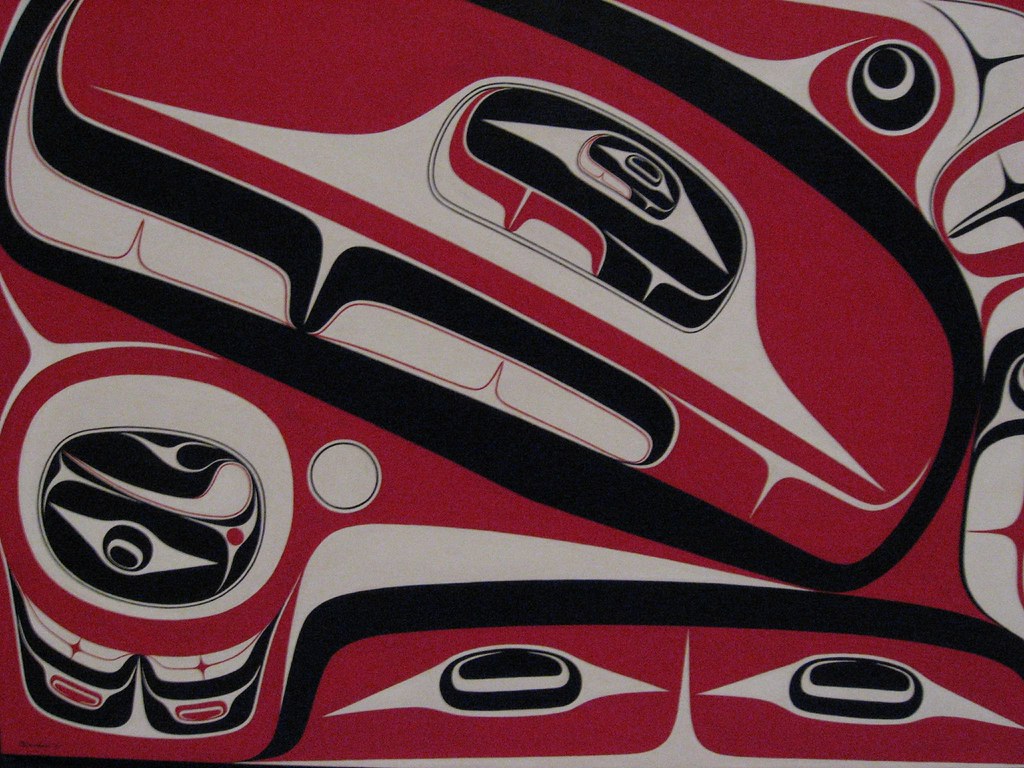

Along with carving, Davidson is a painter and printmaker consistently focusing on Haida traditions. One of Davidson's main artistic characteristics is his preservation and use of distinctive Haida visual language. The use of positive and negative spaces and the forming and ovoid shapes are found in his intensely graphic and abstracted style. Davidson claimed, "I draw on the lessons of our ancestors. Our ancestors left an incredible legacy of art and, to honor them, it's our responsibility to relearn that legacy…"[30] Haida art is characterized by broad and narrow flowing lines. The designs are flat, compact, and very organized with bright contrasting colors.

Davidson's Killer Whale (7.5.48) presents the ovoid-shaped staring eyes, the giant creature exposing his teeth. He follows the tradition of a form line with U-shaped figures joined and stacked as Davidson defined new shapes. Linked to different lineages, the killer whale is a famous crest and figure in Haida art and myths. Many believe the killer whale lives in the underwater realm, similar to humans on land as they travel in family groups. Davidson and others are part of a committee bringing claims against the Canadian government to repatriate ancestral artifacts, remains, and land taken from the Haida in the past.

Davidson had an exhibition entitled The Abstract Edge. One of the images, the World is Sharp as a Knife (7.5.49), is based on an old Haida expression meaning to move through life with balance. Davidson explored the world of abstraction within the constructs of traditional art images. Although abstracted using traditional forms, the image appears much like a conventional painting, with curvilinear shapes, lines, and colors.

Beau Dick

Beau Dick (1955-2017) (Kwakwaka'wakw) was born in northwest British Columbia and moved to Vancouver when he was six. His Kwakwaka'wakw name was Walas Gwa'yam, the word for Big Whale. Dick's small village homeland was very secluded; it is easiest to travel by boat even today. Because the area was so remote, during the Potlatch Ban of 1885-1951, the Kwakwaka'wakw people could still maintain their customs. Dick was immersed in their history. His grandfather and father were both woodcarvers who taught him the basics early before he started as an apprentice under master carvers in Victoria, BC. A commission to make a mask for Expo 86 in Vancouver encouraged him to focus on masks. His work was highly influenced by Kwakwaka'wakw history and traditional methods as he incorporated contemporary ideas and Western influences. Dick's masks were collected as art while still being used for ceremonial activities in the community. He believed if the mask was not used in a dance, the mask's spirit was not activated. DIck also was active in many of the region's activist groups, speaking and acting for his community. He always talked about responsibility and respect and how we need to strive for healing. Dick made all types of masks, some with his traditions and others based on Japanese anime, Halloween, or Noh masks. He carved the masks (7.5.50, 7.5.51) from wood and added different materials. Dick used all materials for his masks, including wood, string, straw, feathers, paint, leather, fur, horsehair, shells, copper, and bark. Some of his masks were made for ceremonial dances and were burned after four years. Other masks were sold or otherwise used.

For centuries, people have thought of Indigenous Peoples' art as part of the past ethnographic record of the cultures from the original peoples. By the beginning of the 20th century, Native arts were kept as a subtext of the past, outsiders controlling the narrative of art for Indigenous Peoples. Creating fine art with the ideals or constructs of modern theories was not acceptable. After World War II, the world changed, and as countries emerged from colonialism, the geography of the world transformed. Newly found freedoms and education led Indigenous artists to experiment with abstraction and emotional, challenging images, changing art for Native cultures worldwide. Some artists created art without any Indigenous themes. However, most Indigenous artists worldwide incorporated their past traditions and cultures into new concepts and artistic ideas, paying homage to the past and their lands with the contemporary visions of the future. However, the general future many Indigenous Peoples in all the regions still face is continually ranking below the general population in poverty, economic prospects, and educational opportunities. Even those with independent governments continue to encounter economic erosion, discrimination, environmental degradation, and the effects of climate change as sea levels rise.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/i...enouspeoples#1

[2] Retrieved from https://equity.ucla.edu/know/resourc...-peoples-faqs/

[3] Retrieved from https://www.iwgia.org/en/usa/3640-iw...f-america.html

[4] Retrieved from https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/.../1529102490303

[5] Retrieved from https://samblog.seattleartmuseum.org/2020/12/leaves/

[6] Retrieved from https://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/u...ame-kngwarreye

[7] Retrieved from https://www.mca.com.au/artists-works...d-and-the-new/

[8] Retrieved from https://viewing.nyc/check-out-metrop...er-collection/

[9] Retrieved from https://larsongallery.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/TERRAINCatalog4.pdf

[10] Retrieved from https://folklife.si.edu/magazine/cri...-naranjo-morse

[11] Retrieved from https://cla.purdue.edu/academic/ruef...n/naranjo.html

[12] Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart...eum-180978969/

[13] Retrieved from https://massmoca.org/event/wendy-red-star/

[14] Retrieved from https://www.crockerart.org/collectio...oke-feminist-1

[15] Retrieved from https://www.denverartmuseum.org/es/node/10487

[16] Retrieved from https://artnewengland.com/?s=Tarlow....New+England.+9.

[17] Retrieved from https://www.okeeffemuseum.org/explor...-to-see-smith/

[18] Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/state-names-73858

[19] Retrieved from https://www.culturalsurvival.org/pub...rt-rick-bartow

[20] Retrieved from https://www.americanindianmagazine.o...ow-cedar-poles

[21] Retrieved from https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/nor...eau/biography/

[22] Retrieved from http://odjig.com/profile.html

[23] Retrieved from https://www.gallery.ca/whats-on/exhi...enous-master-0

[24] Retrieved from https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exh...re/283eng.html

[25] Retrieved from https://moa.ubc.ca/wp-content/upload..._First_Men.pdf

[26] Retrieved from https://www.rebeccabelmore.com/biinj...i-from-inside/

[27] Retrieved from https://www.sfmoma.org/essay/rebecca...arpaulin-no-1/

[28] Retrieved from https://www.gallery.ca/collection/ar...ye-heavyshield

[29] Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=Cw...shield&f=false

[30] Retrieved from https://thecontemporaryaustin.org/ex...son-u-and-eye/