5.5: American Modernism (1910-1935)

- Page ID

- 120759

Introduction

American Modernism reflected the worldwide changes in art based on the unique American culture. The movement, along with others in this period, aligned with the experiences of modern industrial existence. Artists rejected the realistic approach of art and moved to more abstraction, experimentation with color and shapes. Artistic themes were based on social agendas, emotional feelings, and political changes. Art was varied, the personal expression of each artist as they created new visions.

Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986) was born in Wisconsin on a wheat farm. She was interested in art from an early age, studied art in high school, and attended the Art Institute of Chicago. After moving to New York, O’Keeffe continued to study traditional art methods until learning the concepts espoused by Arthur Dow. He believed art should be expressive and composition composed of harmonious lines, mass, and colors. These ideas influenced O'Keeffe to develop more abstracted drawings, a way to express her feelings. One of her friends took her drawings to show to Alfred Stieglitz, a famous photographer who owned his art gallery. In 1916, he started to exhibit her paintings, and by the mid-1920s, she was acknowledged as a very successful artist, well-known for her oversized depiction of flowers. Her work placed her as a significant practitioner of American abstraction, a difficult achievement for a female in a male-dominated art world. O'Keeffe developed her style, maintained her vision, and was not deterred through her life by other movements and trends of the art world.

O'Keeffe married Stieglitz in 1924 as he continued to promote her work with multiple shows and installations. She left New York to travel through New Mexico in 1929, a place she was enthralled with and inspired by; the stark desert landscape, the native cultures, and the region's architecture generated new ideas and directions for her art. O’Keeffe traveled between New York and New Mexico to work, permanently moving there in 1949 after Stieglitz died. She painted different scenes throughout New Mexico, traveling internationally to depict mountain regions in Peru and Japan. Although she suffered from macular degeneration, as her vision failed, she continued to paint images in her memory until she passed away at age 98.

O'Keeffe was first known for her incredible close-ups of flowers. Georgia O'Keeffe believed that people merely glance at flowers but never really observe their exquisiteness due to people's fast-paced lives. She wished to give such rushing people experience and the feel of the true beauty of flowers. In her words, "If I could paint the flower exactly as I see it, no one would see what I see because I would paint it small like the flower is small. So I said to myself - I'll paint what I see - what the flower is to me but I'll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it - I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers."[1] She was exceptionally observant, noticing the subtle shapes, lines, and colors of her subjects. Flowers became the theme of her first major set of paintings, focusing on a small flower that filled a large canvas, appearing abstract although a perfect representation of the flower with enhanced bold color and texture.

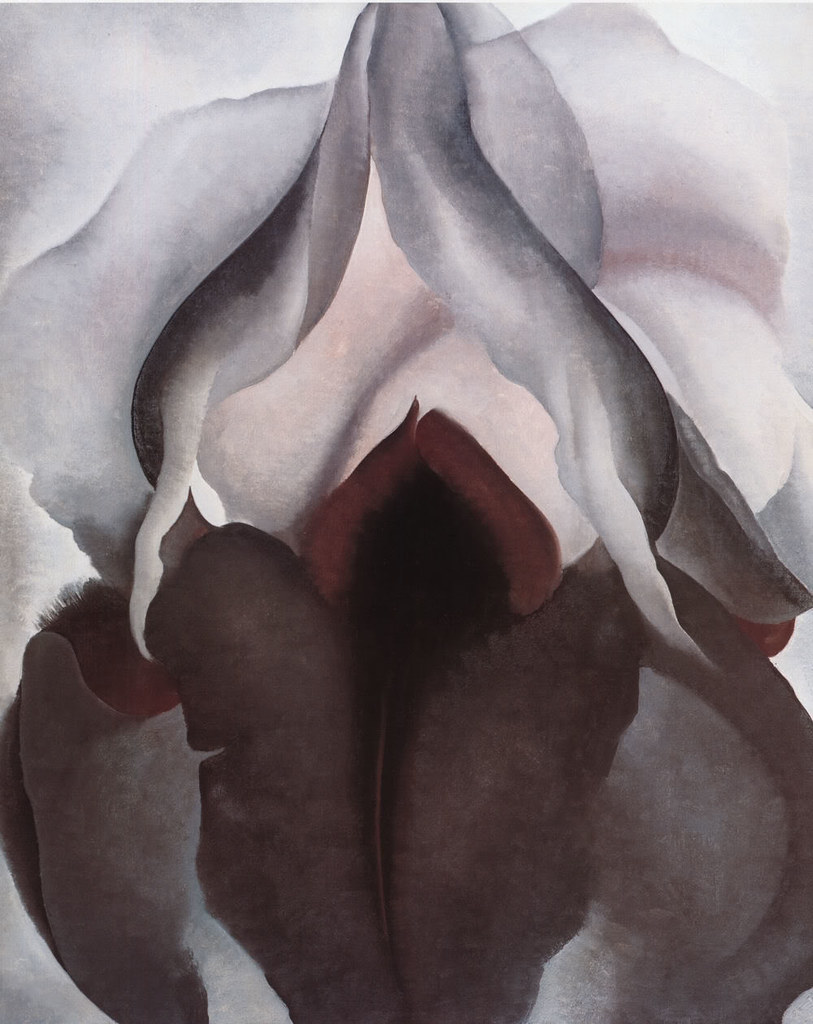

Black Iris (5.5.2) is a close-up of an iris; the flower perfectly reproduced on canvas while engendering a possible abstracted image of a person with their hands overhead. The dark, rich colors draw the eye into the center of the flower as the petals unfold into an almost transparent pink.

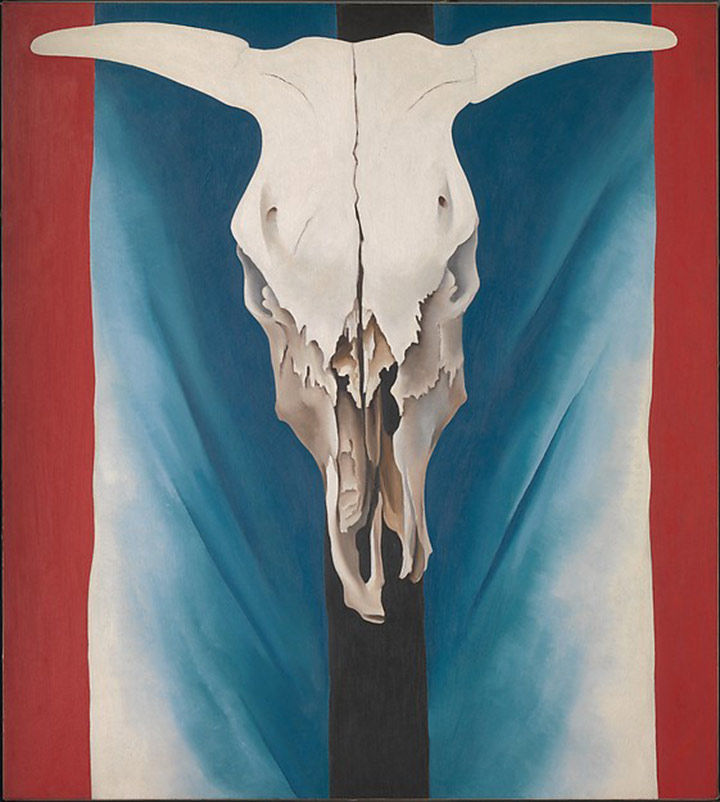

On her early trips to New Mexico, O'Keeffe became enamored with the animal bones she found in the desert landscape, bones bleached by the sun and weather. In Cow's Skull: Red, White, and Blue (5.5.3), the jagged edges of the skull's bottom half contrasted with the smooth, weatherworn top half. She believed the skull represented the long-lasting and enduring beauty of the desert, the red, white, and blue background symbolizing the American spirit. She painted several different versions of skulls and bones throughout her time in New Mexico. The spectacular landscape and scenery of the rocks and mountains of the variable desert settings were a major inspiration for O'Keeffe. Near the house she purchased at Ghost Ranch were brightly colored hills of different hues.

Red and Yellow Cliffs (5.5.4) exemplify the incredible mountains rising from the desert floor. The striated precipices were eroded over centuries revealing the dynamic red and yellow colors. Sparse greenery dots the desert floor, growing where the minimal amount of water collected. These mountains were the subject of multiple paintings.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Red and Yellow Cliffs (1940, oil on canvas, 61 x 91.4 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Red and Yellow Cliffs (1940, oil on canvas, 61 x 91.4 cm) Public DomainThomas Hart Benton

Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975) was born in Missouri in a family active in politics, his father a U. S. congressman and a great-uncle who was of the first senators from Missouri. Benton lived in both Missouri and Washington D. C. He went to a military school to hone his skills for a political career. However, Benton wanted to study art, his mother encouraged the concept, and he went to the Art Institute in Chicago, then to Paris for further study. During World War I, Benton was in the navy; his job was to draw camouflaged ships in the Virginia harbor, ensure the vessels were properly painted with the correct camouflage patterns, and create an inventory. He was married for over fifty years with two children. After the war, he moved to New York to paint, developing a frequently termed regionalism style, exalting rural America, and denigrating abstract art. Initially, he studied modern art and decided he did not like abstract work, preferring to create a representational and more naturalistic style. He traveled throughout the country, taught for a while in Kansas before moving back to New York. He trained many well-known artists, including Jackson Pollock, who started the Abstract Expressionist movement. Pollock always claimed the traditional work of Benton gave him a reason to rebel against the ideas of representational art.

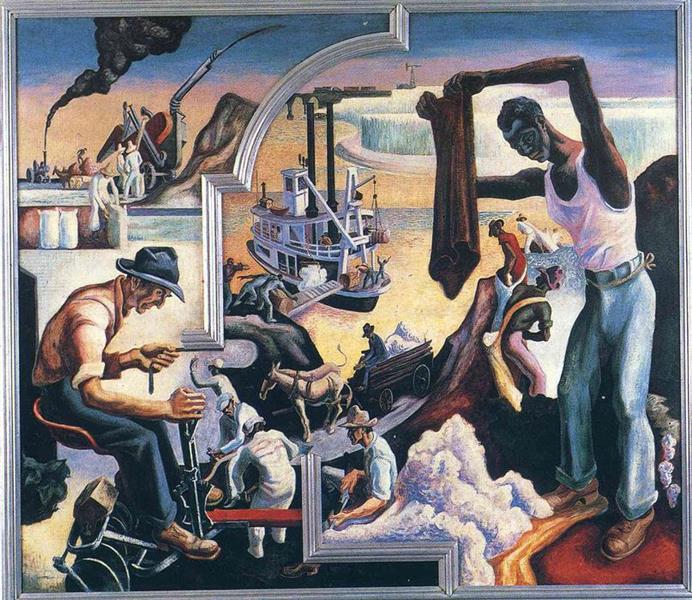

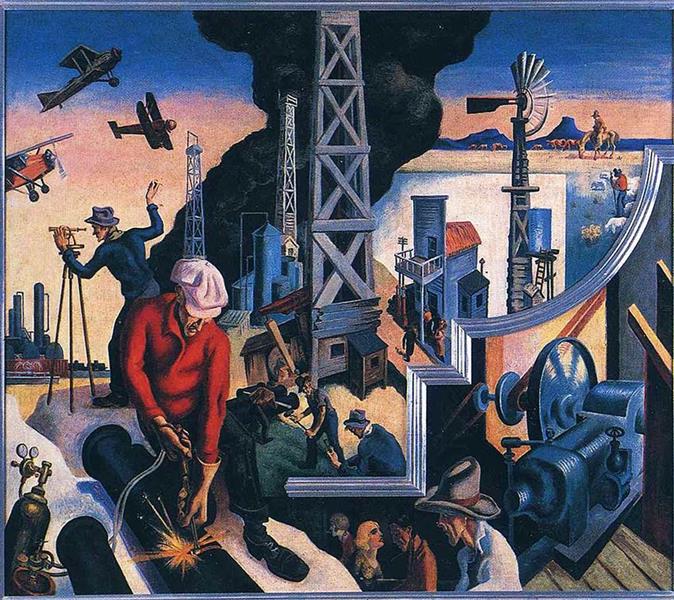

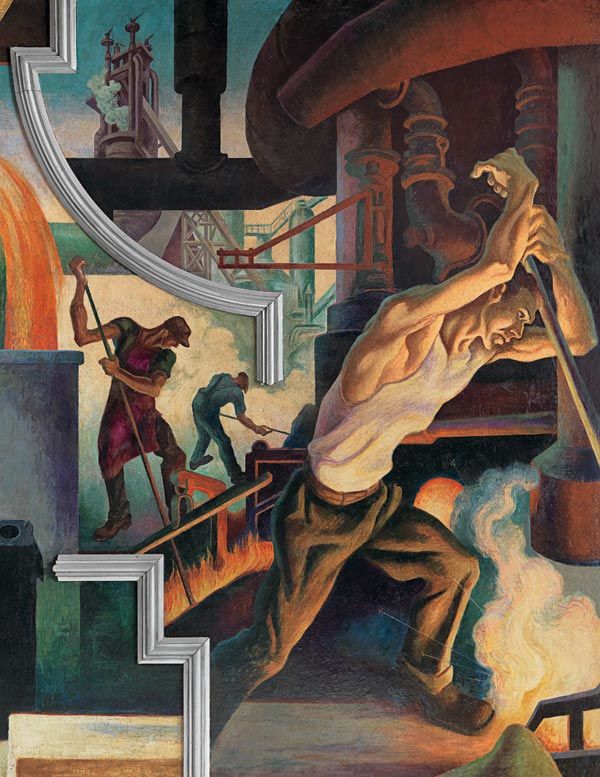

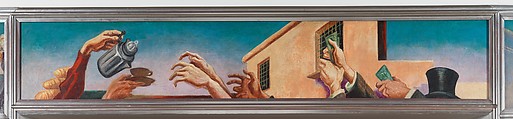

Benton's most famous work was America Today, a set of ten oversized canvas panels from floor to ceiling covering all four walls, painted for the New School for Social Research boardroom in 1931. He used egg tempera and an oil glaze over Permalba and gesso on the linen-mounted wood panels. Benton agreed to create the murals without any compensation except for the materials he needed. He stated, "I'll paint you a picture in tempera if you finance the eggs."[2] He hoped the work would grow his reputation and obtain other commissions. Benton had traveled throughout the United States, making sketches as he journeyed to create an extensive view of American life. Some of the panels represented different regions of the United States including, Midwest (5.5.5), Deep South (5.5.6), and Changing West (5.5.7). Other panels portrayed life in specific occupations, as seen in Steel (5.5.8). The smallest panel was Outreaching Hands (5.5.9), some reaching for food and others for money, relating to the extreme economic dire of some and the inequity of the moneygrubbers in the Great Depression.

Despite the Depression, Benton wanted to portray a vision of the country's progress based on the new technologies and industries. He also believed progress was generated by the work of the people, their physical participation, and struggles. Each panel is filled with workers, large muscular physiques dressed in everyday clothing, and exaggerated positions and expressions. He was a master of arrangement, using strong diagonals to partition sections and move the eye through the narrative of the painting. Benton also used wood moldings covered in aluminum leaf to create spatial breaks while unifying each panel, the moldings similar to the Art Deco décor of the building where they were installed. The mural Deep South was based on cotton, the king of industries in the south as the tall form of the black man looming over the scene empties his bag of cotton, the white man moving the cotton with a plow, the guard overseeing the chain gang, cotton loading onto the steamboat. Midwest depicts the lumberjacks as they clear-cut the forest, emptying the land to grow corn, the grain elevator occupying the skyline, Benton's Ford hidden in the background. Changing West is the image of the Texas oil boom with thick smoke and a dominating derrick, the vanishing cowboys smaller in the setting. Steel is based on a single industry, displaying the depth the workers performed, power, and strength a requirement. He also included murals of other discrete industries. Benton demonstrated his attention to detail as he traversed the United States, recording the workers, the complexity of their jobs, and the dominant industries of the country while adding the details of the changes of life he observed.

Edward Hopper

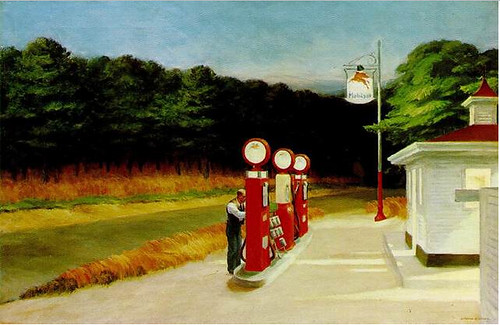

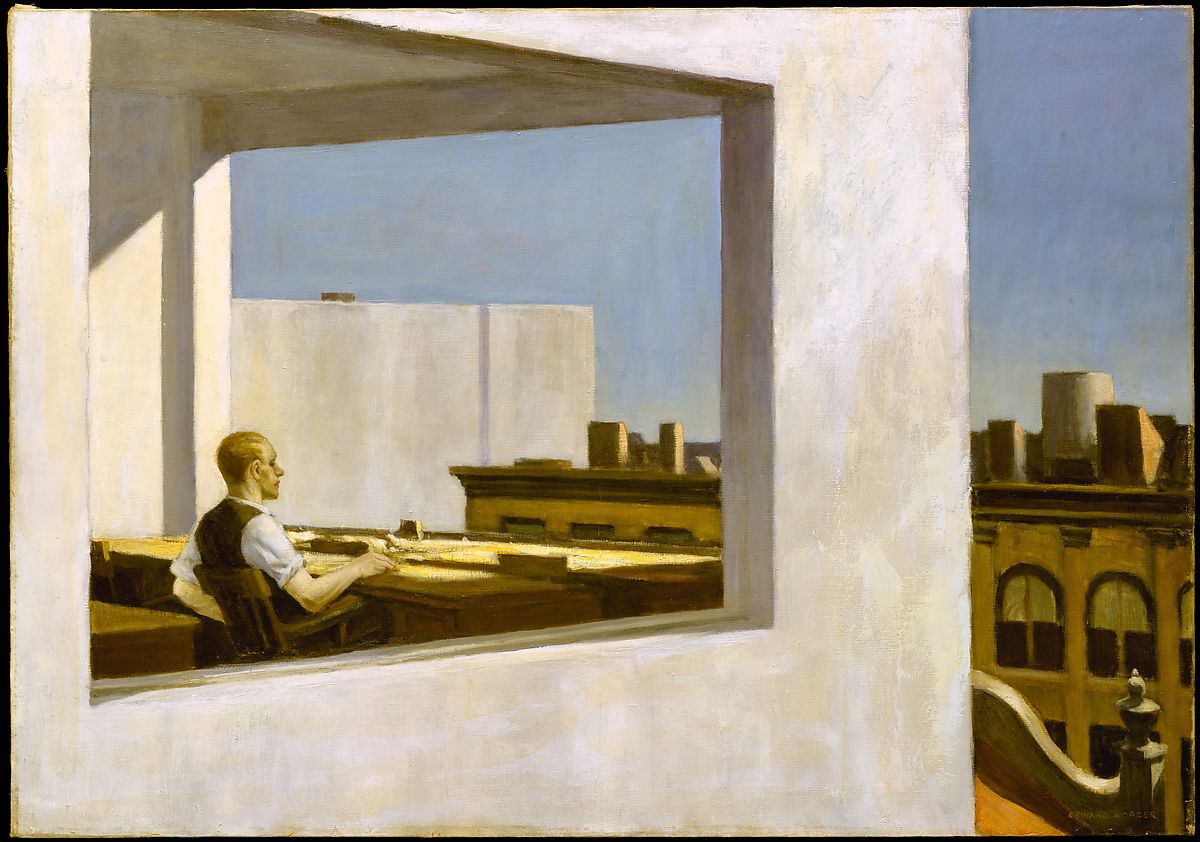

Edward Hopper (1882-1967) was born in New York; his parents were from an established Hudson River family. He began drawing at an early age and, after high school, went to the New York School of Art and Design. After working as an illustrator, Hopper went to Paris to study, trying different techniques, deciding he didn't want to use any particular style, only his own, uninterested in the abstract art of the time. Hopper returned to the United States, working for several years before he achieved success. He married, and his wife successfully helped promote his work. Hopper, well-known for his oil paintings, started any work with careful sketches, focusing on geometrical design, the balance of each element, and how any figure appeared in a painting. He also concentrated on light, whether natural or artificial, using light to cast specific shadows and create the mood of a painting. Hopper primarily painted images of American life and the structures inhabited by people, for example, a motel room, an office space, or the waiting room at the station; the buildings of ordinary life and how people were perceived in spaces along with the interaction of light in a space. Hopper incorporated emotion into his work with a limited number of figures, positioned in an environment to elicit feelings of loneliness or boredom, emotions enhanced by his use of light. He also painted sea things: crashing waves, lighthouses, boats on the water, or grasses on the shore.

Gas (5.5.10) represents the rural station, dusk setting in as the solitary attendant checks the pumps, perhaps ready to close for the night. Hopper used both the natural light of the darkening sky and the artificial light of the station. The road is empty, depicting the solitude of the country road, the gas station a refuge for the traveler who stops for gas or directions, the light a beacon on the road.

Hopper brought his emotion into seascapes, The Lighthouse at Two Lights (5.5.11) standing starkly in silhouette against the dimming sky. The sun is low on the horizon casting its light on the face of the walls with deep shadows. The sturdiness of the lighthouse demonstrates its resistance to nature, standing for decades. Hopper uses a limited palette, the gray building against the muted gray sky, the fields dried by late summer, adding to the feeling of loneliness and isolation.

Tables for Ladies (5.5.12) was based on the newly available ability for ladies to dine at a restaurant without a male in attendance. Previously, women dining out were presumed to be prostitutes. Hopper portrays each person in isolation without interaction; the cashier only focused on her register, the waitress rearranging the food as the couple sits in the background. The painting allows the viewer to peer through the window, watching the scene in front of them. Hopper's attention to detail is visible in the precise method the table is arranged. The foreground is brightly colored, grabbing the viewers' attention, the couple in muted, simple colors almost disappearing into the background.

Office in a Small City (5.5.13) conveys the isolation and seclusion of the man sitting in his office. The stark concrete building removes him from the outside world; a world only viewed through the soundless windows. Hopper's wife described the painting as "the man in concrete wall."[3] Hopper used the immensity of the corner office walls and window in juxtaposition to the small person bringing the isolation of the person from the humanity of the outside, others only visible through the glass.

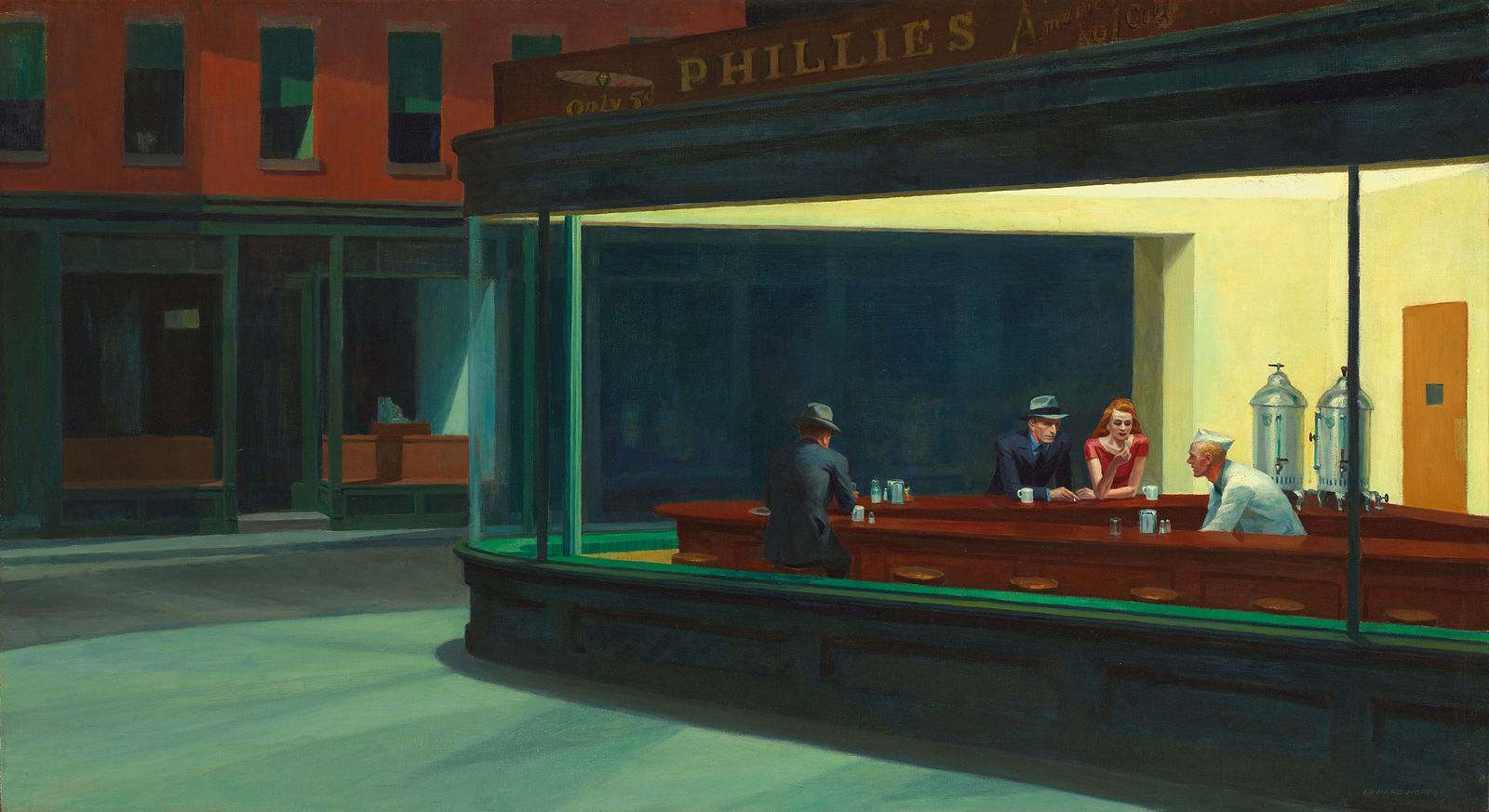

Nighthawks (5.5.14) is one of Hopper's most famous paintings. The inspiration for the restaurant was in New York; however, the construction of the painting places the scene in anywhere America, the universality of the lonely late-night panorama. The painting is an outstanding demonstration of Hopper's use of light. Fluorescent lighting was new in the 1940s, giving an eerie luminosity to the diner's interior positioned without any visible entrance. The large window gave the viewer an intimate look at the remote activities of the people inside. Hopper's use of a green palette enhanced the glow of the light through the window.

Marion Beckett

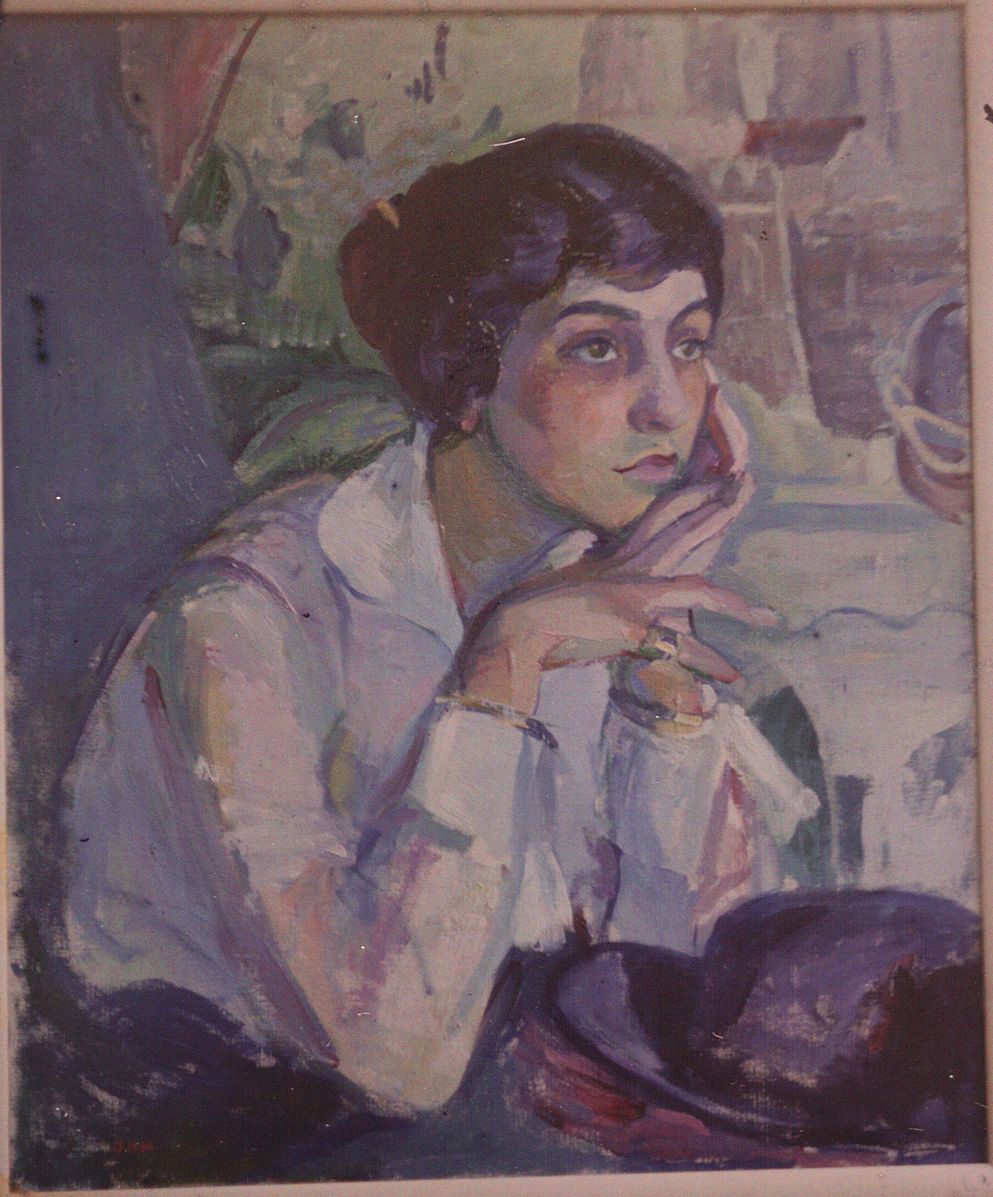

Marion Beckett (1886-1949) was born in New York, receiving a large inheritance after her father's death and giving her the freedom to travel to Paris and study art with her life-long friends Agnes Meyer and Katharine Rhoades. Beckett was described as exceptionally beautiful and shy. She mainly painted portraits and exhibited at Alfred Stieglitz's gallery, along with her friends, where they were given the nickname "The Three Graces." Beckett and the other women were in a transitional period, the ideals of Victorian femininity replaced by new opportunities and expectations of behavior and dress. She was successful as an artist, showing in many galleries; however, she stopped painting in 1926. She and her friends frequently went to France, visiting photographer Edward Steichen and his wife to paint their portraits. As World War I started, the German army invaded Steichen's house, and Beckett and the Steichens escaped two days before. After the war, Beckett created a studio in Paris, where she supposedly had an affair with Eduard Streichen. In 1919. Beckett was sued by Clara Steichen for $200,000, claiming "alienation of affections." When testifying against Beckett in court, she asserted, "Miss Beckett, when my husband was near, would wear nothing but long, clinging gowns and roses…She dressed in a very artistic or theatrical manner to attract attention and exploit her physical charms."[4] Clara Steichen could not prove anything and lost the case. The paintings of the couple seem to reflect their feelings. Clara Steichen (5.5.15) is not facing the artist, looking dejectedly to the side. The paint colors are very grayed and muted tones respond to the saddened state of the woman.

Eduard Steichen (5.5.16) is looking directly at the artist, a slight smile on his face. The colors in the painting are more dynamic and alive.

Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) was born in New Jersey; as a teenager, he and his family moved to Germany. When he studied engineering in Berlin, he became interested in photochemistry and traveled across Europe photographing the sights with a newly purchased camera. In 1890, Stieglitz returned to America, working in New York to improve the newly established community of photographers. He devoted his time to pioneer new techniques in photography, particularly improving methods to create photographs in poor weather, rain or snow, and the darkness of night, not just snapped images, rather compositional scenes. Stieglitz wanted to improve the perception of photography as an art form and opened the first of his galleries, including "291," and published the Camera Work magazine. He incorporated the new contemporary work created in Europe by artists in his gallery, expanding his reputation.

He also met Georgia O'Keeffe when a friend took her drawings to the gallery at 291 and, by 1917, developed a relationship with O'Keeffe, changing the focus of his work. O'Keeffe moved to New York to work in a studio Stieglitz provided. As Stieglitz changed his style, he moved from an encapsulated scene to the modern ideas of fragmented parts, only capturing partial sections of any scene. O'Keeffe was his primary model, and he took over three hundred images of her, often nude, focusing on her hands, neck, or other divided parts of her body, capturing emotional poses instead of the usual flat portrait. They also had what others described as a torrid affair. Stieglitz's wife divorced him, which took six years to settle after lengthy legal battles, then he married O'Keeffe. By 1921, he held a major exhibition of his photographs, including almost fifty of O'Keeffe, furthering his reputation as an artist-photographer. Stieglitz began showing and successfully selling American artists' work at the gallery, including O'Keeffe's work.

When Stieglitz died in 1964, O'Keeffe selected over 1,600 photographs she considered his major work and donated them to the National Gallery of Art, the most extensive collection of his photographs.

The Terminal (5.5.17) was one of the early photographs Stieglitz took, marking the beginning of elevating photography as an art. He used a smaller 4 x 5 camera instead of the larger sizes requiring a tripod. With the small camera, he could move around the city and capture images as they occurred. The techniques transformed photography from posed, still images to more painterly scenes. He captured the steam coming from the horses releasing heat in the cold, snowy weather giving the image the look of a painting instead of the pose.

The Steerage (5.5.18) depicts immigrants from Germany landing in New York. Stieglitz captured the people as they lived aboard the ship, jammed in the steerage decks, the lowest level on the ship with little ventilation. The early photographs of Stieglitz are generally of the people in the lower classes, workers, immigrants, those toiling in the factories. As he evolved, he became interested in line and form.

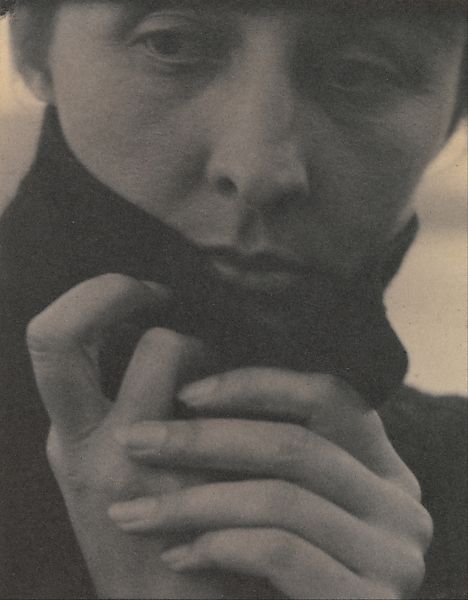

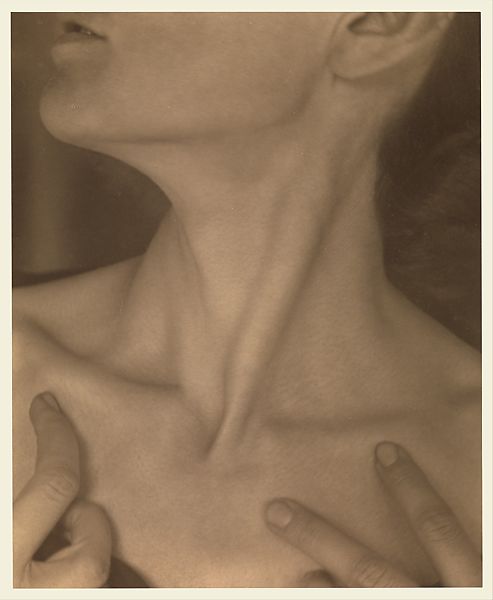

The two images of Georgia O'Keeffe were part of the three hundred photographs Stieglitz took of her from 1917 to 1937. In each image, Georgia O'Keeffe (5.5.19) and Georgia O'Keeffe—Neck (5.5.20), Stieglitz demonstrates his concept of a portrait composed of more than the image of a face. He wanted the portrait to capture the person's story and express their emotions, movements, feelings, life's essence. He stated, "To demand the portrait that will be a complete portrait of any person is as futile as to demand that a motion picture be condensed into a single still."[5] In the first image, O'Keeffe's hands and face against the dark sweater, two distinct segments of the person bring a complete feeling of her thoughtful emotion into the image. The second photograph of her neck and the partial face and hands presents a different feeling and set of expressions. O’Keeffe said of Stieglitz;

"Stieglitz photographed me first at his gallery "291" in the spring of 1917. … My hands had always been admired since I was a little girl—but I never thought much about it. He wanted head and hands and arms on a pillow—in many different positions. I was asked to move my hands in many different ways—also my head—and I had to turn this way and that. … Stieglitz had a very sharp eye for what he wanted to say with the camera. When I look over the photographs Stieglitz took of me—some of them more than sixty years ago—I wonder who that person is. It is as if in my one life I have lived many lives. … His idea of a portrait was not just one picture. His dream was to start with a child at birth and photograph that child in all of its activities as it grew to be a person and on throughout its adult life. As a portrait it would be a photographic diary." Georgia O'Keeffe, 1978[6]

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) was born in Wisconsin, his father a musician and minister, his mother a teacher. As a young child, his mother was interested in the Froebel theory of education based on the concept that children should master drawing basic geometric forms before drawing the spontaneous images found in nature. She bought him a set of geometrically shaped educational blocks able to be assembled in different three-dimensional combinations. For several years of his early education, Wright sat and drew lines and shapes based on the wooden blocks, constructing patterns and designs. The wooden blocks had a significant impact on his future, and he wrote, "…the smooth cardboard triangles and maple-wood blocks were most important. All are in my fingers to this day."[7]

Before he left, Wright attended the University of Wisconsin, moved to Chicago, and worked as a draftsman with an architectural company. He worked for other firms, starting to design houses on his own at night. Wright was fired from his job with one firm because they discovered he was also working on commissions outside their company. He attributed his need for money to his poor financial acumen and expensive tastes. Starting his own company, Wright designed houses with geometric constructs and features with open floor plans or rows of windows for several houses in the Chicago area. Wright married and had six children. From 1900 to 1914, he designed homes identified as the Prairie Style, a more organic architecture. Others who wanted to improve smaller houses with better design noticed his concepts, allowing him to expand his scope and business. Wright's prairie designs usually included low-pitched roofs, strong lines on the horizontal planes, open floor plan instead of boxy rooms, the building with a longer form instead of the squarer bungalow types, and the use of stone and wood natural materials. Meanwhile, his personal life was spiraling, and he divorced his wife, marrying two more times as his second wife died after one year of marriage. He also lost his Taliesin studio in Wisconsin when a servant killed seven people in the living quarters or working outside, then set fire to the building.

Wright designed a revolutionary style of a concrete block system in the 1920s. The blocks were premade with a set of internal bars for assembly. The prefabrication allowed builders to order any color or texture for the easy to assemble blocks. He updated the system after World War II when he was designing the Usonian-style houses. Usonian homes (5.5.21) were usually constructed in Wright's typical flat roofs, a radiant heating system incorporated into a concrete slab floor, and open floor plans. In the 1930s, Americans seldom had servants, so Wright designed the houses with a kitchen open to the dining room, a 'workspace' for a woman to monitor the children or her guests. The living area was the focal point with a large fireplace, the bedrooms small and isolated. After the war, the new design was popular for developers to build homes with mechanized and simpler construction methods.

In 1934, Wright struggled financially after the stock market crash, depression, and bank failures; private homes were no longer constructed. He was also becoming a relic, unwilling to follow the newer developing European trends. He did create an apprentice program attended by the son of a wealthy Pittsburgh businessman, Edgar Kaufmann. Upon recommendation from his son, Kaufmann hired Wright to build a vacation home in the woods of Pennsylvania. Wright designed Fallingwater, inspired by the natural environment surrounding the site; he incorporated all of nature's beauty in the organic architecture for the materials and colors. Fallingwater (5.5.22) was noted as one of the best structures of American architecture.

Wright's clients loved the natural setting, and he wanted to change as little of the surroundings as possible, including retaining the stream and the waterfall in its natural position. He attached reinforced concrete projections (5.5.23) to the natural rock to hold the cantilevered terraces (5.5.24) made from local stone, blending in with the existing sandstone, seemingly floating above the stream.

The first-floor entry, living, and dining rooms (5.5.25) are open in one contiguous space with broad glass windows. The living room houses the door to the stairway descending to the stream. Wright also incorporated a large rock outcropping into part of the living room, leaving the rock undisturbed. Guest rooms were located above the main house. Uniquely, no windows face the falls, all of the windows are oriented to the trees and horizon.

Wright went to Arizona in the winters, leaving the Wisconsin winters because of his health. In 1937, he bought land for Taliesin West, named after his studio in Wisconsin. When they were excavating the property for the building, they found Native American (Hohokam) petroglyphs appearing to be clasped hands. He used the interconnection of the lines for his building, now the symbol for Taliesin West (5.5.26). He wanted the design to compliment the desert and made the walls with desert rock inserted into the concrete, generally referred to as 'desert masonry.' The flatter surface of the stones faced outward, the larger part of the stone evident in the interior space. He used his concept of the long, low-hanging roofline to protect the walls from the hot desert sun. He added other facilities and rooms throughout the years, including the theatre's hexagonal shape and perfect acoustics.

The Garden Room (5.5.27) is a long meeting space with a glass roof open to the stars and seating along with expansive windows. Wright believed the view was key to the beauty and aesthetics of the site, and in the 1940s, when nearby power lines were going to be installed, he fought against it.

When he lost the battle, he rebuilt the entrance (5.5.28), moving it to the rear of the existing structure without the offensive view of lines.

Julia Morgan

Julia Morgan (1872-1957) had a long and prolific career as an architect and engineer, designing over 700 buildings, including the famous Hearst Castle, also known as San Simeon. She was born in California, the family living on the west coast. Her New York grandfather was wealthy and helped support the family. When he died, her grandmother moved to California to live with the Morgan family, bringing her wealth with her. Morgan excelled in school and went to the University of California at Berkeley, majoring in civil engineering. During this period, none of the schools on the West Coast had an architectural program, so she chose engineering. When she was a senior, one of her professors encouraged her to go to Paris and attend the L’École Nationale et Spéciale des Beaux-Arts. Morgan went to Paris and twice failed to pass the entrance exam, learning they failed her deliberately because they "did not want to encourage young girls,…Morgan wrote, "I'll try again next time anyway even without any expectations, just to show 'les jeunes filles' are not discouraged." [8] She finally was admitted, advancing through the first level in half the time. Morgan was the first female to obtain a certificate from Beaux-Arts in architecture.

After she received her certificate in 1904, she returned to California and opened an office in California. After the earthquake and extensive fire, she received commissions helping to rebuild San Francisco, including the Fairmont Hotel. In this job, she continued to receive comments about women who should not be architects. Her success at the Fairmont led to multiple other commissions. From the time she first opened her office until she retired in 1951, she designed and supervised the construction of over 700 projects, a few in other states. Still, the majority of the projects were in California. She designed sixteen YWCA buildings, private houses, Asilomar in Monterey, and many structures for the Hearst family. In 1919, she met with William Randolph Hearst as a potential client to build his concept of San Simeon; he wanted something different than the usual California style. The commission for Hearst Castle (5.5.29), which he called 'the ranch,' led to a long-time association between Morgan and Hearst running from 1919 to the mid-1940s.

Morgan designed La Casa Grande, as part of Hearst Castle, with 115 rooms as the main building; its construction started in 1922 and continued until 1947, a building still unfinished. Guesthouses (Casa del Mar, Casa del Sol, and Casa del Monte) were connected to Casa Grande (5.5.30) by walkways and terraces. The façade of Casa Grande is four stories, similar to a building in Seville. Although constructed with concrete, the façade was covered with stone. The large overhang was made with teak Morgan found in San Francisco, purchased initially for a ship. Casa Grande did not have an elegant staircase leading to the upper floors, only elevators, and stairs. Morgan used the latest technology; a sound system wired throughout the building, radio stations, and eighty telephones located around the buildings and grounds and interconnected with a PBX switchboard, all advanced concepts for the time period.

In addition to the major set of buildings with their rooms and guest suites, the site also included indoor and outdoor swimming pools, a theater for movies and live shows, tennis courts, a billiard room, a wine cellar, two libraries, a zoo, dog kennels, airplane landing strip and hanger, thoroughbred horse ranch, riding trails and a five-mile pergola.[9] Based on the continual requirements by Hearst, the site continued to grow as Morgan designed the buildings and surrounding environments. Hearst did not want the native oaks touched, so work was sited around them; broad walkways and gardens connected the buildings, and spaces were designed for Hearst's art and antiques. One of the impressive rooms was the library (5.5.31). The ceiling came from a 16th-century house in Spain. Morgan used ceiling parts from different rooms and combined them into a single ceiling for the grand room. The large fireplace was made from carved limestone. Hearst had collected books and antiques for a long time and incorporated over 5,000 books into this room, adding over 3,000 in his study. Many of the books were special collections, first editions, or books signed by the authors. Hearst's extensive collection of ancient Greek vases were incorporated into the décor of the room.

The ceiling in the billiard room (5.5.32) was from a 15th-century Spanish building adorned with images of the courtly life of the time. On the wall hung immense Flemish tapestry millefleurs (thousands of flowers) dated around the 1500s and woven with wool and silk. The billiard room was a popular gathering spot for guests to play billiards or pool, and instead of the room being the customary domain of male guests, both men and women congregated and played.

The site had two pools, the Roman pool (5.5.33) made for indoor swimming and the outside Neptune pool (5.5.32). The Roman pool was built underneath the tennis courts and adorned with mosaics made from Murano glass tiles and gold leaf. The elegant pool was located farther away and not used very much despite its extraordinary beauty. The Neptune pool was called the most luxurious and extravagant pool ever constructed. Located along the edge of the hill, the pool is bounded by a low wall—integrated concrete struts throughout the pool to allow movement during an earthquake. The pool started as a decorative pond and expanded as a swimming pool. Extensive statuary, temple, and columns were added to complete the image of ancient Greece. The immense pool holds almost 350,000 gallons of water. To accommodate the guests, seventeen changing rooms were constructed nearby.

.jpg?revision=1)

.jpg?revision=1)

American Modernism is uniquely an American concept and design, illustrating the people and the country in the industrialized world. The art-recognized the economic growth and cultural changes in the country and the growing entry of female artists. The artists illustrated scenes of life found in the cities and the countryside, encompassing the people's emotions in ordinary lives and circumstances.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.georgiaokeeffe.net/oriental-poppies.jsp

[2] Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/story-behind-thomas-hart-bentons-incredible-masterwork-1-180953405/

[3] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/488730?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=edward+hopper&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=8

[4] Retrieved from https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Art/A_World_Perspective_of_Art_Appreciation_(Gustlin_and_Gustlin)/12%3A_The_Modern_Art_Movement_(1900_CE_%E2%80%93_1930_CE)/12.02%3A_American_Modernism_(1900_%E2%80%93_1930s)

[5] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/271615

[6] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/271570?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=Alfred+Stieglitz&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=4

[7] Wright, F. L. (2010). The Essential Frank Lloyd Wright: Critical Writings on Architecture, Princeton University Press, p. 368.

[8] Retrieved from https://lib.calpoly.edu/search-and-find/collections-and-archives/architectural/julia-morgan/

[9] Retrieved from https://lib.calpoly.edu/search-and-find/collections-and-archives/architectural/julia-morgan/