1.7: Mesoamerica – Aztecs, Mixtec, Maya (1400-1521 CE)

- Page ID

- 120728

Introduction

When Europeans arrived in Mesoamerica, the Aztecs were one of the most powerful Empires of the Americas, ruling an extensive area in central and southern Mexico and south into Guatemala. They were known as the Mexica, a nomadic people from Aztlan who spoke the Indigenous language, Nahuatl. We know them by the name Aztecs today due to a nineteenth-century German explorer named Alexander van Humboldt. In 1325, the Aztecs settled and built the magnificent city of Tenochtitlan on a swampy island on Lake Texcoco. The founding legend of Tenochtitlan was based on a prophecy of Huitzilopochtli, a chief god among their pantheon of gods. He directed the Aztecs to settle and build their city, where they saw an eagle on a prickly pear cactus emerging out of a rock. The name Tenochtitlan comes from the Nahuatl words tetl, meaning rock, and nochtli, which means prickly pear, a symbol used regularly.

The Aztecs drained parts of the swampy lands, built islands, and created acres of agricultural land. They also became the dominant force in the region in the 1400s, conquering other territories and building robust trading routes and partners. The civilization was based on a caste system; rulers, nobles, priests, merchants, farmers, servants, and the lowest group – the slaves. The Aztecs formed alliances with some groups and subjugated other groups by requiring tax, tribute, and sacrificial victims. They were feared throughout Mesoamerica. Historians believe the overall territory Aztecs controlled included almost twelve million people. Often, they started wars, known as the flowery wars, to obtain sacrificial victims. Religion and religious rites, including human sacrifices, were an essential part of life and society. They constructed temples, statues, buildings, or homes, all dedicated to specific gods or goddesses who controlled all aspects of Aztec life.

Codices

Much of the Aztec empire is lost to scholars today; they generally believe only about 5% of the Aztec world remains, the loss from the conquest of the Aztecs by Hérnan Cortés, one of many Spanish conquistadors. Today, we rely on primary documents sent from the Spanish conquistador and his men back to Spain; most of the known information about the Aztecs comes from Spanish chronicles and records. The authentic facts, values, and beliefs of the Aztecs were interpreted and rewritten by the Spanish. Pre-conquest or Indigenous codices, hand-written and adorned books, document the shared cultural features of the Aztecs along with other civilizations and allies of the Aztecs. It's crucial to comprehend the values and beliefs of the Aztecs to understand the consequence of Spain's arrival on art and architecture.

In Mesoamerica, the Indigenous cultures of the Maya, Mixtec, and Aztec painted pictorial manuscripts known as codices to record and preserve calendrical, genealogical, historical, ritual, geographical, and divinatory knowledge.[1]

These manuscripts also include references to the basic Mesoamerican belief system – the people needed to balance opposing forces, such as life and death. The ritualistic sacrifices helped keep the forces of their pagan gods in balance and would ensure that life would continue due to the favors that the gods would grant to the people in response to the sacrifices offered.

Scholars believe twelve to fifteen codices survived--the codices had various cultural influences in common, including glyphs used in writing, abstract artistic styles, and subjects. Though some of the techniques varied slightly, they did have different writing systems. Generally, artists who created pre-Hispanic codices, or manuscripts, focused on concept and convention over illusionism. The codices were typically made from deer hide, paper made from the Agave plant, or bark paper. The two-dimensional, conceptual manuscripts were created in the Americas while European artists created some of the tremendous illusionistic masterpieces of the European Renaissance related to the Christian religion.

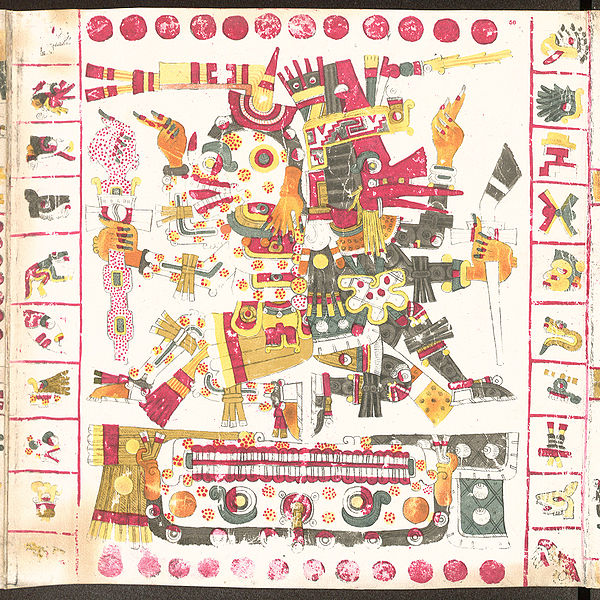

The Borgia Codex (1.7.1), which includes a page depicting the pagan deities Miclantecuhtli and Quetzalcoatl, is an example of pre-Columbian era codices. It is unclear which specific group created this codex, but there are shared stylistic features with the manuscripts produced by the Mixtec. On the page illustrated here, we see two primary deities of the Indigenous cultures – the god of life, Quetzalcoatl, is a black-masked human, who sits with its back Mictlantecuhtli, the god of death, who is shown as a white figure, like a skeleton. A depiction of the underworld, known as Mictlan, is below them (appearing like teeth or mouth of a great earth monster). Both of the gods, Miclantecuhtli and Quetzalcoatl, are vividly gesticulating. Overall, with the god of life back-to-back with the god of death, we are introduced to one of the main themes of the Indigenous cultures of Latin America – the inevitable relationship between life and death. The religious rituals and beliefs of balance between life and death are symbolized here. The symbols of the thirteen, 20-day divisions of the 260-day Mesoamerican ritual calendar are in the margins. Although most coded information is still poorly understood, historians recognize the connection between life and death and the mathematical advancements seen with dots and lines.

Once one of the greatest civilizations of the Americas, the Maya civilization was based in Yucatan at the time of Spain's arrival (Post-Classic period). The prosperity and influence of the Maya's high point date from 150 CE but declined when the Europeans arrived. Although the cause of the decline is unknown, it was probably around 900 CE when wars broke up centralized power centers into a village-based agricultural system before the Spanish arrived. It took the Spanish 170 years to establish control over the Yucatan because no single political center existed like other major Indigenous groups in the Americas.

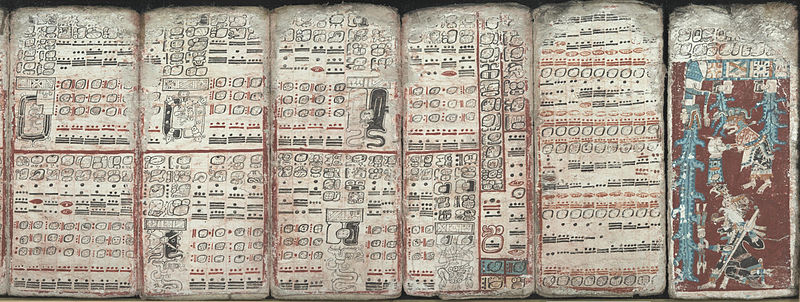

The Maya were a complex civilization and made significant achievements in astronomy and math, as demonstrated by the manuscripts, achievements closely related to their pagan religious beliefs. Maya codices include their history but also astronomical tables, religious rituals, and calendrical calculations. The Maya thought of time as cyclical, and their very complex solar and sacred calendars revolved in a cyclical format. It is believed that only three or four original Maya codices exist. Today the manuscripts are viewed from an art-historical perspective. Still, they probably functioned as utilitarian or religious at the time of their creation, especially when considering the more sacred manuscripts. These manuscripts were read by priests conducting religious ceremonies.

In the Dresden Codex (1.7.2), standard glyphs are found in the writings. Glyphs were characters in Maya writing and complex to "read." Depending on the context of the text, one glyph character can refer to several different words. Glyphs were used in connection with lines (representing the count of 5) and dots (representing the count of 1) to calculate dates and movements of celestial bodies –all tied to religious beliefs. The Dresden Codex depicts pagan gods and rituals associated with astronomical calculations to assist daily life and agriculture. When the Spanish arrived, there were 40 million people who spoke more than 1000 languages throughout the Americas. Glyphic writing may have been a valuable communication tool between the cultures in Mesoamerica that spoke several languages. The Dresden Codex also demonstrates the achievement of using zero and place notation in mathematics – familiar to the Maya. Many of these pages are highly coded, symbolic, and misunderstood today. The Dresden Codex is believed to be a copy of an original text from around 700-900 CE.

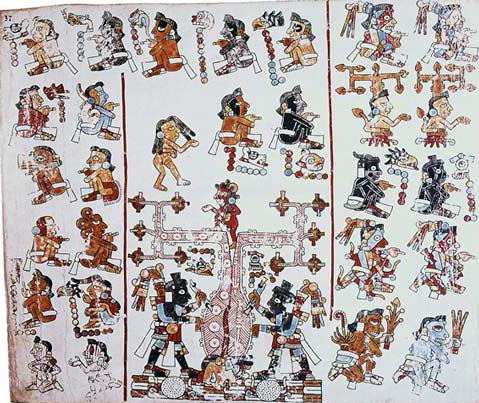

The Mixtec culture, located in southern Mexico in the current states of Oaxaca, Puebla, and Guerrero, included multiple territories with different ruling families in each region. There is evidence of a friendly relationship between the Mixtec and Aztec. Surviving manuscripts from these cultures demonstrate similarities and connections, making it difficult to ascertain precisely who the manuscript was for, Aztecs or Mixtec. Examination of the art styles reveals the manuscripts were created before the arrival of the Spanish and lacked any European influence, such as shading.

In the Codex Vindobonensis (1.7.3), the abstract style of the Indigenous cultures is present. The figures have a bold outline, are flatly painted, and are not proportionate. Images are painted on both sides of the prepared deerskin. This manuscript documents the Mixtec ruling families and the early history of the Mixtec culture; red lines help to guide the "reading" of these images from right to left. Throughout the manuscript, the dots and glyphs represent important dates of ruling figures.

The Codex Borbonicus is one of the most famous Aztec ancient manuscripts, and historians believe the codex was written before or during the Spanish invasion. The imagery was painted on bark paper and arranged accordion-style with folded pages. Today, it is 14.2 meters long. Initially, the codex contained forty pages; however, the first and last two pages are missing over time. The actual use of the codex is unknown; however, researchers suggest the book was used for astrological information and the celebrations for different periods. The Aztecs shared many of the religious beliefs of other Mesoamerican cultures, including a similar 260-day Sacred Year and a 365-day Solar Year, seen in the Codex Borbonicus. The sacred year is "a 260-day sacred almanac…in which 20 named days were paired with 13 numerals, each advancing one count per day. Within this cycle, the sequence of numerals would repeat 20 times, each of these 13-day periods constituting a trecena…"[2] (Trecena was a word used by the Spanish conquerors to define the periods in the codex.) The Solar calendar was made up of 20 named days, of 18 numerals – with five days considered bad days, added to the end to create a 365-day year.

Page 12 (1.7.4) illustrates the different days representing the trecena along the bottom and right side, each one associated with some sort of god or bird. A dot defined the number of the days, and the image portrayed the name of the day. The first-day sign is one dot and the symbol for earthquake, the second with two dots and a knife, and the third have three dots and the character for rain. The large square was illustrated with images of the deity that sponsored the trecena; on the left side is the goddess Tlazolteotl who is giving birth.

.jpg?revision=1)

Page 13 (1.7.5) is similar; in the first box is the head of a dog and one dot, the next box has two dots and the image of a monkey. The large square illustrates the deity who sponsors this trecena, Xipe Totec, and Quetzalcoatl. Priests are believed to use the twenty-six symbols to predict the future and produce horoscopes.

.jpg?revision=1)

The next section of the codex defined the order for the fifty-two-year solar year cycle, documenting the first day of each year. Today, the system is known as the calendar round. It comprises three interlocking cycles, a 365-day solar year, a cycle of 20 names, and thirteen numbers. Days are named by the way they line up. The Aztec and other groups believed nine gods controlled every ninth night, defined as the Lords of the Night. The lords determined a good or bad fortune for the night they ruled, the days in the fifty-two-year cycle based on these Lords of the Night. The final section of the codex was based on ceremonial rituals needed by the end of each cycle. This section is believed to be incomplete.

The Codex Borbonicus was made of amatl paper from the fig tree bark and used throughout Mesoamerica to create thousands of books. How the paper was made is unknown; however, historians believe they soaked the fibers before pounding them into flat sheets.

The pigments of color were made from natural materials; "wild holly root (mustard color), red juniper root and Hematite (red), yellow sweet clover (yellow), prickly pear cactus fruit (tan), and red onion skin (green) are bright and vivid, with red, green, tan, and gray predominating."[3]

After the Spanish invasion, this type of paper was forbidden; only the European-approved material was allowed. The amatl paper was an essential part of Aztec writing.

Thousands of cultural documents were destroyed by the invaders, leaving few surviving works. When the European missionaries came to Latin America, the codices were filled with information viewed paganism and devil worship. The documents were a hindrance to the conversion efforts of the Spaniards, who conducted mass manuscript burnings throughout Mesoamerica. This loss of a great deal of information is a true tragedy and part of the destruction by the Spanish conquest of Latin America. The manuscript painting did not end with the book-burning; however, the Spanish Colonial era changed subject and style significantly. After the conquest, new books were created with European influences.

Aztec Empire

Hernán Cortés arrived in the Americas in 1519, following the footsteps of many explorers before him. He landed on the eastern coast of Mexico, where he was first met by the Tabascans, a local coastal tribe. The Tabascans provided Hernán Cortés and his men with supplies, slaves, and women hoping the intrigue and wealth of the Aztecs would be more appealing to the Spanish than their territory. One of the women given to Cortés was named Malinali, later known by her Spanish name, Doña Marina. Today she is referenced as La Malinche and historically seen as a traitor – a complicated figure in history. She is notable because she understood her position, had a facility with language, and became Cortés' main translator. Surviving works of art depict her as an important figure of the conquest.

When Cortés and his men first laid eyes on the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan in November of 1519, they were amazed. The city's population was over two hundred thousand people or more- one of the largest in the world at the time! Known in English as "the Letters of Cortés," he wrote a letter to the king of Spain and said, "The city is as big as Seville or Cordoba. The main streets are extensive and very straight; some of these are on the land, but the rest and all the smaller ones are half on land, half canals where they paddle their canoes."[4] He continued to write about the riches in the city and the extensive marketplace where thousands of people came daily, selling and buying jewelry and ornaments of all kinds made from colorful feathers, shiny gold, and silver, bones, or stone. Cortés had entered Tenochtitlán, the massive Aztec city constructed by the lake. (1.7.6).

The impression the Aztec capital made on the Spaniards is further evidenced by chronicler Bernal Diaz de Castillo, who wrote, "When we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land we were amazed and said it was like the enchantments . . . on account of the great towers and cues and buildings rising from the water, and all built of masonry. And some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream? . . . I do not know how to describe it, seeing things as we did that had never been heard of or seen before, not even dreamed about."[5]

Aztec art was based on the multiple artistic civilizations that preceded them, including making incredible stone sculptures, monumental architecture, and art related to the people, environment, and deities, frequently fashioned into abstract images. The Aztecs were masters of gold objects with few artifacts surviving the Spanish invasion. In an infamous quote by Cortés, he boasted that his men "suffer a disease of the heart that can only be cured with gold." Most of the small gold and silver metal works sculptures were melted down to fund the Spanish for various Christian conquests. Artifacts of stone sculpture and architecture were found documenting the Aztec beliefs and a wide variety of deities. Art was used reinforcing status, power, and religious beliefs, conveying the stories of the culture. Notably, many of the works of art reflect the values and beliefs of the Aztecs, especially the need for sacrifice.

.jpg?revision=1) Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Painting of Tenochtitlan on Lake Texcoco - CC BY 1.0 by Gary Todd

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Painting of Tenochtitlan on Lake Texcoco - CC BY 1.0 by Gary Todd

Aztec Architecture

The Templo Mayor (1.7.7) was the heart of the capital city of Tenochtitlán. The Templo Mayor consisted of two temples on top of a pyramidal base (the pyramid base does not come to a point). One temple was dedicated to the God Tlaloc, associated with rain, and God Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun. During the rainy season, the sun rose behind Tlaloc's temple, and during the dry season, the sun rose behind the temple of Huitzilopochtli. The most important rituals took place in Templo Mayor, including naming their leaders and religious ceremonies. A total of seven building phases were discovered incorporating temples built over previous temples, or an expanded façade, eventually ending with the most prominent, seventh temple. As the Aztec Empire increased, so did the expansion of the Templo Mayor. In each addition, captives from subjugated tribes could be sacrificed. The version seen by the Spaniards rose 39.6 meters in height, and the higher a person or a sacrificial victim climbed to the top of the pyramidal structure, the steeper the slope became. This change in slope partly enhanced the sense of awe people had when they reached the top and made sacrificial victims dizzy as they were brought to be sacrificed. The victims were also starved and drugged to subdue them in their final hours.

Because of the connection with religious rituals and sacrifice, and in his quest to Christianize the Aztecs, Hernán Cortés destroyed the Aztec city. They built what is now Mexico City – literally on top of the old Aztec capital. In the 1970s, authorities were repaving streets in Mexico City and discovered the Templo Mayor's ruins (1.7.8). Today, the top of the pyramidal base is visible, with temples of Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli (covered by the green roof in the background).

The Templo Mayor was only one of many structures that made up the spiritual center of the city. Other vital buildings included temples to other deities, like Quetzalcoatl, and a ball court. The ball courts held a unique ball game played by indigenous cultures of Mesoamerica, each with a different format and rules. Sometimes those who won the ballgame were sacrificed and viewed as an honor, or those who lost were sacrificed. Which group was officially sacrificed is unclear because several diverse civilizations played different forms of the game. Although the ball court no longer survives in the Aztec capital, they are found in other Mesoamerican areas not as dominated by the Spaniards, for example, in the Mayan city of Chichen Itza (1.7.9). Skull racks often were placed near ball courts. Known as tzompantli, they displayed the skulls of sacrificial victims. Although it is an uncomfortable truth, the remains of sacrificial offerings are well documented in the second largest temple of the Aztec capital region, Tlateloco, and in the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City.

The excavated House of the Eagles also has evidence of sacrifice, not only in blood found in the temple but also in the artwork portraying Eagle warriors' self-sacrifice. Merging sculpture and architecture, the carved bas-relief banquets (1.7.10) depict armed warriors on either side of what represents a ball of dried moss or grass to hold the bloody spikes used in self-sacrifice.

Aztec Sculpture

Making stone sculptures was a tradition in Mesoamerican cultures, carving multiple materials found in local areas. The Aztecs continued with the stone sculptures making thousands of different statues, small personal items, or monumental temple works. Although the Spanish tried to demolish most of the sculptures when they invaded, many still survived. Images and sculptures of religious deities, made for personal use or religious ceremonies, formed the most significant number. The sculptors had to follow specific standards for the deities, which were very symmetrical in a frontal position. "Females are frequently kneeling, their hands resting on their knees, while male figures are often sitting with their knees drawn up and their arms crossed upon them. Ageless faces – inlaid eyes and half-open mouths lend them a lifelike look…"[6] On the primary image, sculptors added features from animals, ornaments, headdresses, or other decorations. The artists only had stone and wooden tools for carving with sand and water to help smooth the stone.

When different areas were excavated, they found beautiful works of art between buildings, some probably never seen by Hernán Cortés or his men. For example, in stage three, eight sculptures were found in a row (1.7.11), leaning against a staircase (three reproductions are shown in the image). Historians believe the sculptures represent the stars, siblings of Huitzilopochtli and Coyolxauhqui, and sons of Coatlicue.

The sculpture of Coatlicue (1.7.12), a Nauhatl word meaning "She of the Serpent Skirt," is one of the more famous surviving works, standing at an imposing almost three meters tall. The statue leans forward with her arms pulled in. Snakes from her skirt, belt, and head and seem to slither across the figure. She is wearing a huge necklace depicting a skull, hands, and hearts. Beneath her necklace is two flaccid breasts, a symbol of motherhood. Two enormous snakes curl upwards from her severed head to face one another. Their bifurcated, or split, tongues curl downwards; the resulting effect of the snakeheads and tongues appear to be a single, forward-facing serpent face. As we see here, snakes coming out of body parts was an Aztec convention for squirting blood. Coatlicue was decapitated, and her snaky head represents the blood squirting from her severed neck. There is a rhythm of circular shapes around her neck where her head was cut off. Her arms are also formed of snakeheads, suggesting she was dismembered there as well.[7]

Coatlicue is a potent visual expression of the Aztec beliefs; legends say she was a guardian princess of a shrine. While cleaning the shrine, Coatlicue miraculously became pregnant with Huitzilopochtli. To restore the honor of the family, her 400 sons and one daughter (Coyolxauqui) banded together to kill her. Once her head was cut off and the two serpents emerged, Huitzilopochtli leaped forth and avenged his mother's death by chasing away his brothers and dismembering the body of his sister, Coyolxauhqui. He threw her head to the sky so his mother could remember her daughter – now known as the moon goddess--and threw the rest of her body down the temple stairs. Originally painted and sculpted on all sides, this image would have captivated those who worshiped the statue. Drawings completed in the early nineteenth century show a figure carved in low relief at the sculpture's base (1.7.13), seen in the reproduction. Historians believe the crouching figure carved on the bottom is an image of the earth deity and perhaps is a portal to the underworld.

A large stone disc, found between building stages of the Templo Mayor, represents Coyolxauhqui (1.7.14), an Aztec Nahuatl word for "She of the Golden Bells." Based on the specific ritual, historians believe sacrificial victims' bodies were thrown down the temple's steps and would land on this gruesome disc of the dismembered Aztec goddess. The Coyolxauqui stone is one of the few original large-scale Aztec sculptures perfectly capturing the Aztec view of their deities, a dismembered body, and representations of skulls. Coyolxauqui's depiction, along with Coatlicue, demonstrates the awesomeness and fear Aztecs felt toward their deities. Although these works of art are sculptures, they are in bi-level relief, enhancing the two-dimensional effect viewed in indigenous manuscripts. Although Hernán Cortés probably never laid eyes on the sculpture of Coyolxauhqui, he did bury Coatlicue after the statue's discovery. The large sculpture of Coatlicue has been subsequently buried, unburied, and reburied several times. Today, both works of art are displayed in Mexico City.

.jpg?revision=1)

One of the most well-known Aztec sculptures is the Sun Stone (1.7.15) and was initially discovered near the Templo Mayor in 1790. The Sun Stone is a stone carved into a solar disk to represent the myth of five suns – four suns of the universe imperfectly made seen in the squares around the central circle, and the fifth sun, seen in the center disc, in which the Aztecs existed. The center face is shaped like an obsidian blade as a tongue – a reference to the need for human sacrifice for the sun to rise. The claws on either side of the face do not belong to the sun and represent the hearts offered to the sun; framing the face is the symbol of Ollin (movement). The boxes correspond to previous suns: 4-tiger, 4-wind, 4-rain, and 4-water; the previous worlds were destroyed based on these symbols (wind, rain, etc.). According to legend, earthquakes (movement) will destroy the world of the fifth sun. Some historians are not sure which world is in the center and might be either the day sun, the night sun, or the earth monster. Two jaguar heads and two serpents' heads move outward, while the next band around the center represents the 20 names for the days surrounded by fire serpents. The glyph at the very top represents the date 13-Reed (1427), the date of the fifth sun. It is unknown whether the stone was a tribute to a god or perhaps a sacrificial altar.

Small Carved Aztec Statues:

Maize and chocolate were two of the important plants used by the Aztecs, most notably in religious rituals and frequently reflected in their sculptures, along with other food items. The man (1.7.16) holding the oversized cacao pod is a stone sculpture representing one of the merchants transporting the cacao from the lowlands to the valley. Merchants were frequently part of a higher status and demonstrated economic power. Drinking chocolate made from cacao was a privilege enjoyed by the elites, warriors, merchants, priests, and nobles. It was noted, "The common folk, the needy did not drink it."[8] The statue was made from a volcanic stone with some red and white pigment remains, indicating the sculpture was painted.

Dogs were significant to Mesoamericans and were companions to humans as well as a source of protein. Xolotl (1.7.17) was the god who was associated with lightning and death. He was frequently depicted with a dog's head, the canine brother of Quetzalcoatl, and protector of the sun from the underworld. Dog sculptures were often found in burials to help their owners cross the river of the underworld. Frequently, the eye sockets are empty; legends believe he cried so much the eyes fell from their sockets. His ears are generally ragged, and his teeth symbolize fangs.

Xiuhcoatl (1.7.18) was the mythological serpent, a fire deity, and a common representation in Aztec art. The serpent is shown with a curved snout, short legs with claws. The segmented body has a tail shaped into a triangle representing the solar rays and two trapezes the symbol for a year. The sculpture was probably part of a temple façade.

The Chacmool (1.7.19) is a sculptural form always made in the same position; the form is reclining, the head turned towards the front, elbows supporting the figure, and a bowl sitting on the chest. This Chacmool was found in the Great Temple, associated with the rain god. The bowl was used to place sacrificial items from feathers to food to human hearts. Carved from stone, some of the original paint remains on the figure. He is staring straight ahead, mouth open to expose his teeth, anticipating the sacrifice. Shared cultural features exist among various groups of Mesoamerica, and Chacmool sculptures were also found in Maya territories.

This female sculpture appears seated and wearing a simple skirt and belt. The detailed face with its huge eyes, exposed teeth, disheveled hair, and clawed hands demonstrate the potential fierceness of the demon. The Cihuateteo (1.7.20) came to earth on five specific days, haunting places associated with evil and escorting the sun each day as it traveled through the underworld before dawn. If a woman died in childbirth, her soul became one of these demons. This type of figure was found throughout Mesoamerica.

Chicomecoat (1.7.21) was a goddess responsible for the viability of corn and other edible crops. Wearing a long skirt, she holds ears of maize in one hand, with a large headdress. The headdress has a quadrangular shape and was called the amacalli or paper house. This type of adornment was common for a corn goddess, and during celebrations, representations of the headdress were made from bark and worn by celebrants. The statue was made from a flat stone slab, retaining the angular shape except for the rounded face peering out of the middle.

Aztec Featherwork

Featherwork was one of the most prestigious art forms. The amantecas (feather artists) were the most respected, well-paid artists and considered upper class. The amantecas formed into guilds and worked for the rulers, priests, and elites of the empire. The workers used multiple methods to work with the feathers and attach them, including sewing, wrapping with agave cord, and a form of glue or crimping. The mosaic technique was used for shields, clothing, or flat surfaces using fragments of feathers, the lesser quality of feather on the first layer, and the prized feathers for the top.

Birds were raised in aviaries, or the feathers had to be imported. Colorful birds lived naturally in the area, and the brighter the feather, the more value it carried. Macaw feathers were highly desired with bright red, blue, yellow, or green colors, but the Quetzal was the most treasured, producing vibrant green or blue colored feathers. Some documentation told stories of Moctezuma II carried by servants on a litter decorated with brilliant quetzal feathers and string of gold tassels to meet Cortés. In the Letters of Cortés, he writes to the king of Spain about the magnificent aviary of Moctezuma II and the spectacular featherworks.

The shield (1.7.22) with the pattern of meander and sun was a common theme. The design was a 'step fret' and resembles the Greek key design. Although historians do not know the actual meaning of the image, Aztecs used the method on everything; shields, clothing, sculptures, murals, and ceramics. The design was usually replicated several times; however, there is only one iteration on the shield. The shield was covered in feathers from less colorful birds, probably made for a lower-level warrior.

The most well-known surviving artifact is the Moctezuma headdress (1.7.23), although historians are not sure he or a surviving example wore it. The headdress had over 400 tail feathers from the Quetzal and other feathers from the Cotinga, Spoonbill, and Cuckoo, all attached to a net of fibers. The front was adorned with gold, including a bird's beak made of gold; unfortunately, it was lost.

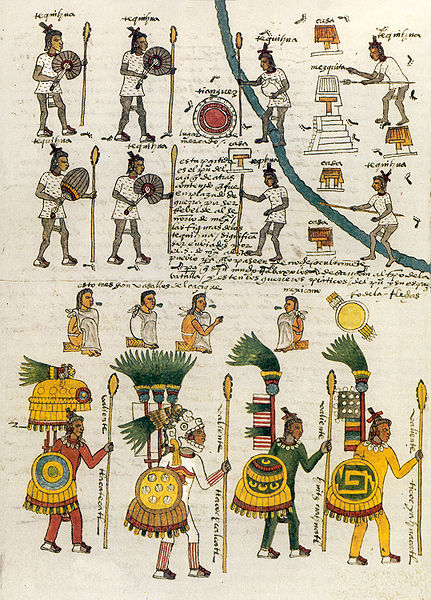

A post-conquest page from the Codex Mendoza (1.7.24) illustrates feathers in the ornamentation of warriors' gear. Elaborate shields, headdresses, and banners were decorated with feathers as the warriors' scout a town in preparation for an attack. The high-ranking commanders on the bottom wear the most elaborate featherwork.

Gold

Gold was a significant metal for the Aztecs, who made thousands of pieces out of gold; unfortunately, gold was also one of the reasons for the invasion of the Europeans into Mesoamerica. The invaders took almost all of the Aztec gold art, melted it into ingots for easy transportation, and shipped them back to Europe. "Gold, in Aztec belief, was teocuitlatl, a godly excrement, closely associated with the sun's power, and ornaments made of it were worn by Aztec rulers and nobles."[9] The labret (1.7.25) was a plug made to be inserted into a hole pierced in the lower lip. The serpent has serrated teeth and fangs and a prominent nose. The oversized tongue was made to move back and forth as the person moved, adding to the snake's power. On the back of the plug is a flange that held the plug in the person's mouth. The labret was worn by an important noble or warrior, illustrating the importance of the person. Using a lost-wax method, the labret was made with melted metal in a mold and the finished gold highly polished.

The gold necklace (1.7.26) has thirty-four beads formed like the molars of a jaguar and thirty-four small bells. The beads were made with the lost-wax method, the bells attached with a filigree. The necklace was found in a tomb along with actual jaguar teeth, demonstrating the respect the Aztecs had for this animal with its powerful jaws, able to pierce through the skull of its prey with one bite. The jaguar warriors were the elite, wearing pelts and headgear resembling the jaguar. Someone of high status and importance wore this necklace.

Multiple animals were used as inspirations for necklaces, including the frogs, who were associated with fertility, water, and rain. Using the lost-wax method, each small frog (1.7.27) was made in a clay mold with slight differences in each figure. When the Spanish came to Mesoamerica, they were offered many of the exquisite ornaments of gold; however, the Spanish were only interested in melting the gold into ingots. Most of the surviving gold works were found in hidden places or undiscovered tombs.

Black-on-orange Pottery

The skill and methods to make pottery was passed through the potters, defining the clay recipes, how vessels were fired, or the shape of a bowl or pot. Different types of clay were plentiful in the lakes, and the recipe for pottery usually mixed one kind of clay with a sandier form to aid in its stability. They did not use a potter's wheel and formed clay by hand or in molds. Most of the vessels were made for cooking or eating, the earlier forms rounded as in the distinctive ollas used over fires to cook beans or maize. Generally, not covered with slip, the pottery was fired in updraft kilns or open-pit kilns, both using low temperatures.

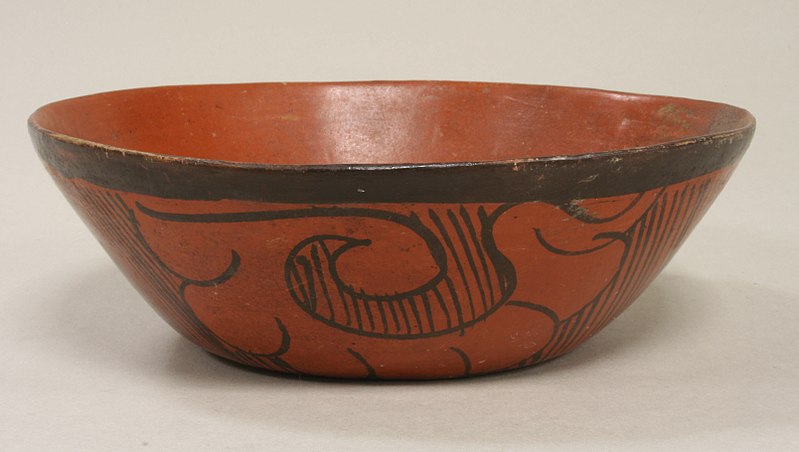

The Aztec made decorative pottery; some covered with a simple red slip to polychrome ware covered with a white or orange-colored slip and painted with black, brown, red, or orange designs. The most well-known was the 'black on orange,' which had an orange slip and then painted with decorations in black. The simple bowl (1.7.28) was probably made for everyday use and painted with a scroll design on the sides.

The plate (1.7.29) was covered in orange slip and then painted with a black and white design of the nagual – the human who can transform into an animal form, and on this plate, it takes the form of a coyote. Decorated ceramics were used in Aztec culture as serving dishes at festivals and ordinary meals. The presence of Black-on-orange ceramics at Late Aztec sites ranging from the smallest communities to Tenochtitlan indicates that Black-on-orange pottery was not exclusively for high-status households but rather was available to commoners as well as to cities.[10]

Large numbers of animal-shaped vessels were found throughout the area, usually used for ceremonial purposes. The animals represented some part of the cultural beliefs and were associated with cosmic definitions. Birds represented the celestial realm, messengers between those on earth, and astrological events. The bird on the tripod vessel (1.7.30) is covered with shiny red, black, and matte feet. Supporting legs and tail represented the king vulture.

Although king vultures feed primarily on carrion, they will occasionally kill for food; they are therefore connected with human sacrifice in ancient Mexican thought. The rendering of the bird includes three significant human aspects: from its projecting "ear" flanges hang pendant ornaments; its talons are shown as hands with prominent thumbs; and its head is adorned with a pleated paper fan often seen on headdresses of Aztec deity figures. The contours of the vessel are well-balanced—the lines of the sloping wings echoing the angles of the legs—and the bulging chest of the bird is perfectly centered between its strong legs. [11]

Figure \(\PageIndex{30}\): Condor vessel (Ceramic) CC BY-SA 2.0

Figure \(\PageIndex{30}\): Condor vessel (Ceramic) CC BY-SA 2.0

Much Aztec art was lost, destroyed, or buried; fortunately, the artifacts buried in tombs or under buildings are the survivors of the period. Much of Mexico City covers the great Templo Mayor, a major part of the city of Tenochtitlan. Today, the area around the Templo Mayor and many other areas in Mesoamerica are under excavation, and further study by archaeologist may lead us to have an even greater understanding of the magnificent cultures of the beautiful cultures Mesoamerica.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.lib.uci.edu/sites/all/ex...so/sacred.html "Realms of the Sacred in Daily Life: Early Written Records of Mesoamerica." Realms of the Sacred in Daily Life: Early Written Records of Mesoamerica. The Regents of the University of California, 2009. Web. 1

[2] Pool, C., Kidder, B., UKnowledge, A Glimpse into Ancient Mexico: Writings of the Aztecs, Mixtec and Maya. Retrieved from https://uknowledge.uky.edu/world_mexico_codices/9/.

[3] Retrieved from http://mati.eas.asu.edu/chicanarte/html_pages/CodexIssOutl.html.

[4] Retrieved from https://www.livescience.com/34660-tenochtitlan.html

(From “An Age of Voyages: 1350-1699,” by Mary Wiesner-Hanks, Oxford University Press, 2005).

[5] Retrieved from: https://www.oercommons.org/coursewar...tudent/?task=4

[6] King, Heidi. “Aztec Stone Sculpture.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/azss/hd_azss.htm (October 2003)

[7] Retrieved from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-americas/early-cultures/aztec-mexica/a/coatlicue.

[8] Moran, E., (2016). Sacred Consumption: Food and Ritual in Aztec Art and Culture, University of Texas Press, p. 45.

[9] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/321343?searchField=All&sortBy=relevance&ft=aztec+gold&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=10.

[10] Hodge, M.G., Hector N., Blackman, M. J., Minc, L. D., Latin American Antiquity, Black-on-Orange Ceramic Production in the Aztec Empire’s Heartland, June, 1993, 4(2), p. 134.

[11] Retrieved from. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/314365?searchField=All&sortBy=relevance&ft=aztec+ceramic&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=5.